The Crimean War

This, the most destructive of the Victorian era, was notable for the appalling suffering of the troops, the outmoded and inefficient military organisation and the recognition at last of the courage of all ranks of soldiers and sailors with the instigation of the Victoria Cross.

It is remembered for the unreasoning courage of the Charge of the Light Brigade, for the precise volleys of the Thin Red Line and for the impossible assaults upon Sevastopol’s Redan.

It also demonstrated the inefficiency and ineffectiveness of the British military system based on privilege and purchase.

Although Russia is a very large country with plenty of sea coast it has no entrance to the Mediterranean Sea from the Black Sea and this has always been a sore point with her. Barring her way is Turkey and during the middle of the last century, Russia was very intent on picking a quarrel with Turkey, so that she could capture some territory of gain some concessions which would secure her free passage for her fleets through the Bosporus and Dardanelles into the Mediterranean Sea. The opportunity for quarrelling with Turkey came in 1853 when the monks of the Greek and Latin Churches in Palestine quarrelled amongst themselves regarding which church should enjoy privileges in Jerusalem and Bethlehem.

It so happened that the Czar of Russia was the head of the Greek Church as he naturally supported their view, while on the other hand, the Emperor of France supported the Latin Church. England had no wish to see Turkey crushed and Russian ships enjoying free passage into the Eastern end of the Mediterranean and she consequently joined France when Russia threatened Turkey. On 27th February 1854, France and England declared war on Russia.

Five large sailing transports, the Echunga, the Medora, the Shooting Star, the Mary Anne and one other were provided to transport the 8th Hussars. The Echunga, the Mary Anne and the Shooting Star sailed from Plymouth between the 19th and 27th of April, 1854 and all three arrived at Constantinople on the 20th of May.

At Constantinople, the men were disembarked under Major de Sallis at Koulouli Barracks three miles north of Scutari on the Asiatic side, where they found the 17th Lancers, who had sailed from Southampton a few days before. The disembarkation was hardly completed before secret orders were given to prepare to reembark for the expedition to Varna to assist the Turks, then hard pressed by the Russians on the Danube. Accordingly, the three ships with the men under de Sallis were towed by steamers up the Bosporus and arrived at Varna on the 31st of May, and disembarked, encamping on the north of Varna Lake, about a mile from the town.

On the 6th of June Sir George Brown with his Light Division advanced from Varna to Aladyn, with the 8th forming the advance guard. It was sent on the same day to Devna about 16 miles west of Varna with orders to patrol the country north and west of the place in which they were, along with a Turkish cavalry regiment.

In the meantime the other two ships with the Head Quarters and the remainder of the regiment sailed from Plymouth around the 1st of May and without stopping disembarked at Varna on the 10th of June, arriving at Devna Camp on the 17th.

Lord Cardigan joined at Devna in June, and soon afterwards the rest of the Light Brigade arrived.

For thirty-eight days the Russians attacked Silistria, and the Turks stubbornly defended it. On the 25th of June, a squadron of the 8th and 80 men of the 13th Light Dragoons, accompanied by Lord Cardigan reached the Danube near Trajan’s Wall and then turned west to Silistria, not meeting any Russians on this side of the river. From Silistria they returned via Shumla to Devna. Similar patrols and reconnaissances were the order of the day.

Lord Cardigan drove his men at a punishing pace, and when the patrol returned the men and mounts were in terrible condition. Fanny Duberly, the wife of the 8th Hussars Paymaster, saw them as they straggled back to camp on the 1st of July:

“The reconnaissance under Lord Cardigan came in this morning, at eight, having marched all night. They have … lived for five days on water and salt pork; have five shot horses, which dropped from exhaustion on the road, brought back a cart full of disabled men, and seventy-five horses which will be unfit for work for many months, and some of them will never work again. I was out riding in the evening when the stragglers came in; and a piteous sight sight it was, men on foot driving and goading the wretched, wretched horses, three or four of which could hardly stir. There seems to have been much unnecessary suffering, a cruel parade of death.”

Lord Cardigan, along with his staff, half the 17th Lancers, and four-fifths of the 8th embarked for Crimea on the 31st of August. Sickness had left officers, men and horses in a weakly condition. On the 16th of September, all of the 8th landed.

In the three and a half months since the 8th’s arrival in the East 95 men were non-effective or dead at the time of disembarkation in the Crimea.

Alma 20th September 1854

During the second week in September, the allied forces (i.e British, French and Turks) landed at Eupatoria, which is about 30 miles north of Sevastopol.

The army at this time was suffering a good deal from cholera and an almost complete lack of transport. When the Russians learned of this landing they took up a position along the Southside of the river Alma, which runs into the Black Sea about midway between Sevastopol and Eupatoria. On the 19th of September, the allies moved south to oppose them.

The whole of the cavalry, which was under command of Lord Lucan, was organised into two brigades, the Heavy and the Light. The famous Light Brigade was under the command of Lord Cardigan and was composed of two squadrons from each of the following regiments: – 4th Light Dragoons, 8th Hussars, 13th Light Dragoons, 11th Hussars and 17th Lancers.

The allies reached the Alma on the 19th of September, drove back the Russian’s outposts, and the next day the battle began in earnest.

The battle was very largely combated between the opposing guns and infantry, and the cavalry on both sides had little to do but watch each other. The 8th Hussars recorded no casualties during the battle of the Alma.

The battle opened with the infantry attacking an entrenched position of the Russians and capturing it, but the Russians counter-attacked and owing to a mistake in the British ranks by someone shouting ‘retreat’ which was taken up all along the line, we lost the position. As soon as the mistake was realised the British again advanced and the Russians were driven from the field back into Sevastopol with great loss.

Balaklava 25th October 1854

After their victory of the Alma, the allied army moved overland by the east of Sevastopol to the South port, intending to attack from that side. The British base was established at Balaklava, which is on the sea coast about nine miles South of Sevastopol. In addition to the casualties suffered at the Alma, the armies were being reduced in strength by cholera.

To prevent the allied fleet from entering the Sevastopol River the Russians sank a number of ships across the month. This was a good move on the part of the Russian Commander because it enabled him to take the army out of the town in a North-Easterly direction and thus threaten the allied army from the East, whilst leaving the defence of the port to the seamen, who left their ships and manned the fortifications.

Measures were soon taken to capture the port and the French and English guns bombarded the place to good effect. The French however were unfortunate in that some Russian shells hit their power magazines and exploded them. Although a great deal of damage was not done it had a bad effect on the French troops, who would not take their part in an assault that had been arranged.

Later on, however, another bombardment had to be arranged because the Russians worked very hard and repaired most of the damage to their works as soon as they saw an opportunity to do so. But once again the French were unfortunate and the assault was again postponed.

This was most annoying to the British because our gunners had made excellent practice and had battered down the fortifications in a number of places.

During these siege operations, the cavalry was encamped near Balaklava.

On the 24th of October 1854, a strong Russian force of all arms was observed at a place called Tchorgun, about five miles, North-East of Balaklava and seven miles South-East of Sevastopol. It was thus in the rear of the British infantry and guns carrying on the siege. The object of this Russian force was to destroy the British base at Balaklava.

Before dawn the next morning the British cavalry were standing on their horses and Lord Lucan and his staff rode out to watch the enemy. The Russians however had made a very early move and were nearly halfway to Balaklava when Lucan saw them. He rode back at once and gave the order to mount and took up position to the westward, thus threatening the Russian right flank should it continue its march on Balaklava. The Russians were greatly superior to the British in number by about ten to one.

Lord Raglan the British Commander-in-Chief was watching operations from a high plateau to the West of the Russians and he ordered Lord Lucan to withdraw the cavalry to the foot of the plateau until the situation became a little clearer. At the same time, two infantry regiments taking part in the siege of Sevastopol were ordered to go to support the cavalry.

Presently for some unknown reason, the Russian cavalry commander halted his force and Lord Lucan seizing the opportunity sent the Heavy Brigade under General Scarlett, at it. The Russians were over 3,000 strong while the Heavy Brigade was only about 800, yet Scarlett’s weak squadrons crashed into this great mass of the enemy and eventually drove it off the field and pursued it until checked by our own officers.

The Russian Commander now concentrated his men, who still greatly outnumbered the British and posted 12 guns and his cavalry at the East end of a little valley and some of his force on both sides. At the West end of the valley stood the Light Brigade.

During a lull in the operations, Lord Raglan noticed that Russian artillery teams were moving forward to remove the guns they had had to abandon during the earlier fighting. He, therefore, sent an order to Lord Lucan by Captain Nolan of the 15th Hussars directing the cavalry to advance rapidly to the front and prevent the removal of the guns. Lord Lucan unfortunately was on low ground and could not see the Russian teams and quarrelled with Captain Nolan about the order.

Growing impatient, Lord Lucan asked Captain Nolan what he was expected to do, whereupon the latter in a fit of temper waved his hand eastward and said ‘There, my lord, is your enemy and there are your guns’ and rode away. Lord Lucan said no more but rode over to the Light Brigade and passed the order on to Lord Cardigan, who understood it to mean that there were Russians at the other end of the valley which he was to attack and that they had guns on each side.

The Light Brigade moved off at a trot in three lines in the first was the 13th Light Dragoons and 17th Lancers: in the second only the 11th Hussars and in the third the 4th Light Dragoons on the right and the 8th Hussars on the left.

The Brigade had hardly gone a hundred yards when Captain Nolan galloped back across its front waving his arm and shouting furiously as if to make the brigade change direction half-right, what he intended to convey will never be known for he was struck dead a later by a fragment of shell.

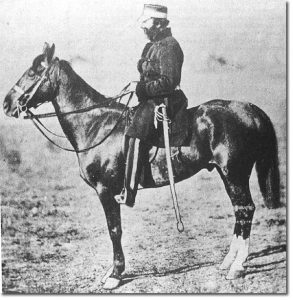

Colonel Shewell, 8th Hussars

The Brigade continued its advance down the valley in beautiful order until the Russian batteries and riflemen opened fire upon it and then officers and men fell fast. The advance quickened then but, with perfect discipline, order and dressing were kept although riderless horses created some confusion. The twelve Russian guns blew the leading ranks to pieces, but with a terrific charge, the remainder of the Light Brigade was upon the gunners and sobered them.

Each regiment fought some Russian formation, the 8th Hussars passed the remains of the battery in the valley and halted about 300 or 400 yards beyond.

They had passed completely through the crossfire between the infantry and the batteries on the hills, losing about half their men. They were so diminished in numbers that they now formed only one squadron. Gradually a few joined the remnant of the 8th, and when the regiment formed up there were about fifteen chiefly of the 17th, who formed on the left, making in all about seventy men.

The 8th Hussars, under the command of Colonel Shewell, wheeled about and then charged two squadrons of Russian Lancers. The ground was now opened for the Brigade to retire. The British gradually withdrew to their former positions and the action came to an end, during which the gallant Light Brigade had suffered terrible losses.

Private John Doyle, of the 8th Hussars, was fortunate to survive the charge:

“My horse got a bullet through his nose, above the noseband, which caused him to lose a great deal of blood, and every time he gave his head a chuck the blood spurted over me. That night when I opened my cloak, I found 23 bullets in it. There were five buttons blown off my dress jacket, the sling of my sabretache were cut off … I also had the right heel and spur blown off my boot.”

The casualty roll of the 8th Hussars can be viewed here.

Why not discover a direct insight into events on this battlefield through the eyes of an anonymous troop sergeant major, in a letter he sent home to his father.

With the charge of the Light Brigade at Balaklava, the work of the cavalry in the Crimean War practically came to an end.

However, the suffering of the Light Brigade veterans did not end on the 25th of October, 1854. Why not discover what fate awaited those who returned from the war.

Inkerman 5th November 1854

On 28 October Lord Raglan ordered the cavalry to move their camp to Inkerman Heights. The heights were exposed to the cold winds which blew across the Crimean Peninsula and offered little shelter from the elements or firewood for cooking fires.

Under the cover of dense fog at dawn on the 5th of November 1854 around 60,000 Russian troops attacked the British position on the Inkerman Heights and simultaneously a further 40,000 sailed from Sebastopol to attack the French siege works.

The Light Brigade was ordered to mount and ‘stand ready’ just behind the front line in case they were needed under the command of Lord George Paget. It was at this time the Light Brigade moved forward and supported some squadrons of French Chasseurs d’ Afrique which enabled them to achieve their objectives.

The Siege of Sevastopol lasted well into the autumn of 1855 and at last, peace was proclaimed.

Gallantry Awards

- 453 Sgt M Clark DCM

- 931 Cpl P Dunn DCM

- 1153 Pte W Fulton DCM

- 934 Pte R Moneypenny DCM

- 1185 Cpl J Neal DCM

- 1078 Pte T Twamley DCM

- 855 Pte J Whitechurch DCM

- 420 RSM S Williams DCM

Battle Honours

Campaign Medal

The Crimea Medal was a campaign medal that was established on the 15th of December 1854 for award to British units of land and Navy (and some French Forces) that took part in the campaign against the Russians on the Crimean peninsula and the surrounding waters from 28th March 1854 to 30th March 1856.

The Crimea Medal was a campaign medal that was established on the 15th of December 1854 for award to British units of land and Navy (and some French Forces) that took part in the campaign against the Russians on the Crimean peninsula and the surrounding waters from 28th March 1854 to 30th March 1856.

The medal was awarded the British version of the Turkish Crimean War medal, but when a consignment of these was lost at sea some troops were issued with the Sardinian version instead.

The medals were originally issued unnamed but could be returned for naming free of charge. Those which were officially named were done in indented square or engraved capitals.

The ‘Azoff’ clasp was only issued to Naval and Marine personnel who served in the Sea of Azoff. The maximum number of clasps awarded to any one individual was four. The oak leaf and acorn pattern of the bar are unique to this medal. The correct order of wearing the clasps is in date order from the bottom upwards.

Medal Clasps:

- Alma

- Balaklava

- Inkerman

- Sebastopol

- Azoff