By Lieutenant General Sir Robin Macdonald Carnegie KCB OBE DL

In March 2000 Mr D. Dickerson loaned his father’s medals to the Queen’s Own Hussars Museum in Warwick. The group consisted of the: British War Medal 1914-20, Victory Medal 1914-18, General Service Medal 1918-62 with clasp ‘S. Persia’ Defence Medal, Long Service and Good Conduct Medal (George V), and the Meritorious Service Medal (George V) of which the rarest and most interesting is the General Service Medal 1914-18 with the clasp ‘S. Persia’.

Throughout the 19th Century and the early part of the 20th, the Russian and the British Empires viewed with suspicion each other’s extension of power over the arc running from Constantinople to Lhasa.

Persia was at the centre of this arc. In the British Empire, the struggle was known as “The Great Game”, but for some of the players it was a game ending in torture and death. In 1907, after major internal disorder and continuing rivalry between Russia and Britain, the Anglo-Russian Convention was signed, by which Russia acquired a sphere of influence in the North of the country while Britain acquired a similar one in the South.

In between there was a central area that was open to trade by both countries. In 1914 Persia declared its neutrality in the 1914-18 War, but by the end of 1915, the increasing German penetration posed a threat to both Russia and Britain.

The situation, however, became even more unstable with the revolution in Russia. Into this vacuum moved the Bolsheviks in the North and the British in the South. In 1916, to control a fierce tribal uprising, Brigadier General Sir Percy Sykes was ordered to raise an 11,000 British-officered native force, ‘The South Persia Rifles (SPR)’. Their base was at Shiraz in Southern Persia – now, Iran.

On the Gulf coast, this force was reinforced by two regiments from the Indian Army, one of which was The 16th Rajputs. The SPR had a record of mutinies and desertions but was disbanded finally for political reasons in late 1919.

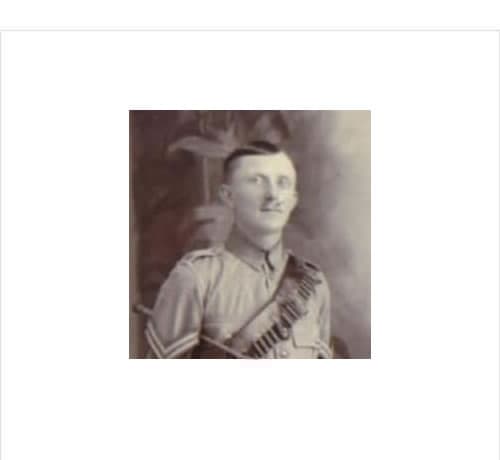

In June 1907 Dickerson enlisted in the Army and by 1916 was a Sergeant in the 7th Hussars who were stationed in Meerut, India. He was a qualified instructor in musketry and the machine gun. In January 1917 he was seconded to the SPR as the British N.C.O. instructor in the 2nd Machine Gun Squadron of the Kerman Brigade.

In September 1921 his brigade commander, under whose command he had been for the previous two years, wrote: ‘ ….. since March 1921 he has been practically in command without any British officer. I consider that the M.G.sqdn of this brigade is one of the best “shows” in the SPR and this is undoubtedly due to the unsparing efforts of this N.C.O. He has maintained a very high order of discipline among the Persians under him and at the same time has always commanded great affection and respect from Persian officers and men’.

The brigade commander continues: ‘During the three years with the S.P.R., I have held a very high opinion of the NCOs sent to the force by the 7th Hussars and I put Dickerson easily at the top of this list and I have kept him with me till the very last & his influence and knowledge of the Persian officers & men have been of great assistance to me in the difficult task of peacefully disbanding this force.

In another letter to a squadron leader in the 7th Hussars, he wrote: ‘We have had a ticklish time here lately & Dickerson has been of more use to me than some of the British officers’.

To bring colour to these somewhat prosaic reports, some incidents involving the Editor’s father, then a young officer in the 16th Rajputs, are included.

THE RAJPUT ACCOUNT

My father, Lt Col (Retd) George Miller came from a family of Calcutta Scots “Box Wallahs” (that is British Businessmen trading in Bengal) who first arrived in India in about 1760. He was born in 1897 and was commissioned into the 16 Rajputs in 1916. Initially, he was sent to join a force being assembled in Basra for the relief of Kut then under siege by the Turks. He never reached Kut because General Sir Charles Townsend, commanding the Anglo-Indian forces in Kut, surrendered unconditionally to the Turks on 29 April 1916.

Over two years before the war German and Turkish agents started a prolonged anti-British campaign to stir up an Islamic revolt in India. As part of this campaign, they sent agents, led by the legendary German diplomat Wassmuss, to stir up Persian nationalists to rid South Persia of British influence.

In November 1915 Wassmuss persuaded the Persian Gendarmerie to arrest all members of the British colony in Shiraz “Consul, Bank Manager and all”.

The failure of the Gallipoli campaign and consequent evacuation of the Dardanelles in January 1916 and the humiliating surrender at Kut dealt severe blows to British prestige in the Middle East, particularly in Persia and even in India itself. Persia became of critical strategic importance to Britain. Furthermore, valuable British-controlled oil fields in South West Persia came under threat.

In March 1916 Sir Percy Sykes began the task of raising the SPR and stiffened by the 16th Rajputs, they reached Shiraz by November 1916 releasing the British prisoners on the way. This was by no means the end of the affair. Firstly there was the matter of what to do with the 6000-strong Persian Gendamerie; unpaid, ill-disciplined and pro-German. Sykes wisely incorporated them into the SPR on the basis that they would be of less trouble under the supervision of British officers than if left to their own devices. “History can teach lessons but it is doubtful if President Bush or his aides had studied such an obscure campaign when they decided to disband the Iraqi Army”. The German agents, with the exception of Wassmuss who escaped, were rounded up.

Another problem was a nomadic tribe called the Qashqai. They could best be described as wild independent brigands who could muster a well-armed force of 5000 cavalry and who thrived on extortion in an otherwise lawless land. They had no interest in seeing British or Persian authorities imposing the rule of law. Besides their chief was a friend of Wassmuss.

My father, like many of his generation, was singularly reticent about his exploits. Casualties in South Persia were light by Western Front standards but many died and many more were wounded. My father told of a delegation of the Indian officers in his company. “Sahib they said, we are loyal soldiers of the Sirkar (the government) we do not fear death but we are very concerned about the wounding”. And they had a good cause. Medical supplies were rudimentary in the first place and because of the activities of the Qashqai, who most of the time, controlled the road to the coast, they often ran out.

The enemy was sometimes armed with ancient Jezails (muskets firing balls). I now possess a leather-bound pocketbook worn by one of my father’s officers that deflected a musket ball thereby saving his life. Sadly he was killed later on that day. Engagements took the form of small-scale but sometimes bloody skirmishes. In the morning at dawn, he used to ride out to relieve the pickets on the hills surrounding Shiraz and then it was back “licketty split” (my father used this expression in place of “at a gallop”) for a hearty breakfast in the beautiful walled garden of the Bagh-i-Samed- Aga, the house that was their Mess.

The incorporation of the Gendarmerie into the SPR was not entirely successful and there were a number of mutinies. Margaret Ferguson, the writer, gave this contemporary and most politically incorrect eyewitness description of the SPR. “This body of men, never to attain any great standard of valour and dependability in spite of the gallant efforts of the British officers was only in its very raw days then and our armed escorts weren’t very impressive in appearance.

Recruited from the mongrel coastal tribes, they were dark-skinned, sullen-eyed, untidy individuals, who slouched along with their sheepskin hats on the backs of their heads and their rifles slung anyhow over their shoulders”. On one occasion the SPR were tasked to escort a camel train of specie from Bander Abbas on the coast to the bank in Shiraz. On the way, part of the escort, tempted by the species, mutinied. Many however remained loyal and thanks to determined leadership by Capt Wall and a British NCO, “Could it have been Sgt Dickerson?” The mutineers were seen off and the specie saved.

My father with a detachment of reliable 16th Rajputs was then tasked to escort the specie on to Shiraz. This specie was required in Shiraz in order to “Buy Off” the Qashqai. On one occasion my father was out riding alone when he was abducted by a group of Qashqai. My father’s captors were aware of the cash being paid out by the British to restrain their brigandly habits and he was able to persuade them that they would be well rewarded if he was returned to the British lines unharmed.

For all their faults and despite the mutinies, the SPR, stiffened by the 16th Rajputs and a few other supporting Indian troops, secured South Persia for the British and when Russia slid into revolution in 1917, enabled British influence to spread into the north of the country. German influence in the area was overcome, the oil fields secured and the Turks were that much more easily defeated.

Had Sgt Dickerson and the handful of other British officers and NCOs that served in the SPR and the detached Indian Army contingents failed in their duty who is to say that the entire course of the Great War might have been altered?

My father was fond of quoting Marlowe “Is it not passing brave to be a King and ride in triumph through Persepolis” but the reality was that he rode there often on convoy duty and it was just a place where he camped. The magnificent ruins, he later told me, conveyed little then to him and his Rajputs.

The campaign, though taking place at the same time as the industrial destruction of the Western Front, was conducted under conditions that Wellington would have found familiar in India over a hundred years before. Transport was by horse, mule, donkey or camel. Rations were “on the hoof”.

Dispatches were carried on horseback. and when the sun shone the heliographs, flickered between the hills, always provided that the stations could be protected from the Qashqai. Disease, particularly cholera and influenza killed far more men than the enemy. My father survived unscathed and by the end of the war had reached Mesopotamia.

Sgt Dickerson returned to the 7th Hussars in 1919 and stayed with them until 1928 when he was discharged as a SQMS after 21 year’s service with a record of exemplary conduct.