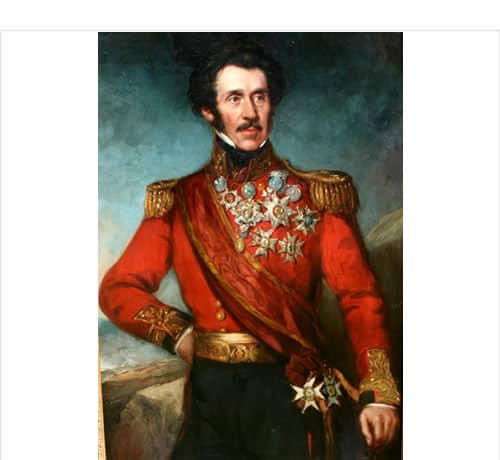

George de Lacy Evans was born in Limerick in 1787, the son of a farmer and modest landowner, and of Elizabeth Lacy of the Anglo-Norman de Lacy family. Staunch Catholics, the de Lacys opposed the Protestant settlement.

RMA Woolwich and India

George De Lacy Evans Evans was educated at RMA Woolwich and joined the Army in India in 1806, as a volunteer, and was commissioned in 1807 into the 22nd (Cheshire) Regiment. He first saw action the same year against the Amir Khan and the Pindaris.

From the outset of his career, in the campaign against Amir Khan, he demonstrated an instinctive boldness and daring and was promoted to Lieutenant for his services. Seeing further active service, which had met the approval of the Duke of York, the Commander-in-Chief, he transferred in 1812 to the 3rd Regiment of Dragoons, then serving in the Iberian Peninsula.

The Peninsular 1812 -14

He took part with the Regiment in a number of Peninsular battles, among them Vittoria and Toulouse, during which he was wounded and had two horses shot from under him.

During the retreat from Burgos (October 1812) he participated in the rearguard actions …. he led his cavalry detachment in several audacious charges which delayed the French.

In the action on the Hermoza river, he was wounded but remained in the saddle as an example to his men. Evans fought in all the principal battles in 1813 and 1814.

At Vittoria he led several charges in the final rout, capturing prisoners, an artillery piece and large sums of money. Praised for his exploits by Lord Charles Manners, his commanding officer, he earned similar plaudits for his daring in the battles of Sorauren.

As the French retreated through the Pyrenees, Evans had a horse shot from under him at Bayonne and distinguished himself in the actions of Nivelle, Orthes and Tarbes. In the final Battle of Toulouse (10 April 1814) he was twice wounded and had another two horses shot from under him.

Though frustrated by the Cavalry’s supporting role in an essential infantry campaign through mountainous country, Evans offered his services as an engineer in the trenches before San Sebastian and to join the assault on the fortress. He was also active in the siege of Pamplona.

Also frustrated at lack of promotion and the purchase system, his courage and abilities were marked by a short attachment to the Quartermaster General’s Department (13 March-25 May 1814), which presumably led to his appointment to the staff of General Ross, the commander of a division sent to join Sir Alexander Cochrane’s fleet off the coast of the United States.

The United States 1814 – 15

Evans sailed for the Chesapeake Bay as Deputy Assistant Quartermaster General with General Ross in the Royal Oak, arriving on 16th August.

Cochrane decided to attack Washington by the Patuxent River, to destroy a flotilla of gunboats and cross the intervening 16 miles to Washington. As Deputy Assistant Quartermaster General, Evans was concerned with logistical problems, and deployment. Ross’s column marched up the West Bank while Cochrane’s Squadron forced the gunboats to scuttle.

Ross then marched on Washington, overcoming strong resistance at Blandenburg, where the British lost 64 killed and 185 wounded.

During the battle, Evans displayed his customary elan. Acting as Quartermaster General, he disposed the troops on the field. The same day he personally reconnoitred Washington, proposed its capture, and volunteered to lead a storming party of one hundred Infantry in a night attack upon the City. Evans led the attack, dislodging a few enemy soldiers, and gaining possession of the Houses of Congress before any other troops arrived.

For his services at Blandenburg and Washington, Evans was mentioned in dispatches and recommended ‘for some distinguished mark of approbation’. In a separate dispatch, Ross wrote that “the success of the expedition must be attributed ‘chiefly’ to the ‘perseverance and indefatigable exertions’ of Evans”.

Evans, who had been mentioned five times in dispatches from America, was promoted to a Captaincy’. Spiers comments that “this was a fairly typical form of promotion.”

Finally, he took part in Naval Operations before New Orleans, where he was the only Army Officer to receive the Naval General Service Medal for his action.

Waterloo

Evans arrived at Spithead and found Wellington organising another Army to meet Napoleon. Evans was awarded a Brevet Majority and joined Wellington’s Army as a Deputy Assistant Quartermaster General. He soon saw action.

At Quatre Bras on 16th June Evans assisted in the deployment. On 17th June, Anglesey ordered “Evans to accompany Sir John Elley, the Adjutant General of the Cavalry, in a reconnoitre of Genappe.

On 18th June, Evans served as A.D.C. to Sir William Ponsonby, Commander of the Union Brigade. Deployed in a long hollow behind a ridge held by Picton’s 5th Division, the Cavalry was concealed from view and screened from cannon fire.

Evans, who had passed the order to form also, at Ponsonby’s request, ordered the charge when the enemy crossed the road. “He took off his hat and waved the Brigade forward.”

“The charge, as recalled by Evans, was a dashing and decisive affair which degenerated into chaos and confusion, and nearly resulted in disaster. Initially the French, on reaching the crest of the position, appeared to be nearly ‘helpless’. The cavalry seized the opportunity; it moved forward and charged down the hill, taking some 2,000 prisoners and two eagles.”

The enemy wrote Evans: “fled as a flock of sheep across the valley quite at the mercy of the Dragoons – in fact, our men were out of hand. The General of the Brigade, his staff and every officer within hearing, exerted themselves to the utmost to reform the men, but the helplessness of the enemy offered too great a temptation to the dragoons and our efforts were abortive”.

“Anticipating that the French cavalry would exploit the ‘disorder’, Evans rode back to the infantry lines and persuaded Sir James Kempt, now commander in place of the mortally wounded Picton, to provide cover for the ‘inevitable’ retreat.”

General Sir A. Clifton, in his account of the cavalry achievement, praised “the gallant and admirable conduct of Major Evans”.

“Even more important, Evans assisted in the reorganisation of the Brigade. During the remainder of the battle the three regiments, reformed on a two squadron basis, guarded the rear of squares formed of raw second-line troops, mainly Brunswickers and Hanoverian militia. Later they joined in the counter-attack on Ney’s cavalry”.

“Major-General Sir Denis Pack, who had commanded one of the Brigades of the 5th Division, recommended Evans for promotion, particularly for his services in the latter part of the battle. The recommendation was acted upon directly and he was made a brevet lieutenant-colonel, bearing the date 18th June 1815.”

He had been promoted to Captain in January 1815 for his Peninsular services, Brevet Major in May 1815 for the American War, and Brevet Lieutenant Colonel for Waterloo in June 1815: three promotions in six months.

Retirement – 1815-1835

After Waterloo, Evans continued on the Staff until he retired on half-pay in 1818, to prepare for a political career so that he could pursue an agenda of radical reform. Concurrently, Evans unsuccessfully sought active service. His radical views on Army reform probably prejudiced his chances and there were to be only two further periods of active service, totalling four years – as Commander of the British Legion in the Spanish Carlist Civil War and of the 2nd Division in the Crimea.

Evans’ Political Career

In the 1820s, Evans became known through his writings, such as his warning of Russian threats to India. The Times took up his 1828 pamphlet On the Designs of Russia, leading to the Government and East India Company initiating studies. Sir John Malcolm, the Company’s adviser, concluded that while there was no immediate threat, Evans’ warning was timely.

In 1830, Evans entered Parliament for Rye. From 1833, he sat for Westminster for most of the years until he retired in 1865. In 1834, Evans married Josett Arbuthnot, a wealthy widow, so becoming financially independent. In 1841 he received £20,000 from the estate of a political admirer.

1835-1837 – A Summary of the Carlist War

In 1834, Britain, France and Portugal backed the Spanish Constitutional or Cristino cause (after Maria Cristina, Queen Regent), against Don Carlos, the absolutist claimant to the throne. In 1835, Palmerston’s Whig Government acceded to a Spanish plea to recruit a Legion of 10,000 auxiliaries. Tory opposition was heightened by the Spanish request for Evans to command (with the local rank of Lt. General).

Commanding the Legion proved a demanding task. It required military expertise, diplomatic dexterity and some understanding of Spanish economic and political problems … Evans neither spoke Spanish nor had any experience of field command. Untested in diplomacy, he had not proved particularly adroit in the handling of sensitive political issues. On the other hand, he was fully committed to the Constitutional or Cristino cause …. He had seen active service in Spain. At the age of forty-seven, he was still physically fit and a capable horseman. He had, too, a presence which would evoke the respect, even the admiration, of the rank and file.

Evans did not share the Government’s extravagant expectations for a force that would be too small to act decisively on its own. He did believe the Legion’s presence was a statement of support for democratic government and that the Legion co-operating with others could cut the Carlists’ supply route. Evans was to show that he had lost none of his instinctive feel for the battlefield and that his offensive spirit and optimism could still lead to rash decisions.

The Spanish quickly recruited Legionaries, the first detachments reaching Spain in July. However, medical vetting was cursory and only a third were from agricultural trades and therefore the best suited to campaigning. These were mainly Irish. The remainder came from the unemployed of the big cities; factors that were to contribute to the winter’s casualties at Vitoria. Evans was responsible for finding officers, but Wellington had forbidden officers on leave from serving. Evans found competent senior officers from among his friends and six on leave from the East India Company. Some one hundred had served as mercenaries or came from the ranks, but most of the four hundred were adventurers, who had seen no service. Though brave, some lacked the rudiments of discipline.

August 1835 – Evans lands in San Sebastian to find the first detachments training. He makes a hurried abortive assault to raise the city’s siege.

November 1835 – After Carlists had lifted their siege of Bilboa, Cordover concentrated his forces around Vitoria to blockade the Carlists to the North. The Legion “arrived on 3rd December, having completed the last march of about twenty-four to twenty-eight miles without a single straggler”. By early November, Evans had become concerned about mounting pay arrears. This problem would bedevil the Legion and contribute to the hardship of the coming winter, to low morale and ill-discipline. Neither Villiers, British Ambassador in Madrid, nor Evans’ emissary, Colonel Wylde, could obtain satisfaction, nor persuade the Spanish to honour their promises of accommodation and supplies at Vitoria.

December 1835 to April 1836 – The Legion was quartered around Vitoria in deplorable conditions. Bereft of adequate accommodation, firewood or bedding, soldiers slept on boards or flagstones, without any covering except their clothes, which were often saturated. The food which stretched to one meal a day was generally disgusting. Thick snow and the deep mud of thaws compounded the misery and there was no money for ameliorating conditions. Fever and dysentery killed some eight hundred of the seven thousand quartered near Vitoria and a further eight hundred sick were left behind when the Legion moved North.

April 1836 – The Legion began returning to San Sebastian

5 May 1836 – Evans made an audacious assault on the Carlist fortifications to the West of the city. The fortunate arrival off the coast of Phoenix and Salamander under Lord John Hay, with a balance of two regiments supported by the ship’s guns, saved the day. Nevertheless, through Hay’s arrival was fortuitous the strategic and diplomatic significance of the victory were manifest. The Legion had proved its mettle, so strengthening the case for reinforcements.

Impressed by the gallantry displayed by the legionaries and the leadership of Evans, Lord John Hay was convinced that if Evans had 10,000 men … he could ‘clear the whole of this part of the country.

May 1836 – Construction of defences to protect the Bay of San Sebastian

28 May 1836 – A mixed force supported by thirty guns and those of Phoenix and Salamander took the port of Pasajes. By a swift offensive, with little loss, Evans had captured a vital port and established a foothold on the coast of about nine miles in extent.

31st May, 6th and 9th June 1836 – Evans defeats counter attacks on his defences protecting the Bay of San Sebastian.

11th July 1836 – Evans attacked Fuenterrabia on the French frontier to close the Carlist supply route. Though Evans was too ill to command, he was responsible for this failure as he had not included any guns in the assault force, relying on false intelligence that the Carlists were evacuating the town and dismantling their guns. Although the attack had not been pressed and the troops had remained steady, this failure further lowered morale, again depressed by pay arrears. Some Scots had been informally recruited and wished to leave after a year instead of the normal two.

Discontent led to mutinies in August when Evans was severely ill and unable to address the mutineers. Morale improved with their departure.

1st October 1836 – Some 10,000 Carlists, supported by heavy artillery, tried to recapture Pasajes. Evans’ defences held firm and he was ordered on to the defensive. Evans was constantly to the fore throughout the action, riding from one part of the line to another, in complete disregard for personal safety. With inactivity, the Legion again became preoccupied with problems of pay and conditions. A further mutiny was quelled.

25th December 1836 – The Carlists besieging Bilboa, having been defeated, withdrew Eastwards through Durango. By mid-February, they had concentrated some 16,000 troops in Evans’ area behind the Hernani position

January 1837 – General Saarsfield proposed that the Legion, the Army from Bilboa and his own from Pamplona, should converge on Oyarzun (near Irun), to clear the N.E. of the Carlists.

18th February 1837 – Evans was ready to begin operations, but Saarsfield found continuing reasons to delay. Evans, appalled, was still determined to move as quickly as possible.

10th March 1837 – Evans began an offensive towards Hernani, the key to the Carlist position West of San Sebastian. He crossed the Urumea and carried the fortified heights beyond. Despite heavy casualties, the day’s results exceeded expectations. The same day the Bilboa army left for Durango, where it halted for resupply, instead of pushing on Eastwards, as planned.

11th March 1837 – That evening, Evans received Saarsfield’s letter of 9th March indicating moving “within forty-eight hours towards ‘the enemy’s centre of operation’. Evans was astounded; he concluded that Saarsfield was no longer marching upon Oyarzum, but through the mountainous pass towards Hernani. He claimed that he now prepared a frontal attack on Hernani to divert Carlist forces from Saarsfield’s column. “Even if true, this hardly warranted attacking, with insufficient forces, against a town so vital to the Carlist cause.” [Saarsfield’s plan could have succeeded but depended upon the coordination of the three armies. Evans’ attack was well planned and executed. But heavily outnumbered, he should not have moved until the other armies began to put pressure on the Carlists.]

12th – 15th March 1837 – Evans sent three battalions in boats across the Urumea to capture the village of Loyola, constructing a pontoon bridge on the 13th. Despite the incessant rain, he continued his advance on the 15th having received Saarsfield’s further letter confirming that he had left Pamplona that same day by the “shortest route to the enemy’s lines.” Evans moved in two columns against the hill fort of Oriamendi and the fortified hills which extended from it and covered Hernani. After a fierce resistance, the Carlists were driven from their positions by the bayonet. On the following morning, he began to bombard Hernani. Not until the afternoon of the 16th did Evans learn that Saarsfield had returned to Pamplona because of bad weather.

The prospect of victory vanished with the arrival of Don Sebastian, the Carlist commander, with some eleven battalions, cavalry and artillery. He counter-attacked on both flanks, passing three battalions around Evans’ Left flank, panicking two of his battalions which fled, spreading disorder through the Left, who fell back in disarray.

The Right flank held firm, but Evans outnumbered two to one and with no prospect of Saarsfield’s support, ordered the destruction of captured guns and the dismantling of defences at Oriamendi, before withdrawing to San Sebastian.

Evans was profoundly depressed. He blamed himself for taking a risk in pressing the offensive and for deploying his force “on a strong but too extended position.” He could not excuse Saarsfield’s incapacity or the panic of some battalions. He accepted that the significance of the defeat was not in the casualty list but in the loss of “prestige and morale of our troops”. Evans spoke of resigning, but was persuaded to stay and was soon convinced that the enemy had lost more than the Legion and that a fresh initiative could soon be mounted with reinforcements. Later, Don Carlos had moved his main army Southwards, leaving some 14,000, including armed peasants, to defend the Northern positions.

3rd May 1837 – After receiving reinforcements, Evans again crossed the Urumea and reoccupied Loyola and Aquirre. On 14th May, Evans seized the heights overlooking Hernani. The enemy yielded after nominal resistance, facilitating an immediate attack on Hernani which fell before nightfall.

16th – 18th May 1837 – Evans cleared the remaining Carlist frontier towns of Oyarzun, Irtun and Fuenterrabia, now defended by only three battalions. On 16th May, Evans scattered the two battalions before Oyarzun, investing Irun by noon. He allowed women and children to leave and ordered that prisoners should be spared. On 17th May, after his guns had breached the defences his troops scaled the parapets and cleared the town. On 18th May the garrison at Fuenterrabia sent two officers to Irun to confirm that the prisoners were alive. On their return, the garrison surrendered and pressed Don Carlos to rescind the ‘Durango Decree’.

Lord Palmerston applauded the victories and “‘the concentration of the forces at San Sebastian in accordance with Evans’ advice’.” Despite pressure to continue in command, the exhausted Evans was determined to return to defend his record in Parliament, where the Legion had endured two years of caustic comment from the Conservatives and sections of the Press.

Retirement – 2 1837 – 1854

Evans was vindicated by retaining his seat in the 1837 election and by the award of the K.C.B., and the Orders of St Ferdinand and Charles III. After a further period of retirement and as a Member of Parliament he returned to active service for the Crimea as a Lieutenant General in 1854. but the bitterness remained until his military qualities were recognised on his return from the Crimea.

The Crimea 1854 – 55

Since the Carlist war, Evans had only been promoted once, to the rank of Major General and had little hope of a field command until Wellington died in 1852. Lord Hardinge succeeded as Commander-in-Chief. A pragmatic reformer and supported by Sidney Herbert, the Secretary of State for War and Prince Albert, Hardinge established a School of Musketry at Hythe and adopted an earlier idea of Albert of testing part of the Army in a military camp. In June 1853, a Division was assembled at Chobham to exercise units of all Arms at brigade and divisional levels.

Evans was offered a brigade and figured prominently and successfully in the first month’s exercises. On 29th August, he was appointed Colonel of the 21st North British Fusiliers. On the outbreak of war with Russia in 1854, Evans, then 67, was given command of the Second Infantry Division. He was the most experienced of the senior Generals as no other had had Evans’ Carlist War practice of handling forces of all arms, or of maintaining a force under difficult conditions.

Evans took command of the assembling forces at the rear base at Scutari until Raglan’s arrival. Evans’ care for the Army’s health and the thoroughness of his own Division’s training, had soon established his reputation and his division was highly regarded. He commanded the Second Division at the Alma, where he and his Division ensured success, and at “Little Inkerman”.

The Alma

The road to Sebastapol crossed the Alma, some two miles from the Black Sea Coast, by a raised causeway and ford before climbing a pass through steep hills, closely overlooking the river. The Russians held these hills in great strength, with their position based on their “Great Redoubt”, on the hill to the East of the pass. Massed guns dominated the Causeway and pass. Heat and smoke from a burning village increased the attackers’ problems.

The Allies advanced with the French on the right between road and sea and the British on the Left. Evans’ Division attacked astride the road to clear the pass, with the Light Division on its Left, attacking the Great Redoubt. He sent General Adams with two battalions (49th and 41st) with artillery to the Ford, which was the boundary with the French.

Evans, with the First Brigade, the 47th and one battery of field artillery, moved along the exposed Causeway under fire from the sixteen guns of the Causeway batteries and eight other guns deployed nearby. They were also enfiladed by the Great Redoubt’s heavy artillery and their advance was met by the fire of Russian infantry screened by the smoke. Evans was supported by 18 guns, including batteries from the First and Light Divisions, volunteered by the battery commanders. The Infantry advanced gradually under a hail of grape, canister and musket balls, finding some shelter in the walls of buildings. Evans observed the advance from a hillock just clear of the smoke and opposite the Russian batteries.

Concerned at the fate of Adams’ brigade, on the right, he dispatched his Deputy Quartermaster General to reassemble its scattered forces. Meanwhile, Pennefather’s brigade and the 47th pressed forward, eventually crossing the river and reforming under the steep bank. Losses had been severe. Evans was wounded in the right shoulder, almost all his staff had been struck and Pennefather’s brigade had lost nearly half its strength in killed and wounded. Moreover, some companies of the 95th (Left Battalion) had merged with the Light Division attacking the Great Redoubt.

Evans ordered his shattered regiments to hold their ground and engage the guns in front with their Minie rifles. Waiting for an opportunity to advance, he heard the sound of a British 9 pounder shelling the enemy position. Captain Turner had reached Lord Raglan’s forward knoll with two guns, from which he had begun to enfilade the artillery astride the main road. As the shelling was soon followed by the limbering up and retreat of the Russian batteries, Evans seized the initiative. He mustered his three Regiments, the 47th, 30th and 55th, for an advance and annexed artillery to provide support.

To his own battery, he added the two batteries apparently neglected by the commanders of the Light and First Divisions and two more batteries proffered by Sir Richard England from the Third Division. With about thirty guns at his disposal (a few were lost in the river crossing), Evans advanced into the pass. While the 55th, under Colonel Warren, moved up the valley to support the Royal Fusiliers [Light Division] by firing on the left flank of the Russian [Great Redoubt] position, Evans established his guns near the site of the batteries that had just been withdrawn by the Russians.”

About halfway up the hill, Evans ‘saw in profile the swift disordered advance of Codrington’s [Light Division] Brigade’, and feared that one of his regiments might be driven back to the Alma.” He saw, too, that the First Division was still stationary on the northern side of the river and sent Colonel Steele, the Military Secretary, to the hesitant Duke, informing him ‘that he was the bearer of orders from the Commander of the Forces’, and that the First Division ‘should forthwith pass the river and proceed as rapidly as possible to support the troops under Sir George Brown’ [Light Division]. Evans assumed full responsibility for this action, which prompted the Duke to resume his advance.

Little Inkerman

When the Army arrived at Sebastopol, Evans was ordered to guard the extreme Right of the British position and so occupy the heights of Mount Inkerman – the Seaward flank. Evans had insufficient troops to defend the whole ridge. His Division was down to about 3,000 and he had to supply working parties for the siege, so had few men to build adequate defences. He, therefore, concentrated his forces and protected the line of communications with the rest of the Army. He, therefore, refrained from guarding the top of the ridge, known as “Shell Hill”, as he could not easily support it. Instead, he posted picquets astride that ridge, and sited his camp some 1,300 yards to the S.E. beyond a small crest, “Home Ridge”, where he could maintain contact with the nearby Guards camp.

Evans was now suffering from a “chronic complaint” and from diabetes, whose effects worsened during the bitterly cold nights. Whenever northerly winds swept through the camp he remained in his tent, sometimes for twenty-four hours, giving and accepting orders through his unopened tent doors and receiving members of Lord Raglan’s staff while lying in bed, or huddled on the ground.

At mid-day on 26th October, Colonel Federoff led six battalions of infantry and four pieces of light artillery (some 5,000 men) in an assault against Inkerman ridge. Despite overwhelming odds, the picquets of the 30th and 49th fought on tenaciously. Evans determined to fight on the ground of his own choosing. He only sent two companies to support the picquets and assembled eighteen guns on ‘’Home Ridge”, his own battery, and another from First Division. He also deployed the Brigade of Guards that had been brought up by the Duke of Cambridge to secure his right flank.

As picquets withdrew, outflanked by the three Russian columns, they positioned themselves behind the walls on the ridge. Evans’ artillery destroyed the guns on “Shell Hill” and broke each of the three Russian columns in turn. Within minutes the whole force was in retreat pursued by the picquets and Evans’ division.

During the half hour’s engagement, the Russians had lost about 600, with another 80 taken prisoner. Evans’ losses were 12 killed and 77 wounded. He never commanded troops again.

After the battle, he was ill in bed for several days. When he returned to duty, he was still so weak he fell from his horse and was seriously injured. Now utterly prostrated, he was evacuated and hospitalised on board a ship in Balaclava.

Inkerman

On 5th November, Evans heard the sound of prolonged gunfire coming from Inkerman Ridge and left his sickbed, with the help of a mercury stimulant, and rode to the battlefield to support his deputy, General Pennefather, and encourage his troops by his presence. It appears that a Captain E.B. Hamleywas speaking to him when a shell, crashing through some obstacle close by, rose from the ground, passed a foot or two above our heads, and dropping amid a group a few yards behind us, exploded there, wounding some of them, but Sir De Lacy did not turn his head.

Retirement – 3 1855 – 1870

After the Crimean War, in February 1855, De Lacy Evans returned to the House of Commons to a hero’s welcome. He entered to a standing ovation and the Speaker announced that the House had agreed nem con a resolution – a very rare honour, as follows.

‘That the thanks of this House be given to Lieutenant General Sir De Lacy Evans, Knight Commander of the Most Honourable Order of the Bath, and to the several other officers, for their zeal, intrepidity and distinguished exertions in the several actions in which her Majesty’s forces have been engaged with the enemy.’

Beginning in the middle 1850s Evans became a strong advocate for reform of the British army. In particular, he was harshly critical of the system by which British army officers purchased their commissions and were expected to pay for each rank of promotion. While he did not live to see the final abolition of the purchase system which occurred in 1871, his persistent call for amelioration was instrumental in its ultimate demise.

For these services he was made a GCB and received the Legion of Honour, the Turkish Order of Medjidie and a presentation sword from Hythe, Folkestone and Sandgate.

De Lacy Evans was a friend of Major General John Gaspard Le Marchant, a 7th Light Dragoon who founded the Royal Military College, later the Royal Military Academy, Sandhurst.

He was promoted to full General in 1861 and died on 9 January 1870, aged 82, and is buried in Kensal Green Cemetery, London.