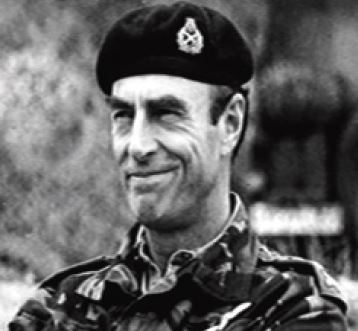

Brian Kenny’s career and achievements as a senior officer have been covered extensively in obituaries published in the leading national newspapers following his death, one day after his eighty-third birthday in June 2017.

They will not be repeated here, but what a career it was:

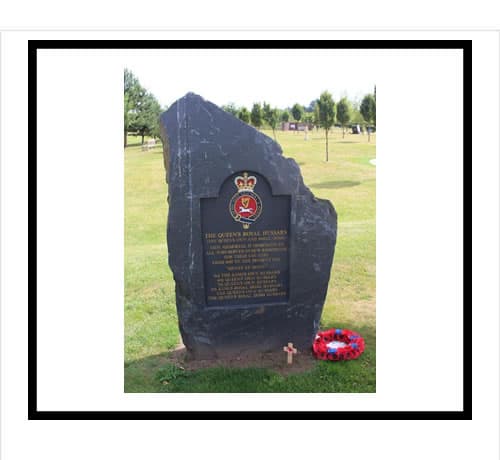

Sword of Honour at Sandhurst, Commanding Officer of the Queen’s Royal Irish Hussars, Brigade Commander, Divisional Commander, Corps Commander, Army Commander, Deputy Supreme Allied Commander Europe; his rise through the ranks of the British Army was unstoppable. Progress was made even more remarkable by the fact that he was a thoroughly nice man.

He was first commissioned into the 4th Queen’s Own Hussars in 1954, four years before that regiment was amalgamated with the 8th King’s Royal Irish Hussars to form the Queen’s Royal Irish Hussars.

At regimental duty he excelled as a games player, representing the 4th at cricket, hockey (he was to play hockey for the army) and skiing. At Kitzbühel where the regimental team was training for the army ski championships, he and Gus Anson, a contemporary, prowled the cafés and tea rooms lining the ancient high street hoping to find attractive, unattached English girls.

Through a misted window they spotted two ladies who appeared to be exactly what they were looking for. They turned out to be sisters and after a hot pursuit in England, he managed to get Diana to marry him. Together, both deeply committed to the Christian faith, they faced the future with confidence.

Moving away from regimental duty, Brian did a tour with the Junior Leaders Regiment at Bovington before applying for a flying course which led to him serving in Aden in 1961 where the regiment enjoyed the services of 16 Reconnaissance Flight of fixed-wing light aircraft which included four Irish Hussar pilots and the whole of the ground crew. With the regiment, the Flight moved to Ipoh in Malaya under Brian’s command and from where his longing for active service was satisfied during the local war with Indonesia – known subsequently as Confrontation.

Flying over the Borneo jungle, sometimes at tree-top height was exhilarating, as well as testing for both the pilots and their frail two-seater Austers. It was also dangerous, presenting an easy, slow-moving target for any Indonesian patrols making incursions into Malaysian territory. Kenny saw to it that his pilots were well prepared, practising night-landings aided only by land-rover headlights and exercising his men by living rough in the jungle for days at a time.

After this came the Army Staff College were, predictably, he passed out with an outstanding report landing him a top appointment as Military Assistant to the Vice-Chief of the General Staff, Sir Desmond Fitzpatrick, who had commanded the 8th Hussars during the last year of the second world war. He then commanded ‘A’ Squadron in the regiment, at a time when it was mostly engaged in looking after the Gunnery School at Lulworth until, after further staff appointments, including teaching at the Staff College, he took command of the Irish Hussars in Paderborn.

Here as a part of the well-oiled BAOR cycle, he concentrated on training his regiment to give a good account of itself in any future conflict in Europe. An important part of such training was a deployment to the British Army Training Unit Suffield (BATUS) in Canada but it was on his way there by air in 1974 that he was ordered to turn round, put his tanks in moth-balls and transform his regiment into an infantry battalion in preparation for a deployment to Cyprus as part of a United Nations force engaged in keeping Greeks and Turks on the island from slaughtering each other.

No sooner had the young officers and soldiers begun to familiarise themselves with the self-loading rifle (SLR) than, in a bout of ‘great-coats-on-greatcoats off’ so beloved of the Ministry of Defence, Kenny was ordered to forget infantry tactics and prepare to assume an armoured reconnaissance role in ancient Ferret Scout Cars, last seen in any numbers in Malaysia.

These quick changes failed to disturb the equilibrium of either the commanding officer who took them all in his stride with an easy competence and great good humour or his soldiers who, for the most part, were pleased to divest themselves of infantry weapons.

The tour of Cyprus – during which Kenny, now wearing a blue beret, not only commanded the regiment but was also Commander Paphos District – was an unqualified success and the Irish Hussars, amid well-deserved plaudits from the multinational force, returned once again to their Chieftains.

This was a time of experimental change in armoured deployments, as brigades were abolished in favour of task forces – a short-lived, little understood, venture during which Brian was completely unfazed by the inevitable confusion that resulted. He just got on with producing a professional and happy regiment well up to whatever task presented itself.

His soldiers recognised in this sometimes old-fashioned commanding officer delivering inspirational leadership, a gentleman to whom, whatever their rank, they could turn for advice and, if necessary help.

Underneath this easy-going facade, he was, however, unrelentingly competitive, both on behalf of his regiment and personally. At tennis he forged a doubles partnership with Mike Perkins, his brigade commander and an international squash player; they rarely lost but if they did his disappointment, always never less than sporting, was clear for all to see.

He was, on occasions, inclined to be strait-laced: at an officers disco he took exception to the – as he saw it – over amorous shenanigans of some of the subalterns on the dance floor and, next morning, summoned his adjutant, instructing him to ‘sort them out’. The adjutant – luckily unnoticed – had been one of the offenders and found it difficult to administer seriously the required reprimand.

From Paderborn, Kenny became chief of staff of the 4th Armoured Division where he organised the Division’s parade and drive-past to celebrate the Queen’s Silver Jubilee in 1977 – an occasion in which the regiment figured prominently and which was written up in the national newspapers as a spectacular success.

Then began his inexorable progress up the chain of command, all of it in BAOR until his final NATO appointment.

The regiment supplied him with a steady stream of ADCs, a number of whom were on duty as ushers at his memorial service at the Royal Hospital in December 2017 – one of them travelling from Hong Kong to do his bit, an illustration of the regard in which he was held by his personal and household staff.

In 1985, the regiment’s tercentenary year, he became Colonel of the Regiment, an appointment he held until the amalgamation with the Queen’s Own Hussars in 1993. With Brigadier James Rucker – his counterpart in the Queen’s Own Hussars – he steered the tricky process of amalgamation smoothly through the many potential minefields of title, dress, traditions and music – to name only four.

Job done he became Governor of the Royal Hospital and remained in this post until his retirement to Dorset in 1999 where, very much in character, he devoted himself to local causes, notably the creation of the Dorset and Somerset air ambulance.

Brian Kenny was a man whose attitude to not only soldiering but to his fellow men, the Queen’s Royal Hussars would do well to note, remember and put into practice. His standards were high – even demanding – but they were achieved and instilled in others with rare humanity, good humour and understanding.

The army was lucky to have him and his regiment prospered through his presence. They were also privileged to have been the recipients of his wife, Diana’s, selfless Christian commitment, and to her and the family go our thanks and deepest sympathy for their loss.