The Regiment has often been likened to a family. For Maj Blackshaw (known throughout the cavalry as Blackie) and his wife. Muriel, without children of their own, really was their only family. They dedicated themselves absolutely to its welfare with all their great energy.

Blackie was born on 25 January 1916 into a strict family in the East End of London. As a boy, to earn some pocket money, he used to clean the milkman’s dray. Conscientious even in those days, he soon graduated to grooming the pony.

It was from this introduction to the equine world that he became determined to join the cavalry. His father, however, had served in the Royal Navy and was so horrified by what he considered was gross disloyalty that Blackie was virtually disowned. As a result, he lost touch with his family.

Blackie enlisted and in January 1934 joined the 7th Hussars at Hounslow at the same time as Paddy Cleere. Within one year he gained his first stripe. He soon proved such a proficient horseman that he was included in the Regimental trickride that had the honour of performing at Olympia that year.

It was, however, a mixed blessing, as, being by far the most junior member of the team, he was the man who had to lie still on the raised stretcher while the rest of the team jumped over him!

The Regiment moved to Egypt the following year and soon after was mechanised. Blackie was obviously sad to lose the horses, but said in the reflection in later years what a hard life it was: unlike with vehicles, you could not put them away, in a garage overnight or at the weekends, and forget them. Nevertheless, this devotion to the horse, he felt, produced a remarkable degree of comradeship within the Regiment.

The Regiment moved up into the desert some months before the Italians declared war. He was promoted lance sergeant at the age of 23, at the time one of the youngest men ever to be so. [as a Sgt tank commander in ‘B’ Sqn in the Mk VI light tank] During the early fighting in 1940 in the June night attack on Fort Capuzzo, the tank he was commanding was hit [by Italian gunners] and he was badly wounded in the chest and lost an eye. He was evacuated to Cairo in the same ambulance as the Commanding Officer, Col Geoffrey Fielden.

While recuperating in hospital, because of the seriousness of his wounds, he was put on a draft to return to the UK in a hospital ship. He was having none of this and he complained to Mrs Fielden who was visiting the Regimental sick and wounded. Strings were pulled and it was fixed that Blackie should return to the Regiment. This he did to become SQMS of ‘B’ Squadron in time for the move to Burma.

Blackie was a man of unswerving loyalty to the Regiment and always showed enterprise and flexibility in interpreting rules for the benefit of it. He insisted on the exact implementation of sensible orders. but was relaxed on irrelevant ones from higher headquarters.

In the 1,000-mile withdrawal through Burma, the last part of which was on foot, one over-zealous and pedantic SQMS filled his pack with his Squadrons paybooks. Not so Blackie, who reasoning sensibly that they would have no future relevance, [with no likelihood of a pay parade before India] ditched his in the River Chindwin and filled up with a bottle of whisky. This proved a considerable solace to him, Paddy Cleere, and their friends on a gloomy evening on the arduous march.

The Regiment reformed and re-equipped in Iraq where Blackie was moved to RQMS. He became RSM in time for the next move, to Italy, and fought with the Regiment until early 1945 when he returned to the UK together with others who had had over 10 year’s continuous service abroad without home leave. He first became RSM of the depot and then of the Lanarkshire Yeomanry.

In 1949 he returned for a second tour as RSM and held this appointment for five years in Barnard Castle, Luneburg, and Fallingbostel. It was during this time that he did so much to instil a standard of excellence in a Regiment still suffering from the loss of so many of its wartime soldiers. His one eye saw far more than most people’s two and those who thought that his bark might be worse than his bite were speedily disillusioned. But even those that he drove the hardest (he drove no one harder than himself) admitted that he was immensely fair.

He felt that the type of discipline developed in war needed, in peace, to be reinforced by drill, smartness, and knowledge of Regimental history and tradition. The sanctity of the barrack square became the touchstone and woe betide anyone unauthorised who dared to cross it.

At Fallingbostel, he had a forest cut down to construct such a square – this essential element of proper soldiering. His almost ferocious application of these principles and the insistence on standards in the Warrant Officers’ and Sergeants’ Mess were not at the time always appreciated by everyone.

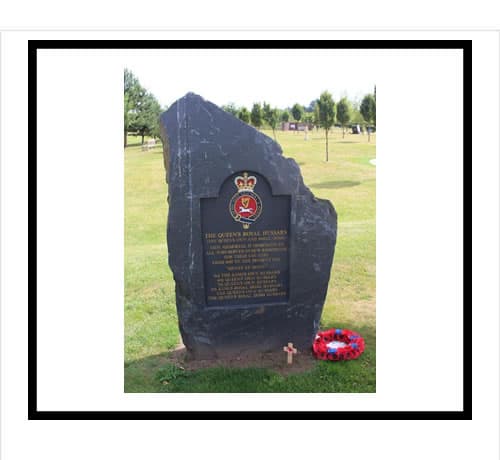

They were, however, necessary and were ameliorated by the long exercises incorporating much of Northern Germany in the face of the Soviet threat. This eventful period included the unveiling of the 7th Hussar War Memorial, the Coronation Parade of Her Majesty The Queen, in London, and the foundation by him of the Regimental Museum, which he built up to over a thousand exhibits. He was awarded a richly deserved MBE in 1953.

Blackie was commissioned in 1955 as a lieutenant (QM) to the Leicestershire Yeomanry, but the following year he rejoined the Regiment in Hong Kong as QM (Tech). Subsequently, he became an outstanding Quartermaster – from keeping immaculate books to materialising apparently impossible requests (even from Sir Michael Parker, then a subaltern, who made such requests for his imaginative, ambitious, and, sometimes explosive, theatrical productions).

He also became something of an elder statesman. Perhaps his proudest moment. however, came when on 20 March 1959 he carried and handed over the new Guidon to Her Majesty, Queen Elizabeth, The Queen Mother. Always proud of being a 7th Hussar, he was no less devoted to the new Regiment after the amalgamation.

Blackie was always resourceful. He had three glass eyes made to replace the one that he had lost when wounded in the desert: a normal one, a lightly jaundiced one for the morning after a particularly heavy Sergeants Mess night. and one backed with the Union standard for the imperial occasion.

In 1960, ‘C’ Squadron arrived in the desert outside Aden to find that progress on the barracks, which was supposed to have been completed, was little more than a line of tents on the sand and stone. Blackie arrived for a visit and it took him only one day to galvanise the Arab labour force (not noted for their enthusiasm for work) into a frenzy of activity.

On the third day he had to go into Aden to organise stores. Not wishing for any slackening of effort, he had the entire labour force assembled and addressed them through an interpreter, interlaced with his own exhortations in a mixture of English, Egyptian slang, and Urdu. To reinforce his point, he took out his imperial eye, which he happened to be wearing at the time, placed it on the table in front of him, and announced that it would be keeping his eye on them while he was away. Although a particularly hot day, there was no slackening.

For the rest of the year that the Squadron was in Aden, the labour force was an example to all of Arabia for diligence. That they lived in terror should the Wahid Shuft return may have had something to do with it. In 1945 Blackie married Muriel. She not only loyally supported him but also became a great Regimental personality in her own right.

She became a wise councillor and helper to generations of young wives of all ranks. At Owermoigne there was always a welcome for Old Comrades. It is only sad that, after they moved to Dorchester, her last years were clouded by such a painful illness. It is perhaps needless to say that Blackie nursed her with exceptional care.

Blackie left Regimental duty for the last time in 1964 on posting to QM at Lulworth. Arriving like a hurricane, he soon sorted out what he considered an inefficient department. He was to stay there in all for 17 years, for, on his retirement from the Regular Army in 1970, he became, as a retired officer, Irnprest Holder and Mess Secretary. During this time, it gave him great pleasure to serve three QOH and one QRIH Gunnery School Commandant. The Mess became a byword for hospitality and Blackie became known to, and admired, by almost every officer in the Royal Armoured Corps.

He retired finally in 1981, but this was not to be the end of his contribution to the Regiment. He always rejoiced in meeting Old Comrades and was a regular attender at Association functions. His great interest in our Regimental history involved him in visits to the museum in Warwick every six weeks, the recording of uniform and regimental insignia, and the Dettingen research project. He was a speaker on one of the battlefield tours. All this work gave him much satisfaction in his declining years.

With the passing of Paddy Cleere and now Blackie, an era of magnificent service to the Regiment, dating back to when the 7th Hussars were horsed, is over. They both joined in 1934 and were close friends, although of almost totally different personalities. They both attained two of the highest ambitions for any soldier, being both RSM and QM of their own regiment. Between them, they held the remarkable record of providing the RSM from 1947 to 1958 – in addition to Blackie’s first tour in Italy. Both of them were devoted to the Regiment and they set examples, which it is hard to follow.

On 2 May 2001, a service of thanksgiving for Blackie’ s life was held in St Mary’s Church, Warwick, only a few hundred yards from his beloved museum. The very large numbers attending were a tribute to the admiration and affection in which Blackie was held. In his Will, Blackie left his entire Estate, which was considerable. to the furtherance of encouraging the study of our Regimental history.

The establishment of The Blackshaw Museum in the Regimental lines will be a permanent memorial to a great Regimental soldier.