George Fielding was three weeks old in 1915 when his father was killed serving with the Sherwood Foresters at Gallipoli. He was raised by his mother in Château d’Oex in the Pays d’Enhaut on the borders of French and German Switzerland and it was here that George spent his school holidays.

After attending Twyford and Shrewsbury Schools and a German course for foreign students at Freiburg University in Baden, George spent a year in Canada on the edge of the Arctic Circle in the company of professional trappers. From there, he sailed for the Argentine where he worked first as assistant to the farm manager on an estancia, then as a cattle buyer in Rosario for Swifts of Chicago. Seeing the clouds of war gathering, he returned to England to enlist.

George joined the Army as an officer cadet at the Royal Military College Sandhurst but his career was short-lived after an altercation with a drill instructor who had ‘booked’ him for ‘soot on hat’ when it was patently obvious that the said soot was coming from a chimney next to the parade ground. He left Sandhurst in disgust and applied instead for a commission on the reserve knowing that this could later be converted into a regular commission.

Originally destined for the Gordon Highlanders, George was befriended by two 3rd Hussar officers at a London nightclub and persuaded that life in a cavalry regiment was preferable to ‘wearing a skirt’. He was duly commissioned into the 3rd The King’s Own Hussars who were then stationed at Tidworth.

After being stationed at Pocklington and Maidwell, the regiment sailed to Alexandria but soon ‘C’ Squadron was dispatched to Crete where its sixteen Vickers light tanks were distributed in penny packets as armoured reserves.

The Germans invaded the island on 20 May 1941 and having survived being dive-bombed by a Stuka, George was shot in the arm by an anti-tank bullet. He was then given the task of marching a group of walking wounded, many of whom were demoralised down to the evacuation point on the beach. An argument broke out when George chivvied a group of Australians who were lagging behind the column to keep up during which one of whom clubbed him from behind with a rifle butt knocking him out.

Coming around in time, George made it to the beach and embarked for Alexandria. He was awarded a Mention in Despatches.

3rd Hussars were awarded a battle honour for ‘C’ Squadron’s contribution to the Battle of Crete.

On return to the 3rd Hussars George served as MTO in the desert and then joined the staff of SIME at HQ MEF in Cairo. Feeling he was doing little there for the war effort, he replied to an advertisement for special duties and in June 1944, was accepted by SOE.

As a fluent German speaker, George was assigned to the Austrian Section charged with raising resistance in the South of the country. Along with two officers and an NCO, he was dropped near Tramonti in Northern Italy, 200 miles behind enemy lines, on the night of 12th August. After a hazardous march north, they established a mission with the Italian partisans at Forni Avoltri, some 15 miles from the Austrian frontier.

It proved impossible to enter Austria in uniform or without documents. George, however, crossed the frontier twice, dressed as a peasant but carrying no papers, to reconnoitre the Upper Gail Valley. He visited a local doctor, known to be anti-Nazi, to assess the prospects of establishing a local resistance movement; but his contact told him to drop the idea. Most of the Austrians were intimidated by the long reach of the Nazi machine, and all the able-bodied men had been conscripted. Instead, he concentrated on establishing safe houses for deserters from the Wehrmacht.

The Germans reacted swiftly to George’s activities, making repeated attacks with regular troops in an attempt to drive him from the area. He relied on the partisans for food, local intelligence and bodyguards; but when air drops of arms and ammunition promised by the Bari-based Balkan Air Force did not arrive, morale suffered and his position became increasingly dangerous.

George blamed these supply failures on the pilots’ unwillingness to fly over the mountains at night, and he was moved to send them a message asking that they display “more of the spirit of the Battle of Britain and less of the bottle of Bari”. This was on his return to spark a furious row with an RAF commander.

The Germans placed a reward of 800,000 lire on George’s head. This should have been an almost irresistible temptation in a poverty-stricken area.

However, George maintained that it was fear of German reprisals rather than the reward that led to the betrayal of his hiding places in barns on two consecutive nights. Fortunately, he was warned on both occasions and moved in time. Two of his group, however, were captured, and in October his group was betrayed and surrounded by Cossacks. Although wounded, he escaped the ambush.

A thousand Alpine troops, a Cossack brigade and two of the best Italian Republican units – a total of 6,000 men – were diverted from the front in a determined effort to eliminate George’s group of 30 partisans and to crush the other resistance groups in the region. Local intelligence became scarce and unreliable, and by mid-November early snow had closed the passes for the winter.

After the Lysander sent to exfiltrate him was shot down by an American P40 Lightning, George was ordered to withdraw what remained of his mission to Slovenia on foot. Having managed to evade the cordon, his group embarked on a gruelling march of 300 miles across the mountains, during which they were short of food and had to ford rivers by night. Finally, they reached Crnomelj and on 27th December they were evacuated to southern Italy.

George was awarded an immediate DSO.

After the war, George bought a mixed farm in the west of Ireland and ran it successfully for nine years before returning with his family to the Pays d’Enhaut.

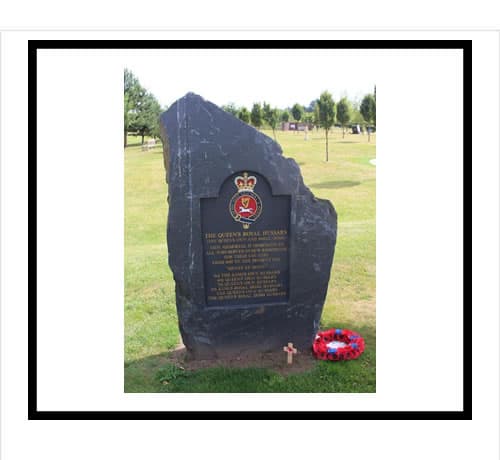

George’s son, Martin served in The Queen’s Own Hussars from 1966 to 1974 and his daughter, Sarah married The Hon. Guy Norrie who served in the 10th Hussars and then The Royal Hussars.

George died in 2005.