By Eric Niderost

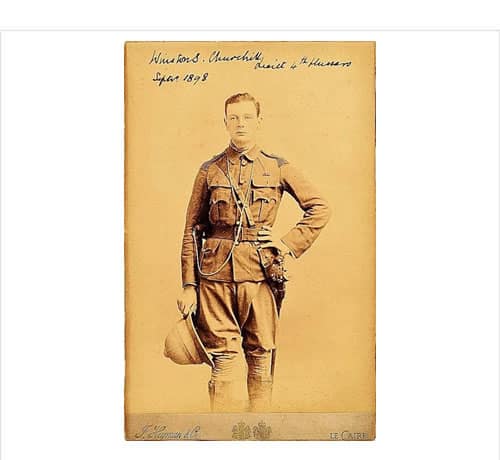

It was the morning of September 1, 1898, the day before the Battle of Omdurman. Lieutenant Winston Churchill of the 4th Queen’s Own Hussars rode out with four squadrons of the 21st Lancers to scout the approaches to Omdurman, a Sudanese village on the west bank of the Nile opposite Khartoum, the epicentre of a revolt that had rocked the very foundations of the British Empire.

An Anglo-Egyptian army under Maj. Gen. Sir Herbert Kitchener was a few miles behind the cavalry screen. Kitchener’s object was to reconquer the Sudan, restore order, and forestall any encroachments from opportunistic European rivals.

The British horsemen cautiously advanced over the sun-baked plain, the eye-numbing sandy desolation relieved by a few thorn bushes, scrub, and patches of grass. Churchill and the lancers ascended a low ridge to scan the horizon. Officers raised their field glasses and were rewarded with a sweeping panorama.

Omdurman itself was in sight, and Churchill recalled later that “to the left the river, steel gray in the morning light, forked into two channels, and on a tongue of land between them the gleam of a white building showed among the trees.”

The white building was part of Khartoum, capital of the Sudan, where the Blue Nile and White Nile converge to form Africa’s greatest river. Nearby, there seemed to be a long, dark smear that the British assumed was a zareba, a thorn bush barrier that commonly served as a prickly fortification in the treeless land.

Some of the enemy, whom the British called Dervishes, could be seen lurking behind the barrier, confirming the officers’ first assumption.

The lancers advanced, supported by Egyptian cavalry, the Camel Corps, and some horse artillery. Dervish horsemen came forward to meet them but were sent packing by dismounted troopers firing Lee-Medford carbines at 800 yards. The lancers halted and waited for the enemy to make the next move.

About 11 am, the distant zareba suddenly sprang into malevolent life. It was made of men, not thorns – thousands of them, so thick that they made an undulating black wave. Churchill was awed by the sight.

The roiling mass, he said, was “four miles from end to end and, as it seemed, in five great divisions, this mighty army advanced swiftly. Above them waved hundreds of banners, and the sun, glinting on many thousands of hostile spear points, spread a sparkling cloud.”

The young lieutenant rushed back to alert Kitchener to the enemy’s latest moves. Filled with a growing sense of urgency, Churchill galloped up the hillside to get his bearings.

Once on the crest he could plainly see the Dervish army’s dark masses in stark relief against the brown, sandy plain. Turning around, he could also view the Anglo-Egyptian army, some 24,000 men, drawn up with their backs to the Nile.

The two armies, separated by the hill’s looming slopes, could not yet see each other, but an enormous clash seemed inevitable. Churchill drank in the mesmerizing spectacle – an irresistible wall of Dervishes about to collide with an immovable force of British and Egyptian soldiers.

His sense of duty breaking the spell, Churchill pulled the reins of his horse and galloped down the hill in search of Kitchener. He briefly dismounted, in part to collect his thoughts and calm his rising excitement.

The lieutenant had seen action before, in India, but this was going to be a major battle, and his pulse quickened at the idea.

The action shaping up at Omdurman might well decide the fate of a continent and the destiny of a people.