Churchill’s first month as prime minister was marked by military setbacks. The Netherlands was overrun, Belgium surrendered: France was falling, and the army sent to support them was cut off and trapped in Dunkirk.

If Britain was to withstand a German invasion on its own soil, it needed to bring that force home.

“I have, myself, full confidence that if all do their duty, if nothing is neglected, and if the best arrangements are made, as they are being made, we shall prove ourselves once again able to defend our Island home, to ride out the storm of war. and to outlive the menace of tyranny, if necessary for years, if necessary alone. At any rate, that is what we are going to try to do. That is the resolve of His Majesty’s Government -every man of them. That is the will of Parliament and the nation.

Winston Churchill, 4th June 1940

The British Empire and the French Republic, linked together in their cause and in their need, will defend to the death their native soil, aiding each other like good comrades to the utmost of their strength.

Even though large tracts of Europe and many old and famous States have fallen or may fall into the grip of the Gestapo and all the odious apparatus of Nazi rule, we shall not flag or fail.

We shall go on to the end. We shall fight in France, we shall fight on the seas and oceans, we shall fight with growing confidence and growing strength in the air, we shall defend our Island, whatever the cost may be. We shall fight on the beaches, we shall fight on the landing grounds, we shall fight in the fields and in the streets, we shall fight in the hills; we shall never surrender.

And even if, which I do not for a moment believe, this Island or a large part of it were subjugated and starving. then our Empire beyond the seas, armed and guarded by the British Fleet, would carry on the struggle, until, in God’s good time, the New World, with all its power and might, steps forth to the rescue and the liberation of the old.”

The remarkable rescue of 335,000 British and French troops from the beaches of Dunkirk by a flotilla of boats of every shape and size was portrayed as a defiant act of essentially British pluck.

But the ongoing evacuation of the British expeditionary force marked a military setback and a significant loss of useful equipment abandoned in flight. British public morale was badly dented by the defeat, however; many lives had been saved in the course of it. With all of Britain’s neighbours across the sea now falling into German hands, the likelihood of Britain being invaded was very real.

When Churchill stood up in the House of Commons to report on the military situation, he could not ignore it. He admitted the very high possibility of fighting on the British mainland, painting a deliberately shocking picture of the forms it might take. Churchill sought to rouse die lighting spirit of depressed people by showing them what they faced. “When we see the originality of malice, the ingenuity of aggression that our enemy displays, we may certainly prepare course for every kind of novel stratagem and every kind of brutal and treacherous manoeuvre.”

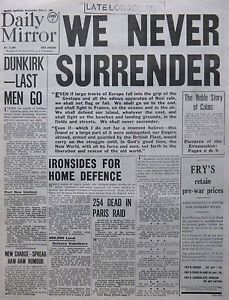

Churchill then expressed confidence in Britain’s ability “to outlive the menace of tyranny” before summing up, in one of the greatest closing passages ever spoken: “We shall go on to the end. We shall fight in France, we shall fight on the seas and oceans, we shall fight with growing confidence and growing strength the air, we shall defend our Island, whatever the cost may be. We shall fight on the beaches, we shall fight on the landing grounds, we shall fight in the fields and in the streets, we shall fight in the hills; we shall never surrender.”

In his speech less than three weeks, earlier Churchill had listed the “blood, toil, tears and sweat” that every man and woman could bring to the fight. Now he listed the places, familiar to all where that fight might happen.

In all the speech drove home the message “we shall fight” seven times; and in that verbal sea of determination, two other phrases leapt out.

“We shall defend our Island”; “we shall never surrender.”

The speech was immediately recognized as a masterpiece of art.

Some MPs cried, and once wrote to Churchill afterwards that “that was worth a thousand guns and the speeches of a thousand years.”