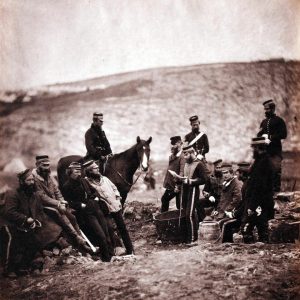

On March 21st 1854, Britain declared war on Russia. Excitement within the 8th Hussars was high at the prospects of going to fight the enemy in the Crimea, and soon the Regiment found themselves under orders to move.

They embarked at Devonport during March on several troop transports and with them went their horses, equipment, the paraphernalia of war. The women who tumbled aboard with them were the soldier’s wives. These the army tolerated, for their usefulness as washerwomen and general camp helpers. Among them, on the S.S. Shooting Star, however, was Fanny Duberly, the wife of Captain Henry Duberley, Paymaster to the Regiment, whose avowed intention it was to accompany her husband throughout the campaign. Three Officers wives had obtained permission to go to the Crimea but Fanny alone was destined to remain the whole Campaign through.

Fanny had been brought up in early Victorian England, an age when feminine robustness and emancipation were not encouraged. But she was a high spirited young woman with a strong character, determined not to be relegated to the parlour, and already by her early teens had become an accomplished horsewoman and proved her courage and daring in the hunting field. It was, therefore, a foregone conclusion that when the opportunity arose to accompany her husband abroad to a life that promised both excitement and adventure, she did not hesitate to say yes.

In spite of last-minute apprehension and fears, a storm-wracked voyage and the loss of her grey horse which she dearly loved, Fanny’s youthful high spirits could not long be repressed and by the time the ship sailed into the tranquil waters of the Dardanelles, once again she was eager for whatever lay ahead. She had not long to wait for her first taste of campaigning, hardly had her excitement lapsed at landing amid the strange and exotic atmosphere of Eastern Bulgaria, then the Regiment was ordered to march.

It was a harsh introduction to a soldiers life and Fanny wrote in her diary: – “Was awoke at half-past two; rose, packed our bedding and tent, got a stale egg and a mouthful of brandy and was in my saddle by half-past five”. Scorched by the sun and choked by thick dust Fanny soon discovered that there lay a vast difference between the almost unendurable agony of jogging along for eight or nine hours in a side saddle and the exhilarating pleasures of the hunting field in England. Completely exhausted she arrived at the new camp. “Captain Tomkinson made me a bed of his cloak and sheepskin and, drawing my hat over my eyes, I lay down under a bush close to my horse Bob. and slept.”

The next three months brought a wearisome succession of moves, and rumour of battle succeeded rumour without the enemy being seen. The intolerable living conditions in the camps were made even more difficult to bear due to the enforced inactivity and the demoralising atmosphere of the phoney war. Food was scarce and that which was available was barely edible. Officer and soldier alike lived in conditions of abject squalor and dirt, filth and vermin became an integral part of everyday life. Poor Fanny did not escape and her fastidious nature suffered miserably. However, an entry in her diary at this lime shows anew her indomitable spirits and sense of fun. “The bugs took lease of me, and the fleas in innumerable hosts disputed possession. A bright-eyed little mouse sat demurely in the corner watching me and twinkling his little black eyes as I stormed at my foes.”

Disease was inevitable under such conditions and soon cholera was raging. Medical stores were few and ineffective and the army was ill-trained to combat sickness. The epidemic quickly spread throughout the army, the Heavy Brigade was soon afflicted and it was not long before it reached the 8th Hussars. Those who were sick stood little chance of recovery and suffered terribly as they lay under the harsh unrelenting rays of the summer sun before they died without hope.

The orders to move to the Crimea came too late to cheer Fanny for by now she herself was unwell. The poor food. hardships of living and anxiety over disease had at last begun to tell on her and the march back to Varna was one of unrelieved misery when each day she doubted her ability to go on. Fanny records how, even when the Regiment bivouacked on the cholera-stricken ground, she was thankful for rest among the victims. “We had appalling evidence of their deaths! Here and there a heap of loose earth with a protruding hand or foot showed where the inhabitants had desecrated the dead … “

The Regiment at last embarked for the Crimea on September 1st, but a dismayed Fanny was banned by the Cavalry Division Commander from going further with them. However, ever resourceful. she outwitted him. Disguised as a camp follower and hardly able to repress her laughter, she hurried past Lord Lucan who was there, scanning every woman who boarded the transports to find traces of a lady. Once onboard Fanny began to relax but her diary records that once again Cholera struck and claimed as its victim an officer of the Regiment. “During his death struggle, the party dined in the saloon, separated from him only by a screen. With few exceptions, the dinner was a silent one, but presently the champagne corks flew-but I grow sick. I cannot draw so vivid a picture of life and death …,”

“Monday, 18th September, at last, today I set foot in the Crimea …,”. Henry had gone before landing with the cavalry on the beaches but Fanny soon set out to find him and with the help of the Horse Artillery astonished him in his bivouac in the outpost lines. It was only the presence of five other officers sharing his tent which deterred her from staying and reluctantly she returned to her more comfortable quarters aboard ship. Thereafter. her daily routine was to go ashore as early as possible and, if she could not see Henry, ride off through the Allied lines, returning only when dusk fell.

The Battle of Alma was fought and the Port of Balaclava captured. Henry was busy and seldom did she see him. It was during this time that Fanny began to write in her diaries of her fears and apprehension for his safety and her grief at the suffering and death of so many men whom she knew, culminating in the entry dated 25th October. “Now came the disaster of the day, our glorious and fatal charge. But, so sick at heart am I that I can barely write of it even now.”

There were few spectators watching the Light Brigade that day and only by the most slender chance did Fanny not miss the Charge. She had been warned by Henry that a great battle was about to commence and, although unwell, had ridden out in all haste not to miss it. On the way, she and Henry narrowly escaped capture or death when they found themselves directly in the path of the Russian Cossacks. thundering in pursuit of the fleeing Turks. Only quick action by her husband saved them and breathless but safe she was able to watch the epic battle. “I only know that I saw Captain Nolan galloping; that presently the Light Brigade, leaving their position, advanced by themselves, although in the face of the whole Russian Force, and under fire that seemed to pour from all sides, as though every bush was a musket and every stone in the hillside a gun. Faster and faster they rode. How we watched them! They are out of sight; but presently come a few horsemen, straggling. galloping back, What can those skirmishers be doing? See they form up together again. Good God! it is the Light Brigade”.

Fanny’s experiences of “Inkerman” were only second hand, but she describes the horror and slaughter that took place. She tells also of the callous and indifferent treatment of the sick and wounded. The field hospitals were farcical and neither good doctors nor trained nurses existed. If a man survived his treatment he was lucky ever again to win back health. The more cynical declared that the luck lay with those who died quickly, with the minimum of pain.

By now Fanny’s fame had spread and the name “Mrs Jubilee” became a byword in the Crimea and she would have been less than human had she not enjoyed the flattery and praise she received. Womanlike, she scorned any rival, and when Florence Nightingale appeared on the scene she did not escape Fanny’s contempt. In England, her exploits were received with very mixed feelings and the reactions of society, including the Queen. were openly critical. They were shocked by her journals and considered her hard. bold and self-seeking. The Queen herself took great pains to refuse a gift sent by Fanny and later when inspecting the 8th Hussars when they disembarked in England, cut her dead. This verdict was unfair for Fanny’s only wishes were to care for her husband and spread a little cheer whenever she was able.

There is much more to tell of Fanny’s adventures but, unfortunately, neither the time nor the space for the telling. Of how, though unwell and without proper winter clothing, for her own had gone back to England by mistake, and existing on little food she made a home for her husband in a small roughly built wooden hut. A home which eventually became the social centre for so many of Henry Duberley’s friends and contemporaries, or how she went on to India with the Regiment and in eleven gruelling months, rode with them for more than two thousand miles in pursuit of the Mutineers. It was there that she became more than the kind “Mrs Jubilee” and emerged an acknowledged leader to whom many a weary soldier gave heartfelt thanks for the inspiration and example she set by her courage and strength.

And so Fanny’s story must end. Not for her were the campaign medals of the Crimea and Mutiny, only the disapproval of a Victorian England which was unable to appreciate her full worth. However, her true reward lay in the wholehearted admiration of the officers and men who knew her on the battlefields of the Crimea and during the long pursuit of the rebels during the Indian Mutiny. To them, she was a truly “Gallant Lady”.

(extract from The Crossbelts 1963)