© Imperial War Museum

On the evening of the fifth day we moved according to plan into the front line.

As each platoon leader and each Hotchkiss section leader had reconnoitred his prospective position therein during the days that we were in support, our relief passed off like clockwork.

The trench was too narrow, as indeed most trenches are, to allow of men in full equipment passing each other without the greatest difficulty, so we relieved on the plan that as soon as our men entered by one communicating trench our predecessors filed out by the other.

Just as the last platoon began to take over, the Hun, having no doubt suspected what was going on, started a brisk little bombardment with trench mortars; but, happily, the deafening, devastating “rum jars” were badly aimed, and, passing high over our heads, fell for the most part harmlessly on to waste space behind us.

The Skipper [Major H.K. Evans, MC] and Purple [Capt. F. A. Sykes], accompanied by myself, had gone up some hours before our soldiery in order to see again the positions by daylight, to take over stores, to discuss the situation generally with the outgoing commander and to go through with him the defence schemes of that area.

We had plodded down our old habitation, Cote Trench, as far as Hargicourt; thence we turned right-handed and walked in the open up the valley of Villeret, which, although under cover from the enemy’s view, was pitted so closely with shell-holes innumerable that they touched one another, till the whole of the ground resembled the surface of a golf ball. In spite of the heavy burden of our kits, we lost no time loitering in that sinister valley of death.

Very fortunately for us, because of the depth and gluelike nature of the mud in them, we were able to get almost the whole way up to our company headquarters under cover without having to use the communicating trenches; and finally, after walking about fifty yards down Railway Support Trench, we came to the little square hole of an entrance in the side of the trench which led steeply down by a staircase of slimy, narrow steps to “Liberty Hall,” our underground dwelling-place, forty feet below.

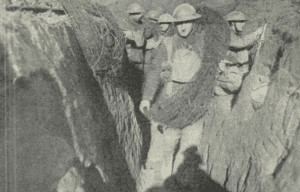

After weeks of snow and frost a thaw came on the Western Front early in February 1917, and the discomforts of bitter cold were succeeded by a sea of mud, some of the discomforts of which Lt Col Beaman describes in this article. What the conditions were is seen in this photograph in which officers of the 12th Royal Irish Rifles are wading through a fallen-in communication trench at Essigny. The Irish Rifles were among the troops that had recently taken over this sector from the French 6th Division To get stuck in such mud might mean an hour’s work of extrication.

© Imperial War Museum

Near the entrance were the wind indicator, the gas gong, and the gas sentry. A gasproof blanket was rolled up, like the blinds of a window, over the entrance itself. Down below were several compartments which suggested, more than anything else, cabins in a ship.

Оnе compartment, fitted with an upper and lower sleep bunk a table, two forms, some bookshelves and a stove, was used as our headquarter messroom. Another was occupied by the telephone and signallers. Another by the HQ staff and mess servants; and the last and largest by as many as it would hold of the two platoons in local support.

The whole excavation was supported by numerous stout pillars of timber, and, to prevent a gradual falling in of earth, the walls and roofs of each compartment were lined with a thick boarding of a finished workmanship.

Nevertheless, well fitted though they were, moisture and earthy slime continually oozed and dripped through the chinks between the boards…

Our front line, Railway Trench, was separated from the German front line by about sixty yards of No Man’s Land; our H.Q., Liberty Hall, situated in the centre of Railway Support Trench, was separated from our own front line by a space of about a hundred and fifty yards of wired waste, which, in merry jest, we called Hyde Park;

Railway Support Trench was connected with the front line by two communicating trenches, called unimaginatively “Spade Trench” and “Club Trench”; and Seylla and Charybdis, twin trench mortars, of which more anon, lurked respectively at the Marble Arch and Hyde Park Corner.

Now, at this time Spade Trench and Club Trench were so deep in mud as to be quite impassable. Indeed, in our local defence scheme we had taken the somewhat unorthodox line of leaving them open to the enemy on the principle of fly-paper. When Purple had been going around the positions previous to our taking over, the officer who guided him had protested that it was impossible to walk down Spade Trench.

This officer of the 12th East Yorkshire Regiment is, with gas-mask and a walking stick, making his last round at Roclincourt on January 9, 1918. He has drawn aside the gas curtain of a dug-out in a snow-covered support trench. From it a pleasant glow from stove and lamps streams out on to the snow. Some of the dug-outs were by this time fairly comfortable dwellings, and in this article Lt Col Beaman describes the accommodation in one of them named “Liberty Hall.”

© Imperial War Museum

Purple, however, feeling that he ought to see for himself, had insisted on trying. After a few steps his guide had sunk up to the waist in clinging mud from which the united efforts of Purple and himself had been powerless to extricate him.

Fortunately, the unhappy officer was wearing thigh gum boots, and, having undone the attachment to his braces buttons, he was eventually, after nearly an hour’s strenuous labour, pulled out of them by five stalwart men, leaving the boots behind him still completely embedded in the mud-from which we were never able to recover them.

Purple was then convinced, and we tried to use those two trenches no more, but followed instead, when it was dark, the tracks that ran alongside each of them.

Through the wire and under cover of some slopes and a slight embankment in Hyde Park we made another track, called Rotten Row, running from our H.Q. through Hyde Park Corner to the extreme right of our front line, along which, with some low stooping here and there, we could get up to Railway Trench totally unobserved, even in broad daylight.

It was, of course, soon marked down by the enemy’s aircraft, and frequently, at irregular intervals, it received attention from many sorts of guns, from rifle grenades, minenwerfer and low-flying aeroplanes, so that its passage was always fraught with excitement and anxiety. As, however, there were so many craters all along and around it in which we could take instant cover, our casualties on it, considering the persistence with which it was bombarded, were extraordinarily light.

Now a cavalry company consists of six platoons. Our turn in the front line was to be for nearly six days it was therefore ordained that four platoons should occupy Railway Trench, two platoons Railway Support Trench, for two days at a time, so that in this way each platoon would have, during the six, two days of comparative repose in local support. The officers of the two platoons in local support lived with H.Q. in Liberty Hall.

The officers of the platoons in the front line each took turn and turn about with their platoon sergeants of four hours on duty and four hours off during the twenty-four; and came back to Liberty Hall for their meals when off duty. Theoretically, then, they had twelve out of the twenty-four hours to eat and sleep. Actually, they got no sleep at all, and often had to go without their meals, for in the front line a thousand and one unexpected things can happen every hour.

On his night round with the Skipper, Lt Col Beaman saw men at work with wire, and shovels and pickaxes. The men of the York and Lancaster Regiment, 62nd Division, are taking up coils of barbed wire through the trenches between Oppy and Gavrelle for a night working party.

© Imperial War Museum

Sudden orders to stand to, gas alarms, raids, spells of hate, distinguished visitors, the noise of gunfire and of bursting shells, making arrangements to get away the wounded, the coldness of those winter nights, the continual passing of persons along the narrow trench and the never-ceasing work of keeping the trench from falling in, made sleep on a narrow firing step a thing of great difficulty, a thing possible only to the utterly exhausted.

The Skipper was on duty from evening stand-to till morning stand-down, that is to say, from an hour before sunset till full dawn; and Purple was on duty from dawn till sunset. Each during his tour of duty twice visited the line and every sentry-a lengthy proceeding; made up and dispatched the reports that fell due during his vigil, answered innumerable questions in code over the telephone, and entertained and supplied with all available information an endless succession of visitors.

These visitors and visits were of all kinds, from the stupendously official to the purely social. The Divisional General himself sometimes dropped in, with a cheery word and a keen eye for any neglect of standing orders. Gunners dropped in to discuss the barrage lines and our latest bottle of port. Sappers dropped in to tell us that our trench was in a disgraceful condition and that wiring parties must proceed to function forthwith in No Man’s Land. The Doctor dropped in to argue Sinn Fein and to express his disgust at our sanitary arrangements.

Every day our own Brigade-battalion Colonel dropped in to see how we were getting on, and to tell us the news. Templeton [Major Tempest-Hicks] also dropped in every day like a fairy godmother to find out our wants in matters of food and drink. Intelligence officers galore dropped in, seeking to suck our brains. Tiny, full of pride and importance in his capacity of Brigade-battalion gas officer, dropped in to prosecute us over our lack of anti-gas arrangements.

Officers of the Regiment which in due course would relieve us dropped in for lunch and dinner and personally conducted tours around our area. Friends, relations, those that were an-hungered, people who had lost their way, refugees when a hate was going on up above, once Hector’s father-who was doing a political tour of the war zone, and who, incidentally, complained indignantly of the way we wasted bread-once, too, a Staff Officer, and others, too varied and numerous to mention, all dropped into Liberty Hall.

Above is the village of Hargicourt through which Lt Col Beaman and his companions trudged on their far from enjoyable evening walk. In the foreground are units of the three classes of wheeled traffic that formed the bulk of that passing along the roads of France and Flanders in war time-a transport lorry and a motor ambulance. Though inevitably badly damaged, Hargicourt was not so completely smashed as front line villages farther north.

© Imperial War Museum

All through the day there was a continual coming and going up and down steep narrow stairs, and a continual crowd and chatter in our subterranean cabin; so it can well be imagined that, during the hours of daylight, there was little peace or repose for our headquarter staff.

But at night it was different. Then there were no visitors. Purple, wearied by the labours of the day, slept soundly on the upper bunk. One of the two subalterns in local support slept soundly on the lower bunk, and the other slept equally soundly on the floor.

The Skipper sat at the table poring over photos and trench maps or wrestling with correspondence by the light of a candle, and I sat by the stove reading the latest war novel, fearfully thrilled by its descriptions of front-line fighting written by a woman who had never left England.

Hector, the Master Bomber [Lt Victor Trew, MC, Squadron bombing officer – ], was also OC Storm Troops. Before coming up to the line he had selected twenty stout men and true, and had carefully trained them in all those arts and wiles of night patrolling by which the unwary Boche might be made a prisoner; and most of the night they lay out in No Man’s Land, stalking their human prey.

At about 11 o’clock on our second night, the Skipper looked up from his maps.

“I’m going around the line now, care to come with me, Padre? It’ll save dragging one of the runners around.”

There was a standing order that no officer should leave the trench without an armed escort.

“Right-ho!” I replied.

We slipped on our leather jerkins, our revolvers, respirators and tin hats, then, grasping our stout trench sticks, we bent double and climbed the forty feet of those shaft-like stairs, tightly holding on with one hand to the rope which, doing duty for banisters, kept us from slipping down off the steep and slimy steps. Outside, the night was inky black. A gas sentry stood at the entrance, close to where three steps led up out of the trench on to Rotten Row.

“Be careful, sir!” he warned us, “There’s a lot of bullets keeps whipping across.”

Rotten Row was not more than a foot wide. On both sides and all around was a maze of thorny wire. Screw pickets and odd strands of wire, which tangled our feet and tore our hands, often crossed the track itself. And the darkness was so dense that we could not see a foot in front of us.

So, feeling our way yard by yard, we progressed exceedingly slowly. I confess that this black and lonely wilderness filled me with many tremors. Every now and then an automatic gun from the enemy’s trench fired a quick burst, and we bent low as the vicious bullets hissed over.

The work of a wiring party and the spinning of their unpleasant webs required no little skill. Above is an unusual example of this work. It is a barbed wire gate which could be let down against approaching raiders, and in the narrow trench they would have very little chance of cutting through it. The scene is in the front line, so the sentry has his bayonet fixed and his gas mask at the ready.

© Imperial War Museum

The double report of a rifle aimed towards you is particularly brutal; it cracks hard and sharp like a smack in the face.

I could not help thinking how little this path was used at nights, and that, if we were wounded, we might lie there writhing in agony and mud for hours and hours.

It was not impossible, too, that Boche patrols, having detected Rotten Row from air photos, could have slipped between the rifle posts in our front line, could have cut and crawled a way through the wire and could be laying up in wait for passers-by.

The thought sent shivers down my already chilled spine. But we reached Hyde Park Corner without mishap. Our eyes having now become more accustomed to the gloom, made out there the Trench Mortar Officer on a visit to Charybdis.

We had early gained the ascendency over this dispenser of unpopular thunders by a judicious mixture of hospitality and firmness. The Skipper shook a playful fist at him. “Don’t you dare shoot off those damn little popguns in my area without orders from me!” he said.

Our system, by agreement with our gunners, was that if the Boche tried to strafe us we let him have it back with every possible means at our disposal, bombs, grenades, crumps, whizz-bangs, and these trench mortars, for about twice as long as he had strafed us. But we sternly discouraged individual and promiscuous efforts on the part of Seylla and Charybdis, as the Boche then replied with trench mortars more than twice as heavy, which played great havoc with our trench and inflicted many casualties.

The Trench Mortar Officer laughingly assured us he would not think of doing such a thing. But occasionally the sergeants in charge of the mortars, from devilment or ennui, fired a round or two on their own, with the result that in a few minutes a vehement and bloody hate of all weapons would be raging. Some yards farther down from Hyde Park Corner we entered the extreme right of our sector of Railway Trench. “Halt! Who goes there?” came a low-voiced challenge through the gloom.

We gave the counter-sign and were permitted to pass. By dint of unceasing labour this trench had been kept in passing good condition. In places the duck-boards floated on water that welled up faster than it could be pumped out; in places there had been recent slips of earth and sandbags, but on the whole the bottom was sound and narrow, the firing step firm and the side adequately rivetted.

Now trenches in France are not straight, but, following the contours of the ground or the fluctuation of a battle, zigzag about in the most irregular manner, and they are manned, not along the whole length, for that would require innumerable hosts, but at intervals only, by numbers of rifle and automatic-gun posts, so placed that the cross-fire from two or more posts covers all ground over which the enemy could possibly advance.

At every post a sentry stood on guard, peering out over the parapet into the shadows of No Man’s Land, while the remainder, who were not employed on fatigue, patrol, wiring or listening post, tried to sleep on the firing step. After giving the counter-sign at each post the Skipper stepped up alongside its sentry and chatted with him in low tones for a few moments.

I noticed particularly how few lights were being fired up from the trench, which is generally a sign of steady nerves, as is, conversely a multitude of lights the sign of “wind”.

The Cavalry had had comparatively few casualties during the past two years. Our party consisted mostly of men who were well used to war, old regular soldiers and volunteers of the first hundred thousand, all good men and true, confident in their officers confident in their sterling NCOs, fully confident in themselves, so it was only natural that they should be calm and steady.

As we walked along the trench from post to post I could feel this strong and quiet confidence in the air, and the Boche could feel it, too, for he was becoming more and more nervous, sending up a profusion of lights and continually opening wild bursts of rapid fire. The bullets smacked into the sandbags of our parapet or went hissing and humming about the wires of Hyde Park, while we, in the deep security of our trench, chuckled at this vain exhibition of fear and fury.

At one post we found all six men standing on the firing step alongside the sentry, staring fixedly into the darkness, which was grotesquely illuminated at frequent intervals by the enemy’s lights. Opposite to this post was, we knew from air photos and from cautious observation through telescope by day, a narrow gap in the enemy’s wire with a distinct track through it, which was clearly used as an exit by their wiring parties and their night patrols. And now in a wide half circle around the exit, with blackened hands and faces, patiently waiting for their prey, lay Hector and his Storm Troops.

The Boche, however, was suspicious; he had heard movement, he had seen sinister shadows; he rained his lights lower and faster and he swept all the ground around with traversing fire. Then we heard the ringing burst of bombs, and, knowing that no Boche would venture out that night, we earnestly wished that the Storm Troops were all safe back again. For half an hour or more we, too, stood watching.

I found myself wondering if Hector would ever make another century at Lord’s; it seemed such a very far cry from this diabolical man-hunting in chaos to the fresh green turf of English June.

Then we continued on our round. Along towards the left things were more quiet. We came upon Jimmie at one of his posts with all hands except the sentry hard at work repairing a traverse that had been blown in during the evening by a minenwerfer bomb.

Further along still, on our extreme left, Eiffel, with all his available men, was out in front, repairing the damage done to his wire by that same evening’s hate. In front of this wiring party, again, lay a covering party, whose duty it was to prevent the wirers being surprised and rushed while unarmed and busy at their work.

We climbed out of the trench and through the first belt of wire to see how they were getting on. This was the first time I had ever been in No Man’s Land, and I felt something of hero as I stood up and looked across to where, a few yards away, I pictured the Germans cowering in their trench.

At this moment a man who was softly tapping in a picket made a bad shot in the dark and hit the fingers of the man holding it for him. The injured man let out a roar of pain and a volley of blasphemy loud enough to awaken the dead. Instantly a machine-gun opposite opened fire.

I sprang into a large mine crater a yard or two away. My right arm sunk up to the shoulder and half my face in a soft woozy substance like a soufflé.

Hastily drawing it out, I began to slide down the side of the crater and clutched wildly in the dark. My hand again slipped along some inches of slime, and then, sinking through it, closed on something hard and stick-like. Grasping this firmly, I checked my descent for a moment, then my support gave way, and I rolled to the bottom of the crater with the lower part of a human leg in my hand.

The stench was so horrible that I was violently sick. I have observed before that war has played strange pranks with the quality of humour. As we walked back along the track that skirted Spade Trench the Skipper laughed immoderately at my unhappу plight, and when we got back to Liberty Hall he woke up Purple and the other two that they might not miss the fun of seeing me covered with this green and nauseating slime that had once been the flesh and blood of a living man.

Lieutenant Colonel Ardern Beaman, DSO

January 1918