The 7th Armoured Brigade arrived at Rangoon on 20th February, and took over from 17th Indian Division north of Pegu two days later.

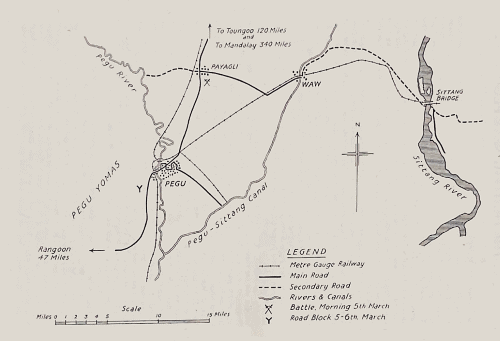

This formation had been very badly mauled at the Sittang Bridge, and urgently required time to reorganize. By the end of February the Japanese had occupied Waw and Payagli, but were not in any great strength, and there was no real threat to Pegu. Pegu, a straggling town with a population of about 20,000, is just over 50 miles north-east of Rangoon.

Communications with Rangoon consist of a two-way tarmac road, which runs for most of the way through thick jungle, and a metre-gauge railway. At Pegu the road and railway turn north to Toungoo and Mandalay, but a branch line goes east to Waw and across the Sittang.

The country north and north-east of Pegu is flat and open, the villages are concealed in thick clumps of trees and the houses in them made of bamboo. The villages are connected with each other and the main road by narrow cart tracks unsuitable for MT.

The ground at this time of year is dry and hard, but movement across country is greatly restricted by dry water-courses, and the bunds, about eighteen inches high, built every fifty yards to control flooding when the rice is planted.

These bunds were strong enough to stand up to the weight of our Stuart tanks, and we were only able to move across country in bottom gear at about four miles an hour.

The area we fought in is bounded on the east, by the Pegu-Sittang Canal which had foot-bridges only across it, and on the west by the jungle-covered hills of the Pegu Yomas and the Pegu river, both impassable to vehicles.

On the 1st of March, “C” Squadron were detached to guard a vital dump, and we did not see them again for ten days. From the 3rd onwards, the rest of the Regiment took on the role of watching the Japanese in Payagli by day, and, except for patrols, withdrew each night at dusk to harbour near Pegu. At this time we had under command one troop 414 Battery, R.H.A. (Essex Yeomanry) (Noel Shorten) and “A” Company, 1st West Yorks (Stephen Francis). After dark on 5th March, “A” Squadron, (Bill Kevill Davies) was sent back towards Payagli to discourage the Japanese from advancing down the main road, and remained out all night.

The morning of the 6th was misty, and the rest of the force moved up after first light to the positions it had occupied on the previous two days. We should, with our our experience, have known better than to go to the same area three days running, but by day the sun was very strong and the Japanese Air Force active, and there was no other cover available.

We did take the precaution of putting the beaters (West Yorks) through the small clumps near the main road, but visibility was still very poor, and it was decided that “В” Squadron (Gilbert Davies-Gilbert) should go forward to relieve “A” before the mist lifted, taking with them the West Yorks. RHQ meanwhile settled down near the main road in the only bit of shade, and began to brew up. It was now about 8.30 a.m.

Just as breakfast was ready, the mist suddenly lifted, and RHQ was at once shot up from the right flank by anti-tank guns and at least one automatic. Fortunately the enemy’s fire was by no means accurate, for our tanks, scout cars, and one or two trucks, were not dispersed, and the crews were outside their vehicles. We had no H.E. ammunition to take on the anti-tank guns, so a quick and undignified move was made half-a-mile down the road to get out of range. No casualties were suffered, which was a miracle, but a track was broken on the control tank which didn’t help matters, and taking it all round we had been properly bounced! All we knew was that anti-tank and automatic fire was coming from a wood 1,000 yards to the right of the road, which the Japanese must have occupied during the night, obviously with the intention of surprising us when we appeared in the morning. They certainly did!

After a few moments thought, it was decided to bring back “B” Squadron to rejoin RHQ and to attack this party of enemy, who were already under accurate 25 pdr fire from our RHA troop. The plan was that “A” Squadron, with the West Yorks, attacked from the west while “B” Squadron, who had no infantry with them, supported from the south.”A” Squadron, with Michael Stanley-Evan’s troop in the lead, and the West Yorks, went in with great dash, and supported by fire from the RHA and Geoff Palmer’s troop of “B” Squadron over-ran the enemy, captured four-37 mm. anti-tank guns, and killed some forty Japanese. By 10.30 a.m. all was again quiet, and RHQ was back in its old clump of trees. We were quite pleased with ourselves.

The next incident occurred a little after 11 a.m., when “A” Squadron reported three tanks on their right flank. I was on the control set at the time, and refused them permission to attack, as I thought it was probably a troop of “B” Squadron a bit out of position. However, a rapid check-up showed that they must be Japanese, and they were engaged by two troops of “A” Squadron commanded by Michael Stanley-Evans and “Glen” Glendinning.

Though rather like Stuarts in appearance and armed with a 37 mm gun, these tanks had little armour, and within a minute two were burning and the third knocked out. All the crews were killed, and Michael Stanley-Evans later received the MC for his part in the morning’s successes. It is of interest that never again, in any of the Burma campaigns, did Japanese tanks face up to British tanks in the open. We had no casualties in this action, but shortly afterwards “Glen” Glendinning was hit in the head, presumably by a sniper, and died that evening. When a sergeant he had been outstanding as a tank commander in “C” Squadron in the desert, and got his commission just before we left Egypt.

Though we didn’t know it at the time, things were now beginning to go wrong in and around Pegu which was held by 48 Infantry Brigade composed of four weak Gurkha battalions. Japanese infantry, who had infiltrated into the Pegu Yomas, began to attack Pegu from the north-west soon after mid-day, and a party, of unknown strength, cut and blocked the Rangoon road a mile and a half south of Pegu.

Probably the first casualty at this block was Alan Smith, our liaison officer with 7th Armoured Brigade, who was killed when covering the escape of two ammunition lorries. A little later the reconnaissance party of 63 Infantry Brigade, who had just landed, motored into it, and all three commanding officers and the brigade Major were either killed or wounded. We did not hear about these events till some hours later, as we were not in constant wireless touch with 7th Armoured Brigade, who were over 20 miles away, and 48 Brigade were too busy with their own battle to have time to tell us very much.

All was still quiet in our area, and the road to Pegu, which we were patrolling, was clear. At about 5 o’clock we received orders from 7th Armoured Brigade to withdraw into Pegu, before dark, and there come under command of 48 Brigade. I at once went back to contact the Commander, Brigadier Hugh Jones, who I found after some difficulty, as he had left his headquarters and was with one of the battalions. He knew nothing about our orders to withdraw, but agreed it was desirable for us to cross the Pegu river as soon as possible, as the only bridge, though still standing, had been bombed all day, and there were no anti-aircraft guns to protect it. By now a good part of Pegu was on fire and the bridge over the railway couldn’t be used, so many diversions were necessary.

We crawled round the western outskirts of Pegu at a very slow speed, and, after making at least one expedition across country, finally halted, well after dark, in a small clearing surrounded by jungle, and not far from the main Rangoon road. A certain amount of sniping was going on, and Bill Kevill Davies was killed when standing by his tank; he had been a most successful adjutant and later squadron leader, and was a sad loss to the Regiment.

Looking back on it, I think the next few hours were about the most unpleasant I spent in the whole war. We were not under fire, but were in an awkward tactical position as our company of West Yorks had rejoined their Battalion, and we had no orders or information. The whole of Pegu appeared to be on fire, and, for the only time in the campaign, some of our tank crews got jittery, and fired off a lot of ammunition at nothing. However, after sending a troop to shoot up the road block which was about a mile to the south, we eventually moved across the main road and harboured in some open ground east of it.

It was now about 2 a.m. and the Colonel went off to 48 Brigade HQ where a plan was being made to force the road block as soon as it was light. On his return, we learnt that we were to support a frontal attack by the West Yorks and Cameronians, though because of the jungle it wasn’t likely that more than one troop could be used. Once the block was forced, it was to be kept open till all troops in Pegu had been withdrawn.

The rest of the night was reasonably quiet except for a little mortaring, apparently aimed at nothing in particular, and the morning was again very misty. This was most fortunate, as it kept the Japanese Air Force on the ground.

At about 7 a.m. we formed up on the only track leading to the main road, “B” Squadron being in the lead, and, supported by a tremendous bombardment from the Essex Yeomanry, they moved up towards the road block. Things were now somewhat confused, Gurkhas, whom few of us could then distinguish from Burmans or Japanese, were flitting all round us in the mist, and to crown everything, 48 Brigade traffic control arrangements had broken down, and a mass of transport from Pegu drove into the middle of “B” Squadron, threatening to block the road. However, the drivers met their match in the person of Richard Thornton, “B” Squadron’s second in command, and the road was kept clear.

Soon, Geoff Palmer’s troop reached the road block which was formed of burnt-out lorries, and the West Yorks and Cameronians began to clear the jungle on either side. The leading tank (Cpl Barr) attempted to push the lorries aside, but it was brewed up by a sticky bomb, and the crew had to bale out. However, the troop leader and Sgt Davies had another try, and after several anxious minutes made a passage for vehicles, and led the way through.

The infantry meanwhile had driven the Japanese away from the immediate vicinity of the road block, but had suffered severe casualties including Stephen Francis who was badly wounded. This gallant young officer had made a great impression on the Regiment, and was awarded an immediate DSO for his conduct in these operations; he unfortunately died of his wounds.

Apart from some sniping, the road was now open, and the Regiment moved back to the main cross-roads north of Rangoon, suffering a few casualties among “B” vehicle crews on the way. We were followed by the transport of 48 Brigade, most of the infantry withdrawing on foot. With them went our Padre, “Fruity Metcalfe,” who had done magnificent work with the many wounded in and around Pegu, and whom he refused to leave. He was given a well-deserved DSO for what he did.

This was the end of our 24-hours’ fighting near Pegu, and the Regiment had acquitted itself very well. First of all we had inflicted many more casualties than we had suffered, without us 48 Brigade would almost certainly have had to abandon their transport, and, above all, we had set a standard of steadiness and fighting spirit in adversity which we kept up throughout this depressing campaign.

By Colonel R. Younger, DSO, MС