Immediately after the capitulation the British and Australian troops stayed in their units beside the roads.

There were adequate rations available from the remaining stores. The R.A.S.C. operated almost normally and made local purchases of vegetables and bread. The Japanese rook the senior officers into custody for unpleasant questioning, but the main body of troops was left almost unmolested.

Many rumours of Japanese intentions towards us spread around and all of them were optimistic owing to the trusting and considerate treatment we were receiving, and owing to the terms of the capitulation which sounded generous but, of course, were never kept.

Commanding officers reconnoitred sites for building camps in the neighbourhood, as it was expected that we would be left in the same area more or less in peace! Then came orders that we were to march to Batavia, a distance of 200 miles! This would have meant the greatest hardship to white troops unused to the tropics. All preparations were made. The senior officers took energetic steps and the Japanese, considerate apparently as ever, allowed special trains.

We were all allowed to write a long letter home. (This was probably a cunning ruse to trick the unwary into giving away information. It was never sent.) Life on the roadside for the first ten days was free, easy and to many strangely enjoyable after the strain and uncertainty of the previous fortnight. Hopes ran high of considerate treatment.

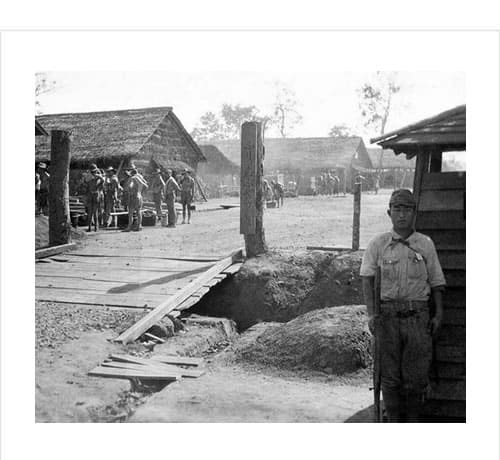

Then came the move. Japanese Divisions are entities of strange individuality and independent thought. Divisions are raised from different towns and departments and so often feel considerable primitive antagonism to each other and apparently, there is often little cooperation between them. The Division then in the Bandoeng area, under which we came, was, on the whole, of a good type (Japanese standards). The Batavia Division, however, was a tough crowd. After a very congested railway journey, we stepped from the guarded train into a new world of unpleasantness. Nothing was in any way as the Bandoeng Japanese had led us to believe.

We arrived at night and were marched to the Native Jail in Batavia. This was a compound surrounded by a high wall with varying types of accommodation built at various dates and designed to hold 700 prisoners. Rather over 2,000 British and Australian officers and men were crowded into it. Of course, both the drainage and water systems were inadequate but to remedy this the Japanese would do nothing. The prisoners were left to their own devices, and some heroic work with the drains was accomplished.

Nevertheless, as could only be expected, dysentery and other diseases broke out. The Japanese provided no drugs, and we were insufficiently supplied from the store we had managed to bring with us. The death toll in Japanese prison camps for us had begun.

Strangely enough, this overcrowded native jail turned out to be in many ways one of the best (or shall one say the least unpleasant) of Japanese prison camps. The food was sufficient and consisted of rice, vegetables and about three ounces of fatty pork every other day. There was never more food in any other camp.

In Java food was, to start with, reasonably adequate. The treatment by the Japanese soldiers was, for the Japanese, not bad. Now and then they would strike a soldier, or beat us up on working parties. The British Camp Commander always put in a protest to the Japanese Commandant on these occasions, and while we were at Glodok beatings were kept within bounds.

The men were sent out to work on Batavia aerodrome filling in bomb craters and levelling the runways that had been blown up by the Dutch. The officers accompanied the men to supervise, and they were often able to intervene, sometimes successfully, when the Japanese guards started to beat up a soldier for not understanding an order, or for “little work.”

When we went out of the prison on these expeditions, those who were lucky enough to have guilders were usually able to buy a few things to eat from the native traders, such as fruit, cake, sandwiches coarse sugar, also native tobacco. Another source of additional food was a contribution of fruit given by Dutch ladies, who were still at large and able to find money. This welcome gift came to the prison once a week and was distributed as equally as possible.

Three courageous airmen attempted an escape from this camp but were caught and shot.

Meanwhile, the smaller fraction of the Squadron had been left in the Bandoeng area with Capt Lancaster as the senior officer. They were certainly lucky for the first two years. The conditions and treatment in the Bandoeng camp compared favourably with that of the Batavia camps. In the later phases of the war, however, conditions became very bad in all camps and there was little to choose between any of them.

In May the Batavia party in the Glodok native jail were moved to another camp close by at Tanjong Priok, near the main harbour. The camp itself covered, by Japanese standards, a fair area. It was surrounded by barbed wire. There was space for paths around the huts and just room for a football field. The absence of a high prison wall gave a sense of space, and we could see green fields and green trees. Living quarters were the old native coolie lines in which the prisoners were crowded even more closely than in the native jail. Sanitary arrangements were either non-existent or inadequate.

Heroic work with the existing drainage system was again performed. Men waded up to their armpits in aged, stinking sewage to clear the drains. Great credit must go to the English doctors for the energetic way in which they tackled the hygiene of the camp. No facilities were provided by the Japanese, no help given, no drugs, no bandages, no material. The Japanese idea of a prisoner-of-war camp was to put the prisoners into an enclosed area, push in just enough food and fuel WIth which to cook it, and then leave them to their own devices.

Life was not too unpleasant in Priok. The Japanese sentries for the most part left us alone. Of course, we had to salute any Japanese whenever we saw one. “Bashings” and “beatings up” were rare, and when they occurred were usually for some offence such as not saluting quickly enough, or the like. There was considerable scope for recreation and entertainment. Football matches took place every evening. The playing standard was very high.

One Regiment in the camp had enlisted nearly the whole of the Cardiff City team. A very high-class band developed which gave enjoyable concerts. and was conducted by Sgt Farmer, 3rd Hussars. Excellent Shakespearean plays were produced in costume-it is amazing what can be done with a native sarong, dressing gowns and paper. Then there was the usual bridge, chess, etc.

The greatest drawbacks to Priok were the tropical heat, the tropical rain (most roofs leaked unmercifully) and the constant fear that dysentery and malaria would get out of hand. In all the camp activities one leading light always seemed to be a 3rd Hussar. Perhaps our superiority was most marked in enticing into the camp, capturing and killing native goats. They were excellent.

From Tanjong Priok about October 1942, parties began to be moved off to other islands, to other camps, and to Japan itself. Treatment was always bad and conditions to those used to Western standards were atrocious. Everything depended on the Japanese camp commander. If he was a reasonable fellow life was possible. If he was a scoundrel life was difficult, to say the least.

Nevertheless, it is astonishing how one accustomed oneself to conditions. 3rd Hussars could be found during 1943, 1944 and 1945 in Java, Sumatra, Borneo, Ambon, Japan and Malaya.

To tell the full story would be impossible. A few extracts from different reports are given below which give a vague impression as to what life was like as a Japanese P.O.W. but living as a Japanese prisoner under Japanese conditions to those used to Western standards is like living on another planet and as difficult to describe.

Extracts

On the 21st of October, I was one of a large draft which was marched to the docks-destination unknown. One has no conception of how many bodies can be pushed into a ship until one has been educated by the Japanese. I could hardly believe my eyes when I saw more and more soldiers disappearing into the holds of the 3,000-ton ship, but in we went. Each hold had a lower and upper wooden platform built into it. The lower one is about one foot off the deck and the upper is halfway between the deck above. There was just enough room to kneel up in a stooping position. There was no room to lie down. The heat was unbelievable and perspiration flowed continuously. We were told that we would be on this ship for the four-day trip to Singapore, so we had great hopes of improved conditions for the longer period of the voyage, which we now understood to be Japan. We were all allowed on the deck only for meals.

On the Singapore docks, we disembarked and experienced for the first time “the glass rod.” The Japanese are punctilious in the red tape and outward ritual of hygiene.

Next, we were put through a disinfectant bath and our clothes were fumigated on a specially equipped ship. Thence, thoroughly cleansed, we were re-embarked into one of the dirtiest ships I have ever been on. The same terrible overcrowding. The same double shelves. The rats and cockroaches were a revelation to man. We lay on our backs and watched them crawl on the deck a foot or two above our heads, big black cockroaches and bigger brown ones in their thousands and thousands-but strangely enough they seldom fell among us.

Eleven hundred British prisoners were crowded into three holds of a decrepit old cargo ship, whilst Japanese troops were in the fourth one. She was called the Singapore Marti, and had not tragedies on a grander scale happened to other prisoners of war in the hands of the Japanese during these years, and had our propaganda needed it. this voyage of the Singapore Maru would have ranked with the story of the Black Hole of Calcutta.

Very soon dysentery began to break out. No concern or consideration was shown by our captors. On board was a quantity of British condensed milk captured at Singapore. Although we begged for a few tins with which to succour the sufferers not one was given. Soon one hold had to be turned into a hospital.

When we had a hundred cases of severe dysentery three tins of milk were provided daily, this magnanimity lasted for about a week, then ceased. One English and three Dutch doctors struggled with the outbreak. They had a little Epsom salts. More and more men were afflicted.

By the time we reached Formosa seven had died, and bere the Japanese permitted a few of the more severe cases to be sent to the hospital ashore, but only one-quarter of the number which had been requested by our doctors. At this step, 700 more Japanese soldiers embarked. An even lower hold was prepared for our men, and down they went into more crowded conditions.

The Japanese, having done less than nothing for the suffering living, were punctilious in their respects for the dead- at any rate to start with. They sympathized. They were sorry. The captain of the ship and the Army officer who lived aloof and never once viewed the conditions in which the prisoners lived, and who was almost unapproachable, donned their swords, picked their way over filthy decks to where our padre, also suffering from the disease, read the funeral services. They saluted as the bodies, wrapped in their soiled blankets, were dropped into the sea, and then returned to their quarters in silence.

If only the Japanese had provided a few drugs and a little milk at the beginning of the outbreak, it might have been kept within bounds. As it was, conditions grew worse and worse. Heroic work was done by the doctors and many orderlies. Volunteers carried stinking buckets up the ladders from the holds and washed blankets until they succumbed. They were brave men.

Exact figures were difficult to obtain whilst we were prisoners, but from the information collected, we estimated that over 350 out of the 1,100 officers and men perished, through neglect and absolute lack of sympathy on the part of our captors during the voyage and the subsequent fortnight after disembarkation.

On the other side of this picture was the heroism of the doctors and orderlies. There was the maintained effort of our senior officer, a Lt Col of the Ordnance Corps, to wring concessions from the Japanese and do what he could for the men. There was the tenderness of a Japanese civilian actor, one of a troupe of male and female artists employed to entertain the Imperial Army who were returning to Japan on the ship. He had been in America and spoke English. He was painfully aware of his countrymen’s neglect, and most of the few concessions we gained were through his intervention.

There was also the good humour and quiet courage on the part of those who survived. The men had spirit enough on the last night to break into the Japanese store rooms, take much of the milk, some tinned meat and fruit, and have a real feast.

For this, the more senior officers were later paraded and harangued by a Japanese lieutenant. We were caged beasts and savages and threatened with punishment when we reached our camps for not controlling our men.

By the autumn of 1944, the position was critically serious. Our official ration ‘per man as non-workers (officers here persistently refused to work, and we were not forced to do so except for one short period in the spring of 1944) became only 380 grams of rice per day. This was subject to a “summer cut” of 10% bringing it down to 350 grams, which, after various individuals had taken a further cut out of it, became, we estimated, about 330 grams or less than a medium-sized teacup of cooked rice three times a day.

Whereas vegetables had been reasonably plentiful, they became very scarce. A typical soup, three times a day, was boiled cucumber. All the little extras which we at first enjoyed, such as soya bean soup every third day, disappeared, and protein was almost non-existent.

Officers lost from 4 to 10 lb. per month regularly. The monthly weigh-day was sure to produce an air of gloom and despondency and not a little fear. By November 1944, nearly all the officers had lost from one-quarter to a third of their normal healthy weight, and one British officer had lost more than half of his.

We could see by the strained look on the faces of the prisoners whom we met that all was not well. Later in the bathhouse, I saw some Dutch soldiers who were thinner than I believed possible for living men and these unfortunates were still going to work down the mine. The camp originally contained only Dutch prisoners. Now, besides approximately 450 Dutch soldiers and sailors there were 46 Americans, 150 British, 11 Australians and 108 British officers. There were very thin officers from Taiwan, fairly thin ones from another Fukuoka camp-these unfortunates had spent two years under the same commandant and a short while previously had rejoiced when he was removed from their camp. Ten days before us they were transferred to Fukuoka “9” only to find him there to greet them. Lastly, there were 46 thin and somewhat weak officers from Zentsuji. The latter were new boys and we all knew how to treat them.

There were many regulations at this camp, but they were published nowhere. Each Japanese guard or N.C.O. interpreted or made up these regulations to suit his whim. We learned the principal ones from the officers who were already there. The others were only learned through a kick on the shins or other vigorous methods of instruction up to being beaten senseless. I was told about many horrible incidents and saw a few others, but what happens to oneself impresses the most vividly, and forbids any doubt as to the authenticity of the outrage.

The most dramatic affair while we were at the camp was the beating up of 90 British officers under the arc lamps in front of [ the Japanese guard room at night. The Wing Commander who came from Zentsuji found himself the senior officer in the camp. He naturally assumed his responsibilities and attempted to interview the Japanese commandant to draw his attention to the abuses going on in the camp and to register protests about food and general conditions.

The Lieutenant would never permit any prisoner to interview him, although it is the prisoner’s recognized right. The Wing Commander, having failed to obtain an interview in the official way of requesting the interpreter, attempted to walk directly into the commandant’s office. He was, however, successfully headed off three times by the corporal in charge. That night, 7th August 1945, all British officers after ” tenko” (Japanese for roll call, were ordered to stay behind. The corporal then harangued us for 45 minutes, while in the background guards with sticks could be seen rolling up their sleeves.

He said British officers were always complaining, the soldier never complained; what right had we to complain, when the British massacred Indians, maltreated natives of the southern legions, and so on?-all the balderdash of Japanese propaganda. For most of this harangue, we were standing with our arms above our heads, receiving a blow or two if our arms sagged. At last, his declamations ceased, and he finished by saying he was going to “beat us until we were dead,” so we were to assume the “on the hands-down” position of a physical training drill. We had formed into two lines with a space between each officer to allow full scope for a swinging stick.

The beating commenced. The corporal led the way down the line. Using both hands on a bamboo pole 10 ft. long and two to three inches thick, he thrashed the buttocks of the prostrate officers. His mate, the guard commander, followed with an ash stake about two inches thick and five feet long as used on the sides of a wagon to stop hay from falling off.

The two guards followed, one with the usual weapon a pick the other with a bamboo an inch or two thick and about five feet long. These two pleased themselves and dealt out their blows wherever the spirit moved them. If you were lucky you got three blows, if unlucky, about a dozen. I was at a place in the line where was a bad to bend owing to the lack of space on the road.

At this corner, all the traffic up and down the line seemed to converge, and I was a little unlucky. The scandalous part about this beating was that it included old men of 60 and patients who should have been in hospital, one of whom was tormented by painful boils. But the Japanese were always unpredictable and there was one officer prisoner who was known by the Japanese corporal to have an unfortunate affliction. Just as the corporal’s bamboo was about to fall on him, he stopped. He called out this officer’s number and made him fall out so that he could escape all punishment.

A Tale from Java

After the Dutch capitulation, there were comparatively few of the Squadron interned in the camp at Bandoeng. I think our peak number was reached in the first six months when there were 16 of us. How and when we all arrived and when we left is impossible to remember nor is it of any particular interest now, so I will confine myself to telling you about some of our activities.

There was a large number of officers and men in the camp but comparatively few were employed in the administration. I commanded the Army troops, Lt Frow had a Squadron and Lt Dallas commanded a Troop and also ran the camp cafe. Lt Chadwick was head gardener and despite “assistance” from the Japanese agricultural expert, affectionately known as “Donald Duck,” the gardens produced an amazing quantity of food. S.S.M. Ellis soon found himself camp R.S.M. but also found time to compere, with great success, some of our camp concerts. It is possible that the Lord Chamberlain would not have passed all his jokes, but as we did not allow any ladies to our shows it was a small point. Sgt Jeffreys acted as S.S.M. to one of the squadrons, LCpl Smith was head salesman in the canteen. LCpl Eastwood worked in the orderly room and LCpl Lever was assistant to the Gardening Officer. From this, you may have gathered that we made our presence felt.

Two officers with 81 other ranks joined a draft of 1,000 men going to Ambon to construct aerodromes. This draft was under the command of Major L. N. Gibson, R.A. Conditions were from the beginning very bad. The accommodation was unsanitary, unhygienic and overcrowded. Food was not sufficient to support even a low standard of health. Work was hard with long hours and no recreation. Medical supplies and facilities were poor. General demoralization and loss of all discipline in my Company of 250 men might have resulted if it had not been for “B” Squadron which gave the other personnel in the Company a lead.

The Squadron suffered 50% casualties. The majority of these were presumed drowned while on sick draft to Java. On the whole “B” Squadron casualties were lower than those of other units which was due largely to its better morale and discipline. Again, “B” Squadron was generally accepted as the best unit in the camp. The N.C.Os. and men worked on the same footing as “white coolies.” Only N.C.Os. of real character and personality retained their position and the respect of the men. Other ranks of the same quality became, in their way, leaders. A new translation of the Regimental motto was often heard “They (the Japanese) will never get us down, Sir.”

Individual 3rd Hussars

A Lieutenant fully demonstrated his character and excellent qualities, although he suffered from gradually failing health and received several beatings from Japanese guards. These beatings took place at the aerodrome working parties where he stood up for his men against the Japanese tyranny. Both in camp and on working parties he handled the men and the Japanese with firm tactfulness. He never complained unduly of the hardships he was enduring. To conclude. he was my right-hand man and a very loyal supporter.

A Corporal was employed on Japanese working parties. He shortened long days for the men by playing up to Japanese guards in a most amusing way. Later he was put in charge of a party of 3rd Hussars

chopping wood in the camp cookhouse and was well thought of by Officer Commanding Cookhouse. In Period 2 he was in charge of the camp “Tea Point.”

This job entailed handling Japanese, Dutchmen and thirsty Englishmen. He showed great personality and fairness. Behind a tough exterior, there was a generous heart. He was “Uncle” to all “B” Squadron. He also took charge of defaulters. Later he was put in charge of the hospital fatigue party and was a popular heartening figure in a dreary place. His last job was burying over 300 men at sea. In hard times he always came to the fore. He was intensely Joyal to me, personally and his stimulating influence was widely felt.

The Squadron returned to Java in various ships and all survivors were in Batavia by Christmas, 1944. The strength was then two officers and (approximately) 40 other ranks. Conditions were not so good as earlier, but after Ambon and especially after the return ship journeys life in Java was comparatively good.

The Squadron was not billeted as a unit during this period but retained its identity and the unit spirit. Early in 1945, approximately 20 3rd Hussars were sent on fresh drafts to Singapore, the remaining 20 were part of an “English Group” of several hundred under my command in “Cycle Camp,” Batavia.

“B” Squadron was still a fighting unit and helped me, as in Ambon, to recover and maintain morale and discipline amongst a group of very “ragged” Ambon survivors of all branches of the Service. 3rd Hussars N.C.Os. were in positions of authority and trust. R.A.F. personnel requested on one occasion that a 3rd Hussar N.C.O. should be placed in charge of them. “B” Squadron never failed to support me in barrack room discussions on policy.

Related topics

- A Short History of The 3rd Hussars

- Timeline: Middle East (Egypt and Libya)

- Timeline: Dutch East Indies – January 1942

- Article: ‘B’ Squadron, 3rd Hussars – The ‘Java’ Squadron

- Article: Arrival in Java – An account of ‘B’ Squadron, 3rd Hussars

- Article: In the hands of the Japanese – An account of ‘B’ Squadron, 3rd Hussars

- Article: Prisoners of War of the Japanese, 1942-45