The following is based on a letter from Major Pat Uniacke, 4th Queen’s Own Hussars, to Major John Graham, 8th King’s Royal Irish Hussars/Queen’s Royal Irish Hussars.

It is felt that in view of the Regiment’s recent operations in that part of the world, readers may find it of interest.

Yes, indeed, I was very much mixed up with the founding of the Royal Harathya Hunt. I first met and became friendly with HRH The Regent when I was serving with the Iraqi Levies from 1938-40, and when I returned after the war to join the British Military Mission to the Iraqi Army, HRH asked me to help him start a pack of hounds. I had been a joint master of the Royal Exodus Hounds, which were based in Habbaniya and run by the Levies, and the Regent often came out to hunt with us and to attend the race meetings. We used to bring the hounds into Baghdad once a year for a week at Christmas time when they were put up at the royal stables. The little King Faisal, then aged about 6, came out with us too on his pony, all dressed up in a red coat and all the trimmings.

Most of the foundation hounds for the Harathiya were brought out from England and some were donated by the Royal Exodus. The hunt flourished for about 10 years until the King, whose coronation had lately taken place, his uncle, the ex-Regent and now Crown Prince, and all the Royal family were murdered on the steps of the Palace, and the hounds, together with Nashmi, the Kennelman, were slaughtered the next day.

I left the Levies to return to the 4th Hussars in the spring of 1941. I feel that my departure may have been hastened by an unfortunate incident when my stallion mounted the Colonel’s mare in front of a parade of some 800 Levies, which he was inspecting. The result, as you may imagine, was spectacular and humiliating!

I arrived in Cairo to find the Regiment was in the closing phase of the Greek Affair and heading for the beaches whence they were soon to be put in the bag. All that remained of the 4th Hussars were encamped, in relative comfort, on the stands of the racecourse at the Gezira Sporting Club in Cairo, where it remained whilst awaiting reinforcement and re-equipment.

So I seized the opportunity to join up with a well known Arabist soldier and traveller, Colonel Gerald de Gaury, who was on loan to the Foreign Office and was about to set off on a special mission to King Ibn Saud, an old friend of his, in Riyadh.

We acquired a 7 seater Dodge Sedan and a Chevrolet pickup truck, a pair of guns for the King and bales of cloth and gold lighters with those fat, impregnated wicks, which you pull out and ignite with a flint, for the lesser mortals. We also drew 500 gold sovereigns and a couple of money belts and started out for Jerusalem, Bagdad and Basra.

I drove the Dodge, a most unsuitable car for such a journey, and my soldier servant, Pascall, looked after the truck and the baggage.

In Basra, we had to buy ourselves complete outfits of Arab clothes, as foreigners were forbidden to enter Saudi Arabia unless suitably attired. Gerald was quite used to this whilst I, bedecked from head to foot in the finest linen, was quite pleased with the result.

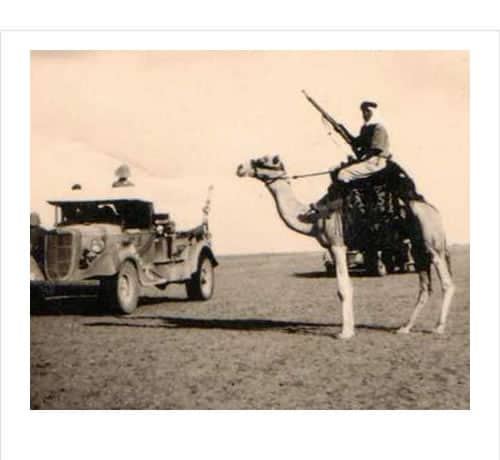

We were met at the frontier by a Lieutenant of the King’s Guard with a platoon of soldiers, four army trucks and an assortment of sheep, and after the customary courtesies, our little convoy moved off.

The next few days were spent mostly in pushing the Dodge out of sand drifts, brewing up frequently and camping each night wherever we happened to be. We had a guide with us, a Bedouin falconer with a bird on his wrist. Gerald tried to light a fire once and the guide said ‘The Colonel has not the technique of the camel dung” We had, of course, brought our own supplies with us and as we settled down each night, the soldiers killed a sheep, built a fire with camel-thorn and dung, when available, and great feasting ensued.

I forget how long it took to get to Riyadh; I think it was 4 days, but it might have been longer. There were, of course, no roads in this country; indeed there were very few in Iraq, and we just followed desert tracks, which sometimes spread out 10 to 15 miles as drivers tried different routes.

We had, of course, long discarded our Arab clothes and were wearing usual desert garb so, as we approached the capital, we got out our robes, shook the sand out of them and prepared to enter this fabled oasis, which lies about 420 miles south of Basra as the crow flies, but considerably more for us.

Many better typewriters than mine have described Ibn Saud’s desert fortress, which had not much changed from the time he came down from Kuwait and captured it with the aid of a dozen men, a great deal of luck and much courage in 1913, I think.

So all I will do is tell you of the sanitary arrangements. The guest wing of the mud-brick palace was 5 or 6 storeys high. We were on the 4th floor. The lavatory arrangements were a hole in the floor of a room immediately above and below a similar room on each floor and ultimately issuing into a cistern which led into the date gardens and supplied excellent manure. On being shown to our quarters by an amiable courtier, he showed us the geography of the house and explained that when we wished to use the hole in the ground, it was advisable to look up at the ceiling. If light (by day) was showing it was safe, if not, get out of the way. We were not told what to do at night time.

The purpose of our mission was to prepare the way for a more formal approach to the King in January 1942, proposing that he should declare war and thus, as keeper of the holy places of Mecca and Medina, unite the Islamic world against Hitler. He received us the day after our arrival. We had already through a chamberlain, presented our gifts and, as is the custom, no mention was made of these.

He was seated in his impressive diwan, surrounded by sons, courtiers, ministers (themselves mostly sons) and fierce-looking soldiers bristling with daggers, swords and other less esoteric weaponry. He was huge, 6’4′ with a figure to match, courteous and welcoming. His eldest son offered us the ritual coffee. He would later become King Saud.

We spent 10 days in Riyadh, Gerald (he was bilingual) having almost daily audiences of the King whilst I amused myself riding and motoring around with some English speaking officers.

My Arabic in those days was not up to delicate diplomatic negotiations. Not that it ever was, I’m afraid to say.

On the day we left, our friend the chamberlain came round to say goodbye on behalf of the King (we had formally done so the day before), and to present us with his gifts. A jewelled dagger and a gold watch with the Saudi Arms on it for me and more munificent offerings for Gerald. The King had been non-committal about joining in the war.

So now we were on our way westward to Jedda, 500 odd miles of desert before descending from the Nejd plateau onto the coastal region of the Hejaz. Thence to Aden via, we hoped, Yemen. The King had given us a letter to the Imam Yahya asking him to grant us passage through his country and, possibly, an audience.

We spent a few days in Jedda and said goodbye to Pascall, who had been the greatest help and a marvellous driver in very difficult conditions but I think he was getting a little lonely in this very odd country, with very odd habits and constraints, and without a word of Arabic; I think it was foolish of me to have brought him along. However, he will remember the trip to the end of his life; not many Hussars’ corporals have set eyes on Ibn Saud! So we said farewell and thank you and, with a wave, he boarded a ferry for the boat to Port Said and 41-I. We then hired a huge, very black Nubian to replace him.

At this time, the Pilgrimage to Mecca had just ended and the Holy Covering or Qiswa was to be cut up and sold to the pilgrims. This enormous black tapestry, embroiled over the door and window openings with verses from the Koran, is made annually in Egypt, ceremoniously sent under escort to Mecca and draped over the Kaaba. This square building houses the Black Stone given, apparently, by Gabriel to Abraham, and is the most sacred shrine of Islam. A Bedouin member of the Legation was going into Mecca, so I asked him to buy me a bit. He came back with a splendid piece, about 3 x 2, lettered in gold, which now hangs dustily on my wall. It cost me £5.

The coastal, rock-strewn track down to Yemen, 450 miles southwards, was even worse than the desert tracks of Nejd, the Arabian Plateau, and the poor old Dodge was looking a bit battered by the time we reached Jisan on the Yemen frontier.

There we were welcomed by the Saudi Emir, who gingerly received the letter for Yahya from Ibn Saud of whom he was mortally afraid. Telegrams were exchanged and the outcome was that the Imam flatly refused to allow British Officers to travel through his neutral country. There was no love lost between Ibn Saud and Yahya which, no doubt, had something to do with it.

More telegrams were exchanged between us and Aden, who eventually suggested that we should make our way to Kameran Island, some 90 miles to the west, whence a routine Blenheim flight would pick us up in due course. And this we did. We sent the two cars back to Jedda to be shipped to Egypt – we didn’t really expect to see either of them again – and chartered a dhow with a crew of four to take us across to Kameran, a little archipelago, which had been used for some years as a quarantine station for ships bringing the pilgrims from India and the Far East to Mecca. It was presided over by an eccentric, elderly and delightful Major called Thompson, who ruled over his little territory with a population of some 300 men, women and children with an amiable ferocity.

We had a cheerful sail across the Red Sea to Kameran, 2 days with a night at anchor, and were received with cordiality by Major Thompson. He took us on the following day on a tour of his domain ending up in the school where we were serenaded by about 30 children with ‘Will you no come back again” in a strong Arabian accent. We stayed on the island for a couple of days and then the Blenheim arrived and flew us down to Aden. There we stayed at Government House for a week until a New Zealand refrigerator ship, with limited but comfortable accommodation, picked us up and landed us in Port Said.

We returned to Riyadh late in January 1942 to receive the British Minister to Saudi Arabia, who drove up a couple of days after us from Jedda, where the British Legation and all other envoys were located, and still are.

On the way, just off the ‘Christian’ road which bypasses Mecca, we came across an airfield with a huge hangar. Inside we saw some ancient aircraft of first world war vintage, left behind, no doubt, by Allenby or Lawrence or some such character, and a beautiful little Messerschmidt, a four-seater, which had been presented to Ibn Saud by Hitler in 1939. It hadn’t been flown since as no one knew how to, nor did anyone seem interested in it.

I had had a pilot’s licence since 1935 and had owned a Puss Moth for a time and I coveted this little thing.

So, when our conference ended, inconclusively, and the British Minister and his entourage had left, Gerald and I went to say our farewells and on the way, I said to Gerald ‘Ask the King if I can have that little aeroplane’ ‘Not me,’ he replied, ‘ask him yourself.’

And in my fractured Arabic and lots of ‘Your Majesty’s, I said what I thought to be appropriate, whilst Gerald winced at my accent, grammar and temerity. However, the King nodded, said a word to a son, who made a note, and that was that. We bowed and backed out of his presence, not an easy manoeuvre when wearing a full-length skirt, and set off back to Jedda and Cairo.

Soon after our return to Egypt, a puzzled sounding first Secretary at the Embassy rang to ask us to call round. On arrival, he said ‘What on earth is this?’ and handed us a telegram addressed to the Ambassador from King Ibn Saud. This read in essence ‘The King understands from Captain Uniacke that the British Forces in Egypt would like his Air Force. He is pleased to offer this and suggests an RAF mission be sent to Jedda to inspect the aircraft and discuss details.’

His air force consisted in the main of 6 Vickers Vimy bombers of about 1916 vintage and my beautiful little Messerschmidt. No one was very pleased with me, as suitable replies and responses had to be made and a couple of senior RAF officers dispatched, reluctantly, to Jedda.

The only person who had the courtesy to thank me was the air vice-marshal who got my Messerschmidt!

A little later, I was again on my way to Jedda, this time in some considerable luxury. General Auchinleck had invited the Emir Mansour. a younger son of Ibn Saud, to Egypt to visit the British Forces and to tour the Western Desert, or the parts we still held.

An opulent ship, Princess Katherine (Master – Captain Barry ) was chartered. She was built for cruising on the great lakes of Canada and had arrived in Suez with her deep freeze full of the most exotic goodies. She had a Royal (Honeymoon) Suite twelve staterooms and a first-class chef. She was, I think, about 6000 tonnes and had a cruising speed of 22 Knots. She also had a huge car deck, empty now, of course.

The party detailed to travel in her to Jedda to greet and escort the Emir to Egypt was led by another Barry, Captain Claud Barry RN, a much-decorated and very jolly ex-submariner and presently Captain of the battleship Queen Elizabeth, which had recently been blown up by limpet mines laid by some intrepid Italians in Alexandria harbour. She was now kept off the bottom by her pumps going night and day, as there was no room for her in the dry dock.

The Germans and Italians were unaware of her condition until the end of the war, thinking her still to be a massive danger to their fleets, should they venture too far out to sea. Paradoxically, this was about the most widely known and best-kept secret of the war.

General Auchinleck hosted a top-level luncheon for the Emir aboard her and the Prince much admired her huge gun turrets which, of course, did not work. Captain Barry brought along his ADC and steward, a naval commander doctor and half a dozen very smart ratings. We also had a press relations officer and a team of press photographers who were to accompany us throughout the tour. I went along as general dogsbody and was to remain with the Emir for the whole of his visit which lasted about a month.

It all went off very well but we breathed a sigh of relief as we anchored off Jedda again on the return voyage. (Claud Barry and his entourage had rejoined the ship for the trip). The Emir disembarked with some ceremony and Captain Barry, his ADC and I went later to the Palace formally to take leave of him.

On our return to the ship, we spotted a launch approaching. The Court Chamberlain arrived to present us with gold daggers and watches and Arab headdresses and cloaks and such like and to tell us that the Prince, having observed our empty car deck, had decided to send 100 sheep as a gift to the British troops in Egypt. These, he said, had just left Mecca, 40 miles away, on the hoof. ‘Good God’, cried both Captains Barry in unison, ‘up the anchor’ and we fled. I never discovered what happened to the sheep. We had a very merry voyage back to Suez.

After this, I did a nine-month stint on attachment to the Spears Mission to the Lebanon.

Named after Sir Edward Louis Spears, a delightful man, one time 8th Hussar, a friend of Churchill and the man who brought de Gaulle out of France in 1940. I found myself to be the Political Officer in the Bekaa Valley, where I had a charming little house in Zahle opposite the Greek Orthodox Archbishop. I complained to him one day that his church bells, ringing at 5.30 in the morning, were disturbing my little dog and waking me up. ‘Not my bells, dear friend’, he said, ‘they are the bells of Archbishop Theosopoulos up the road’.

I returned to 4H in the summer of 1942 and thereafter was mixed up in the to-ing and fro-ing in the desert culminating in Alamein and so on.