Every so often, Regiments have the good fortune to produce – or in our case, to inherit-someone of a legendary character, imposing presence and a range of soldierly qualities admired with affection by all ranks alike.

Such was John Hurst. Probably always destined for the Army, his first encounter with it was however short-lived. A fine upstanding young man, and armed only with a one-way ticket to Scotland, he ran away from school in 1941 to join the Black Watch, only to be sent back south when it was discovered that he was just 15 years old.

Temporarily putting aside further thoughts of Army life, be returned to school and won a scholarship to Steyning Grammar School no doubt more by hard work and determination than academic prowess.

At 18, and by then officially eligible, he enlisted in the Life Guards, earning early promotion to become the youngest ever Corporal of Horse.

One anecdote only will suffice from this period- of which no one could match his own description in the telling – which was when he was on mounted duty at Horseguards and a vandal threw a firework into the sentry box.

His beloved horse Harry had by then composed himself into his usual position of rest until, rudely awakened, he set off down Whitehall at a firm gallop, weaving in and out of traffic with John hanging on by his eyelids. The Mall, the Palace and Hyde Park Corner flew by until Harry and rider made it safely back to Knightsbridge barracks where the explanations began.

Following this – or indeed perhaps because of it- John was selected for officer training at Mons OTCU, and destined for the cavalry. On commissioning it was the Regiment’s great good fortune that he joined the 8th Hussars.

His arrival at Tidworth in 1950 coincided with mobilisation for Korea, and all was activity and bustle, so much so that even this fine-looking new figure suddenly in their midst gained only passing notice. It was only when aboard the troop ship Empire Fowey that they discovered in full who it was they had acquired.

John in a tank proved a wise and popular choice. On arrival in November and appointed to command RHQ Troop, though he had never been at Pusan, and after marrying up with the new Centurion tanks we had seen only briefly earlier, the competition was intense among the squadrons to be the first to go north. In the event, ‘A’ Squadron won but with the attachment, at least for the long rail journey and whatever was to follow immediately thereafter, of RHQ Troop.

Arrival at Pyongyang coincided with the news that the Chinese had entered the war and the whole UN 8th Army was in withdrawal covered by the British 29th Brigade in its sector with ‘A’ Squadron and RHQ Troop (an unlikely first role for the latter, and still less its new commander), in support.

By the spring the British Brigade was back on the 38th Parallel with the famous Injin battle about to take place. John had been appointed to command 4th Troop of ‘C’ Squadron, with Sgt (later RSM) Bill Holberton as his 2IC. The Battle duly commenced on 23 April with countless hordes of Chinese swarming across the river. The Gloucesters and Northumberland Fusiliers bore the brant and it fell to ‘C’ Squadron to advance up a narrow track to attempt to relieve the latter.

A very fierce engagement followed in which, with Holberton’s tank knocked out and a prisoner, the rest of the troop kept the tide of the enemy at bay until their ammunition was exhausted and then, miraculously, managed to withdraw. The Imjin’ was described then as the fiercest battle since World War Two. John’s leadership as part of it was exemplary.

The Regiment’s tour duly ended and it was posted to Luneburg in Germany, where, in 1955, John was appointed Adjutant to the late Lt Col Henry Huth. John’s performance in this role was as ever immaculate in all respects-save one.

Henry was something of a fitness fanatic and all ranks were required to take part in runs in full kit and periodically wearing gas masks. John maintained he wasn’t built for that sort of thing, and Maj Roy Vallance, then RSM, recalls one such occasion when he heard a terrible puffing behind him and John, between gasps and from inside his gas mask, said: RSM, I can’t go on, you will have to take my name. It was then discovered that he still had the stopper in the air intake and how he ever got thus far remains a mystery!

By 1957, and by then married with a young family, John reluctantly decided to leave the Army. Few would have thought however that within him lay all the attributes of a highly successful businessman, but having joined a small company doing something less than well called Southern Industries Coolers Limited, he rose to become managing director and later chairman-retiring in 1986 from what was by then a large and profitable organization.

Thus began what his loving family and many friends knew was his happiest and most fulfilling time, surrounded by his devoted wife Angela and his four sons, three of whom became Irish Hussars and the fourth a Gurkha and of whom he was immensely proud. He was “John Daddy’ to them all. John always said that he wanted to own all his horizons, and at Valley Farm, Battisford all he could see was his.

He loved nature and simple things, and the Suffolk wildlife of the valley were all his friends. A fine talent also was his skill as a craftsman. Much of the beautiful furniture on the farm is of his own making and he fulfilled a lifetime’s ambition to build a complete model steam railway in the garden.

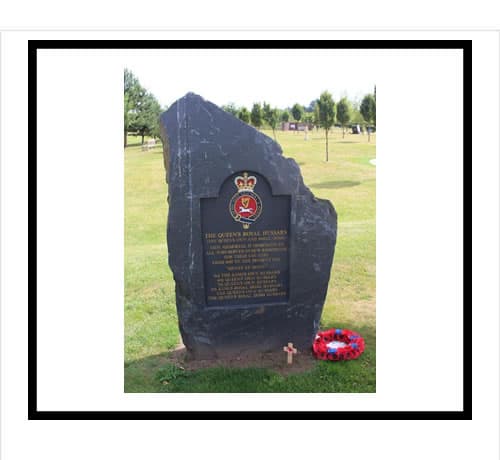

John was an exceptionally generous benefactor to the Regiment he and his family loved so well. The Regimental Association, the Benevolent Fund and the Officers’ Mess all have reason to be grateful for his many gifts and donations.

He died on Remembrance Day 1998 – a fitting coincidence for the family and the host of friends who share his memory.