It was a warm sunny day in June 1943. I was lying on my bed, having just finished my daily big game hunt, and was enjoying one of my own special brand of cigarettes (dried tea leaves in brown paper) when my Jewish companion came waddling into the hut. He had to waddle as he is the only P.O.W. I knew that actually put on weight whilst there; this was due to the fact that he spent most of the daylight hours bargaining items from his Red Cross parcels with the South Africans, and spent most of each night eating his gains.

“Hey! Percy,” says he, “did you know that the ‘Wops’ have disappeared from the sentry boxes and that the gates are open?” “No,” said I, “but what are we waiting for? Let’s go.”

Picking up what remained of my last Red Cross box, I said, “Are you coming?” “Not bloody likely,” he replied, “it’s 800 miles to Naples; I’m waiting until the British get here.” (He was picked up by German troops who overran the camp the following day and taken to Germany. Whether it was due to his race or not, I don’t know, but he never returned.) “Well, Cheerio, I’m off,” and with that, I walked out into the compound and made for the small door next to the Cookhouse, but before I got there I was brought up sharp by a tremendous scream “Where do you think you are going, sergeant?” I turned and there stood a Warrant Officer II whom I had known in Egypt before the war; there he was, no teeth, a long straggly beard, and no hair.

Indeed, this representative of the “Fried Egg” brigade looked a ferocious character. “I’m going home,” said I, “at least I hope so.” “Home? Nonsense,” said he, “the British will be here in 24 hours. We don’t want types like you wandering about all over Italy.” (It took 18 months for the British to get up to this area.) “If you move out of that gate, I’m putting you on a charge.”

You know there’s something about a British W.O. They’d put you on a charge if they could for getting caught in the first place, and there was this pinnacle of British discipline putting me on one for getting out!

So, standing smartly to attention, I said, “Sir, put me on 50 charges after the war if you wish, I’m off; make it 51 and go suck an egg!” With that I went before he got a second wind, otherwise, he might have had ideas of putting me inside, which would have been fatal, as it turned out that he with 6,000 other prisoners were taken over by the Germans the next day and found themselves for the remainder of the duration in Germany, quite a lot of them at Fallingbostel.

After leaving the camp I made off in what I thought was a southern direction, and walked for the rest of the day across fields, avoiding villages and towns until nightfall, when I saw a small farmhouse in the distance. This I made for and knocking on the door, I thought, “Well, this is it; will they arrest me, hand me over, or what?” I was soon to find out. The door opened and a woman stood there, I said, “lo sono un prigineri di guerre io volere un po mangere” and a voice from inside replied, “Come in brother, god damn it I’m a Yankee bum Sit feller, I’ll get some chow.” “Blimey, I thought, have the Yanks got this far?”

They had, but in the form of Bruno, an Italian who forsook Italy for the U.S. some years before, and having returned to soldier for his Duce had now forsaken him for the comfort of his home. But it was in this farmhouse that I was initiated to the delights of Italian dishes; even today, whenever possible, I enjoy them.

After giving me a meal my newfound friend Bruno fixed me up with some straw and put me to bed in the cowshed. I have slept in many beds, sometimes alone, but never before have I had to share my bed with a newborn calf. Being thoroughly tired, I soon went to sleep, and surprisingly enough the calf never resented sharing his bed with me, as he never disturbed me all night.

The following day, Bruno took my old B/D and produced an odd assortment of civvies, kept me in the house all day and at night set off with me to another village, about 10 miles away, to a relative of his. We arrived at this village about 10 p.m., and just as we were about to enter, we heard a shot. “Stay here,” says Bruno, “I’ll go on ahead and find what all this god damn noise is about.” Off he went, and that was the last I was to see of him; after hanging about until dawn, I decided the jerk had run out on me and decided to go on alone. (It turned out that poor old Bruno had been arrested as a deserter on entering the village and taken to Macerata.).

The following day I stayed hidden in the country and was snugly tucked away in a cornfield, when I heard noises of someone approaching rough the corn, so hastily tearing up paper to the required size, I sat and waited, when suddenly out of the corn appeared a girl. As a point of interest, if you have been in a P.O.W. camp for any length of time, all girls look good. I’m sure a cross-eyed, half-breed of Chinese-Indian origin would have half the tongues in the camp hanging out if she were to pass by. But this girl was a wow! Dark eyes, black hair, a good figure; in fact, what I could see of it in a glimpse looked a bit of alright. She said in passable English, “Are you an Englishman,?” “Yes,” said I. “Are you hungry? and would you like to come with me?” What a stupid question for one so pretty! “Lead on, my dear,” says I. She told me that her village of Montepone was free of Germans and Fascists, and her uncle was the Mayor of the village, and all would be well.

The first thing Maria Uommi did was to get me a toothbrush, soap, and a change of clothing. It was rather a nice thing to hear her say that she had heard that all Englishmen cleaned their teeth, hence the brush. I didn’t disillusion her. I stayed with this family for nearly six months; every time that the Italian or German police were going to raid the village, the dear uncle sent his son down to warn me in good time and to get me out of the village. He was no doubt saving his relatives’ skins, and after the raids, Maria would come out to the field to find me and take me back home. You know, after a time I got to looking forward to those raids. It is surprising that after a few weeks I knew most of the villagers and they me, but I felt perfectly safe there; they did not give me away, anyhow.

On Sunday evenings I went with Maria’s father to the house of the village priest who used to lay on wine and food and conduct one of the meatiest card schools I’ve ever been privileged to take part in. As they all staked me at the start, and a couple of times I won with their stakes, I was on the winning wicket the whole time, I never re-turned their stake and they never asked for it.

Being a non-conformist in upbringing anyway, I was, to say the least of it, surprised when the priest started dealing the cards the first time I went, but after that, what scruples I had quickly disappeared with my first win. The padre had a terrific sense of humour; even when the others got me to give my turn, which consisted of swearing madly in Italian, he grinned and said what a stout fellow I was.

This type of life had to cease sometime, as the German and Italian police were having more and more checks of villages and the surrounding countryside looking for the few prisoners left in the area, and one Sunday morning Maria’s father said to me, “You will have to go to church this morning as the Italians are making a further search of the village, and the church is the only place you will be safe in.” So after cleaning myself up, and being briefed on how to conduct myself, off to church I went. All went well until about half an hour from the start when a loud noise was heard at the church door, and about a dozen German soldiers entered. They told the padre to carry on with his service, they intended to search all the people in the church, which they proceeded to do.

I once heard that God moves in a mysterious way, and it looked as if he had brought me to his own house, to learn the error of my ways, and to be returned to camp as a P.O.W. again, but I was mistaking the signs. Maria’s father said to me “come on, but quickly,” and led me up to the communion rail, where we knelt; the padre on seeing me played up, and we took communion; we went back with each party as they had taken, and came up with the next; we went completely around that rail and I must have been served 20 times. As the padre and the supplicants were the only ones not to be searched I was saved again.

I spent the rest of the day hiding up in the belfry and as the troops stayed in the village until nightfall, I realised that for my own sake and for the sake of those who had been so good to me, that I must up sticks and away. I had been told that a partisan group were operating about 2 miles from the village and on the following night I set off to find them. This I managed to do and as one of the Englishmen with them knew me, I was accepted. I only took part in one operation with these stalwart keepers of freedom and here is a description of my one and only engagement.

THE BATTLE

Having, through no choice of my own, found myself in the company of 20 or more bearded, fierce-looking Italians, 3 or 4 Yugoslavs, and a couple of Russians, my one thought was: “It won’t be long now before the British are here and I will be on my way home to Blighty.”

The time was early March 1943, the place a farmhouse about 2 miles from the village of Montepone in the Province of Ascoli in Italy. I had just finished a meal of bread, cheese and apples when a shout went up to the effect that all the company would parade with their arms at once. We were to put in an attack against the dreaded Tedeschi. “Hell!” I thought, “why should this happen to me!” I’d never been a heroic sort and to go into action with a party of nondescripts such as these against the troops of Hitler was little short of suicide. But as the only discipline that existed, was either a good flogging or a bullet, I decided to go along!

The Italian Tenente gave out his battle orders as follows:

“Brothers, this is the chance we have been waiting for, a chance to strike a blow for democracy against these Nazi hordes; we may die in the attempt but our names will go down in history.”

Little did he know that I was working out far better ways to go down in history.

His plan of action was for all the group to hide in the local cemetery and as this was situated at the far end of the one-street village, and the Germans were apparently keeping to the main street, as they emerged out of the village around the bend, they would be met with such withering fire that they would all be annihilated. “Sounds alright,” thought I, until I saw an Italian by the next gravestone to mine filling the barrel of his rifle with bits of nails and the like. These rifles, incidentally, all looked as if they were made in about 1801 or soon after.

Having been well trained in the 8th Hussars, that concealment meant everything in battle, I found a massive monument, about five feet high and four feet across, and decided that my concealment was perfect; not only was the bend in the road completely out of my vision, but I was also unable to see the road at all! I reasoned that the whole German Army could pass through, and I’d still be there, able to head in any direction that would eventually lead to Liverpool and home.

Anyway, after checking my rifle (length of barrel approximately 6 feet) I discovered that the Mills bomb tied to my waist (all part of the build-up) was u/s.! I straightened my red neckerchief, got down even further behind St. Peter, and awaited the arrival of the Nazi hordes.”They are coming through the village,” I heard. “This is it,” I thought, and suddenly the graveyard echoed with noises likened only to those normally heard in the back – yard at home on the 5th November. “Steady the Buffs,” says I, “pop off a shot just to keep my amigos happy.”

This I did, only to find that the stock remained in my hands, and the rest of the bloody thing exploded and fell to pieces at the feet of the good saint. “They are surrendering,” was the cry, “They are giving up without a fight,” said another. “Damn’ good thing, ” says I, and plucking up courage, I peeped around my tombstone to see what stalwart troops had caused this eruption of my normal placid existence and there they stood, all three of them, or should I say, two 40-year-old members of Hitler’s Army and one 10-year-old donkey, they were using in lieu of better transport.

So the battle ended, I suppose today in the village they still talk about the battle of Montepone, when the brave soldiers of freedom smashed the Nazi hordes. It does no harm and undoubtedly boosts their ego somewhat. I like to think that my presence there did some good, if only because I was able to stop the victorious forces from shooting the Tedeschi out of hand.

In fact, they were taken to our farmhouse and became quite useful members of the community. They told me afterwards (I thought it better to keep it to myself) that on the day in question, they had deliberately taken the donkey and were looking for the partisans to give themselves up.

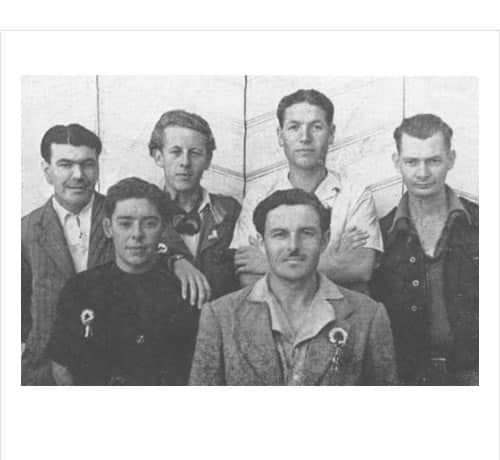

The above is only a personal experience. Attached is a photograph of some of the Englishmen who were active in the partisan movement in Italy. It was taken on the day they reported back to the British Army after spending a year running around Italy. Some of them did some good work, and three of those in the photo were afterwards decorated for what they had done.

Shortly after the battle I left the partisans and made my way to a place called Firmo, from here I hitched a lift by train (without tickets and in the cattle truck) to Foggia, where the American 12th Air Force entertained us royally and flew us to Naples.

We knew we were back among our own people as soon as we passed the sentry on the gate at Naples, “Christ,” says he, “more bleeding prisoners! I suppose you’ve won the bloody war for us? “

After a wonderful journey home on the Queen of Bermuda, I arrived at Liverpool in July 1944, and in September I entered a more rigid and permanent state of a prisoner of war condition by getting married.

The author, Sgt Ferridge, 8th Hussars, is standing on the left in the photo.