So what kind of man was Robert Grant? He was born in Chatteris in Cambridgeshire in June 1816 and worked as a servant. He enlisted at Queen’s Square in London on 9 October 11 aged 19 years and 4 months. He is described as 5′ 8″ tall, of fresh complexion with brown hair and grey eyes.

He served with the 4th Light Dragoons in India for just under 4 years until they returned to England in 1842. During this time his service was not exactly trouble-free. On 27 Sept 1836 he was sentenced to 30 days imprisonment for ‘absence’ and on 30 May 1837 a Detachment Court Martial sentenced him to 20 days solitary confinement. The precise nature of his offences is not recorded.

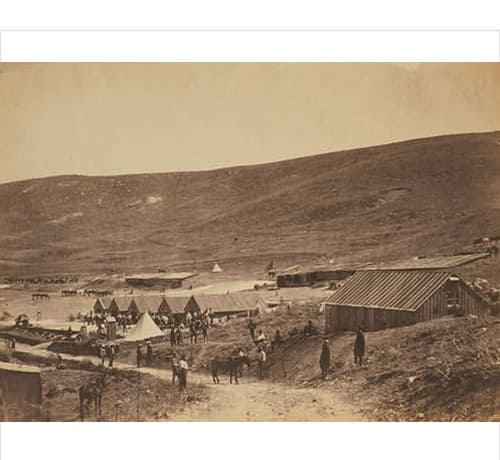

He sailed with the Regiment from Bombay on 13 December 1841, arriving back on 12 March 1842. There are no details of his service immediately after this although it is known that the Regiment went to Ireland in 1846 returning in 1852 and on 12 July 1854 they embarked at Plymouth for the Crimea.

Many accounts exist of the Charge itself but nothing is more graphic than the account Grant gave to a journalist at the 21st Anniversary Banquet held at Alexandra Palace in October 1875. It is worth setting out in full with the kind permission of the London illustrated News Library:

I was a Private in F Troop of the 4th Light Dragoons. Lord George Paget was our Colonel and there was also Captain Portal. I had been out all night with Major Halkett of the 4th visiting outlying pickets. There was a mounted picket of the 17th Lancers on a large hill – I think it was called Canrobert’s Hill – and we also saw the Turkish sentries who were posted on the road. They told Major Halkett that the Russians were in the valley below and he reported the fact during the night to the Brigade-Major. When Halkett came in all the campfires were ordered to be extinguished. The men of the Light Brigade had to turn out early in the morning, or rather stand to the horses. We had not been allowed to undress as on other nights but had been turned out for nothing, and that vexed us.

Were the men anxious to get at the enemy then?

Yes, it was their general talk and feeling. They wished to have the war decided promptly, and their desire was to get to close quarters as soon as possible. Well, the order came about 11 o’clock in the morning, and we were soon off in a trot.

Did the men express any surprise at such an order being given?

No, we had every confidence in our Generals and Officers. We knew they had a better knowledge of what the Russians were doing than we. They had field-glasses and numbers of spies to give them information so that we thought the order was given for the best. In the early part, a peculiar thing occurred. A shot came over a hill and dropped on the neck of a horse belonging to a man named Gowens. The shot cut the horse’s head off as cleanly as if it had been done with a knife. The horse stood for a moment and then dropped. Gowens got on to a spare horse and in a few minutes afterwards, this horse’s head was also shot away. It was the artillery that did it – it played fearful havoc with our horses.

Was not Gowens not hurt?

Not a bit of it. The shot fell eight or nine inches behind the first horse’s ears and it took his head off clean as a whistle.

Were any orders given to halt at any time when you were going down the valley?

We halted once for a short time near the road. The Russians saw us. They did not fire, but they were ready for us. They had man-holes – I mean holes in which a man could stand without being seen. We could only see their heads, at the best and from these holes, they fired on us all the way down; and I remember there was also a little trench flung up, with green boughs. We soon saw the full force of the Russians. We got the Squadron in quarter-distance, and that is the way we charged. All was confusion at the guns. Some of the men got down to cut the traces but each man had to fight for his own life.

They were not I suppose told off for the purpose?

No, but every man did as he liked.

Can you remember any incident of the charge?

Well, something funny took place. I saw two or three old Russians on horses. I don’t know what they looked like. They were quite old men. They appeared to be paralysed and they did not seem pleased and they did not look sorry. They were quiet and still. I put my sword against one of their faces and said What do you want here, you old fools? I would not touch them.

That was chivalry certainly. What made you spare the weaker knights?

They were poor harmless fellows, who as I thought, were obliged to be there. They were not volunteers, but old men who could have given all they had in the world to be somewhere else. They were not the right men in the right place, so I left them and turned my horse to the young and strong, who were using their swords most vigorously. There were too many likelier sort of fellows about to touch without attacking these poor old cripples.

Our officers had revolvers and they did great execution with them. The privates had no revolvers. Those revolvers did great service. In fact, the officers altogether did get a great deal more service than the men, because of the revolvers. Many of the Cossacks got shot foolishly like, for after one discharge they thought it was all over, but the revolver had several barrels. Those Cossacks were all for plunder, and they tried to surround our officers, but they got knocked down with the shots. I gave one man a nick between his shako and the top of his jacket. He fell, but I do not know whether I killed him. I can’t remember whether he sang out at all, but he did not trouble me again.

Did you see the Lancers (Polish) about whom so much has been said?

I thought they were our Lancers and I got close to them, but they did not stir. They were great cowards and I heard from our prisoners afterwards that they were disbanded. I was actually going round to form on their flank, but devil a one stirred. I had passed some distance when my horse was shot under me. He was hit in the hindquarter. His belly was cut open and his legs were broken. The shot came from a cannon that had a low sweep, and it struck him in the thick of the thigh. My leg was covered in blood – I could not get free from him for some time.

Captain Portal passed and he said to me D— you, get up, never mind your horse. But I replied I can’t for he is lying on me A private named Macgregor of our Regiment came to my assistance. He asked me to get behind him on his horse, but I was not able, as I could not use my leg. I managed to find my way by some mystery at last to the camp and they pretty well all got home. I made the forty-fifth man of our troop who returned and we went out with 135 men.*

It was worse coming back than going, for we did not know where we were. Lord George Paget thanked us all as we reformed on the hill, saying Well, my brave fellows, I am thankful to see you back again. The Russians were afraid to follow us up the hill, for if they had they would have had it hot from our artillery. who were ready for them.

*The Regimental History says that of the 118 who set off for the guns. 62 returned. Major Halkett was among those killed.

The Regiment returned from the Crimea in 1856 and in 1860 went to Ireland from where the now Sergeant Grant was discharged at his own request on 16 October of that year having completed 24 years and 308 days service. He was aged 44 years 3 months. His Conduct was recorded as A good soldier with 5 Good Conduct badges. The Long Service and Good Conduct Medal was confined in January 1861 and with it a gratuity of £5. His pension of 1s 1d per day on discharge was increased to 1s 7d on 1 June 1861 for Gallantry on the Danube!

He returned to his birthplace of Chatteris but in December 1869 he was admitted to the Royal Hospital Chelsea at the comparatively early age of 53. He regularly attended reunions and was a Member of the Balaclava Commemoration Society.

He remained an In-Pensioner for 32 years until his death on 15 January 1901 aged 84. He was buried in Grave No 14435 Plot K54 at Brookwood Cemetery 4 days later. His grave has no marker as In-Pensioners from Chelsea were graded as Second Class Burials – no more inappropriate classification for him and his like can be imagined.

Captain RSJ Wallington