On 30 November 1914, 4498 Squadron Sergeant-Major William ‘Billy’ Reeves, who was a regular soldier of the 7th (Queen’s Own) Hussars attached to the 1/1st North Somerset Yeomanry as the Permanent Staff Instructor to ‘A’ Squadron, wrote a long account of his experiences since arriving in France at the beginning of the month:

‘As you know, when we left England there was some idea that we should not be sent up into the fighting line, but employed on more peaceful duties. This idea was very quickly dispelled, for we had only been out a few days when we were sent up into the very thickest part of the fighting. I am not allowed to tell you in this letter exactly where we were, but as I have already seen it mentioned in a Bath paper it is unnecessary.

Our first real introduction to the fighting was when a real ‘Jack Johnson’ shell, which I believe weighs something like 800 lbs., came screaming over our heads and struck the ground within 30 yards, smothering half the squadron with mud and dirt, and causing large stones to fly in all directions. We then tied our horses up in a field, which appeared to have been a favourite spot for the German artillery as there were five great holes in this particular field where the shells had dropped. We had not been there very long before they began to drop around us again, and one actually came so close that several of the men were knocked down by the force of the explosion. I think it was then that Trooper (sic) Yerbury received his injury.

That evening we formed up to go into the trenches, and a few moments after moving off a shell struck the exact spot on which the regiment had stood in mass, just a few minutes too late to wipe out half the regiment. We marched about four miles up to the trenches, floundering through mud up to our knees, and when we arrived we were told we were not required, so we marched back. I think it was on the way back that S.S.M. Cox fell out, for he was not with us when we got back to —– (Ypres).

We all turned in in a building for the night, but it was obvious the Germans had got wind we were there, for their shells continued to drop the whole night, and one eventually dropped near enough the officers’ quarters to smash every window in the place. Then we saddled up and cleared, and it seemed an act of Providence that, with the exception of Yerbury and one man from ‘B’ Squadron slightly injured, we had no other casualties, either to horses or men.

The following night we were ordered to take our turn of 48 hours’ trench duty, and on our arrival there three troops of ‘A’ Squadron were sent into the firing or main trenches, and the remaining troop and the other two squadrons were put in the supporting and reserve trenches. The night was bitterly cold, but with the exception of an occasional outburst of rifle fire passed fairly quietly. During the morning and well into the afternoon we were subjected to a most terrific shell fire from the German artillery, and it is utterly impossible to try and describe the helpless feeling one has when sitting in a trench and having all sorts of shells banging and bursting overhead. I think we must have had quite 200 shells at us during the afternoon, and when I tell you that not a single man in the trench was hit it will seem hardly credible.

Poor Bristow and several other men had been sent to a ‘dug out’ behind the trench as we were thought to be rather crowded, and by a most unfortunate coincidence these were the only men to suffer – a shell dropping among them, killing Bristow and wounding Lce.-Corpl. Dennis, Ptes. Long and Riddle (sic) – Long has since died.

We were due to be relieved by ‘B’ Squadron about 6.30 p.m. About 6 the Germans made a strong attack on our trenches, but we saw them coming, and gave them something to go on with, but it took us over an hour to finally push them back and for us to get relieved. ‘B’ Squadron and the remaining troop of ‘A’ Squadron then took up the position in the main trench, while the other three troops of ‘A’ Squadron went back to the reserve trench.

During the night things were fairly quiet, but about 10.30 the next morning the German guns began to shell our trenches for all they were worth. This went on for perhaps a couple of hours, and soon after mid-day their infantry attack commenced. They came along in hundreds and our fellows simply knocked them over in dozens and again and again we drove them back. After a time, word was sent back for the remainder of ‘A’ to go up in support, which we did, and we were then able to hold them and finally drive them back.

Our losses were heavy, but we have the satisfaction of knowing that we bore the brunt of the attack, and the finest troops in the world could not have stood their ground or been steadier under fire. There was never any suspicion of them giving way, and all the stories about our boys not being fit for service have been dispelled.

We have the satisfaction of knowing we did our duty, and, if called upon, will do it again.’

William Reeves had attested for the Hussars of the Line on 2 January 1899. Born at Chelsea, at the time of his enlistment he was aged 18 years and two months and was employed as a clerk. Reeves was also serving as a member of the 2nd Middlesex Rifle Volunteers.

Posted to the 7th (Queen’s Own) Hussars at Norwich, he was appointed Lance-Corporal on 1 May 1900 and was awarded his first Good Conduct Badge on 2 January 1901. Promoted to Corporal on 30 November 1901, he embarked the same day for active service in South Africa, for which he later received the Queen’s South Africa Medal with clasps for Cape Colony, Orange Free State, South Africa 1901 and South Africa 1902. Reeves remained in South Africa after the conclusion of hostilities and was promoted to Sergeant on 13 April 1903.

While stationed at Potchefstroom in 1905, Reeves passed his 1st Class Army Certificate of Education on 26 September and married Sarah Ann James on 12 October. He also extended his engagement to complete 12 years with the Colours on 11 December. At the end of the year the 7th Hussars were posted to England, and his wife gave birth to their son, James William, at Norwich on 27 October 1906.

Reeves attended several courses while at home, passing his certificate as an assistant instructor in cavalry pioneer duties at Chatham on 13 November 1907, qualifying as a musketry instructor at Hythe on 31 March 1908 and also his assistant instructor’s certificate in signalling at Aldershot. He re-engaged to complete 21 years’ service while stationed at Aldershot on 17 February 1910 and was promoted to Squadron Quartermaster-Sergeant on 19 May.

The 7th Hussars were posted to India in October 1911, and while stationed at Bangalore his wife gave birth to their second child, Kathleen Mahala, on 27 October 1912. The following year was a tragic one for the Reeves family as both his wife Sarah and son James died of diphtheria. At the end of 1913, Reeves and his daughter were sent home to England and he was posted to Bath on being attached to the North Somerset Yeomanry.

For his actions while serving dismounted at Zillebeke on 13 February 1915, Reeves was awarded the Distinguished Conduct Medal.

News of the award was printed in The Western Daily Press on 9 March:

D.C.M. FOR SOMERSET SERGEANT MAJOR.

‘For his gallantry in the trenches last month, Staff-Sergt. Reeves, of the Bath Squadron, North Somerset Yeomanry, has been awarded the Distinguished Conduct Medal, and personally complimented by Brigadier-General (sic – Major-General) Byng. The act which won him the distinction was thus described in a letter from Corpl. Tom Pyatt to his mother, in Bath, a fortnight ago:

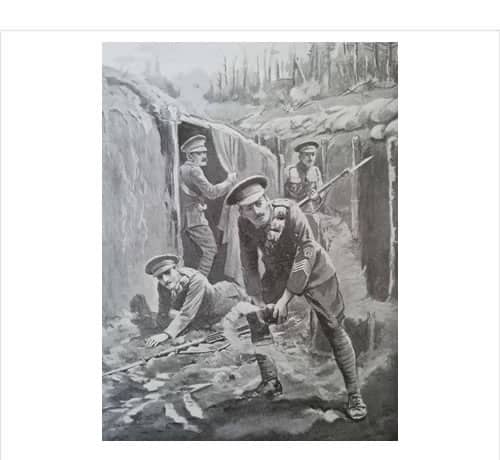

‘In places the German trenches were only 30 yards away, so we had to keep a good look-out. Luckily our casualties were small. I had a miraculous escape. A German bomb fell in the trench not a foot from me. I did not see it coming, and nothing could have saved me or Dick Moody and the other fellows with us, had not Sergt-Major Reeves made a dash for it. He picked it up, pulled out the fuse, and threw it out of the trench. It was the bravest thing I have ever seen.’

The citation for the award was published in the London Gazette on 1 April 1915:

‘For gallant conduct at Zillebeke on 13th February, 1915, when he picked up a bomb, the fuse still burning, and threw it out of his trench. This prompt action undoubtedly saved the lives of three of his comrades.’

Squadron Sergeant-Major Reeves D.C.M. was evacuated to England on 24 June 1915 after breaking his collar bone and thigh, but returned to France on 8 September. While recovering from his injuries, it was announced in The London Gazette on 24 August that he had also been awarded the Russian Cross of St George, (3rd Class). Reeves was promoted to Warrant Officer Class II on 25 September 1915 and was appointed as Acting Regimental Sergeant-Major to the 1/1st North Somerset Yeomanry on the same day, just before they went into action, again dismounted, at Loos.

He was commissioned in the Royal Field Artillery on 24 October 1916 and initially posted to the Base Details at Le Havre before joining 4th “B” Reserve Brigade at Boyton in Wiltshire. He subsequently returned to the front and in 1917 was awarded the Military Cross. News of the award was published in The West London Press on 7 December:

DISTINCTION WON BY A CHELSEA OFFICER.

The many Chelsea friends of Lieut. W. (Billy) Reeves D.C.M., R.F.A., will be pleased to know that an immediate award of the Military Cross was made to him on September 19. We understand that he was again recommended the same day by the infantry. In addition he received a card of appreciation from the G.O.C. (of) his division for his gallantry. Lieut. Reeves was in the middle of the fighting and went over the top with the infantry on both days. It was in February 1915 that he won the D.C.M. and the Order of St George of Russia (3rd class), when he saved the lives of several of his comrades. He went to France early in November 1914, on the permanent staff of the North Somerset Yeomanry, and remained with them until 1916, when he was given a permanent commission in the R.F.A. He is a native of Chelsea and is the son of the late Mr and Mrs G. Reeves, for many years residents of Sydney-street and Lincoln-street. He was educated at Marlborough-road school, and joined the 7th Hussars in 1898 (sic). He will have completed 20 years’ service in January next.’

Reeves attained the rank of Captain by the end of the war, and was issued with the clasp and roses for his 1914 Star on 23 September 1925, by which time he was living at 1 Tyne Road in the Bishopston district of Bristol.

Captain William Reeves D.C.M., M.C. frequently attended regimental dinners and reunions of North Somerset Yeomanry Old Comrades’ Association after the war. By the 1930s he had moved to Newcastle-upon-Tyne, but travelled down to Somerset for the Old Comrades’ Dinner held on 13 May 1933 at Fortt’s Restaurant in Bath, remarking that: ‘some of the finest men he knew were in the North Somerset Yeomanry, and he really loved them.’

Author: Mr Andrew Thornton.

Originally posted in March 2019 on The Old Contemptibles – Men of the British Expeditionary Force 1914 – https://www.facebook.com/OldContemptibles1914

The illustration of Squadron Sergeant-Major Reeves performing the acts for which he was later awarded the Distinguished Conduct Medal was published in Volume 2 of ‘Deeds that Thrill the Empire.’