It was on October 28th. 1940 that the Albanian and Italian forces invaded Greece. The Greek Government, having trained its young men by conscription over many years, called the nation to arms and, by Nov. 8th., halted the invaders and captured 5,000 Italian prisoners.

What a fantastic feat by soldiers armed with old fashioned W.W.1. equipment, Mules carrying mountain Artillery and much of their supplies were moved by Bullock Carts travelling less than 20 miles a day. Just six days later the Greek Army pushed the invaders back over the border, driving on to capture Koritsa and the port of Sarande, In six weeks the Greeks had defeated the Italian 1X Army and occupied a large area of Albania.

What were we doing whilst all this was going on ?. Well, our Air Force was involved with a limited force but our Army was up to its neck fighting in the desert Wavell campaign. Our first links with the Greek Campaign were forged in April 1939 when Great Britain guaranteed the independence of Greece but, though much was said, little or nothing was done.

It was the failure of Italy and Albania to occupy Greece that boosted the morale of unoccupied Bulkan States and prompted Hitler to take over the campaign. He assembled six divisions in Romania, originally earmarked for the invasion of Russia, and invaded Bulgaria. This movement compelled the British Government to honour its commitment to Greece and, on Feb. 24th, the cabinet agreed to send a military force.

“I was in the Tank, a Gunner/Wireless Operator in a Mark VIB light tank. We first came into contact with the Germans in Northern Greece, when we were ordered to advance.

I was manning the machine gun (the only armament on a Mark VIB) when we were hit, taking a round right on the machine gun. I was blown back into the turret and knocked out. When I came round, the front of my tunic was drenched and I thought, ‘I’ve been hit, I’m covered in blood’…but then I looked down and saw that it was only the cooling water from the gun.

We baled out and ran. As I was running, I dropped my .45 revolver and stopped to pick it up. All around where it lay the dust was being thrown up by machine-gun bullets. I decided to leave the revolver where it was.”

Fred Coulter (4th Queen’s Own Hussars)

About two weeks later a contingent of our armed forces landed at the ports of Pireas and Volos and moved north to the Yugoslav border. Available for immediate dispatch were two Infantry divisions, Australian and New Zealand, two medium Artillery Regiments with A/A units and an Armoured Brigade consisting of the 4th Hussars and 3 RTR. The role of this force was to support the Greek Army already committed in battle.

The 3rd tanks were equipped with fifty-two medium A10 worn out Tanks which had chased the Italian forces out of Egypt and across Ceranaica. It is interesting to note that the spares dispatched with the regiment were for A13 Crusader Tanks which were handed over to 5 RTR in exchange for the A10s.

The 4th Hussars had fifty-two MK6 Light Tanks armed with two machine guns. Massed on the other side of the border were five German Divisions including four hundred and fifty Medium and Light Tanks and a vast armada of aircraft.

The planned strategy was based on whether or not the Yugoslav Army offered effective resistance. If they fought the Germans then we would cross the frontier to their assistance but, in the event of their collapse, the long northern frontier and the port of Salonica would have to be abandoned. A more compact defensive position, based on Mount Olympus in the east and running along the deep defile of the Aliakmon River to the Albanian Mountains in the west, would be adopted.

Churchill believed that, if we could hold this line, it would be a suitable jumping-off point to attack the soft underbelly of Europe at some future date. A fantastic plan, if only we had something to defend it with. There were no illusions among commanders on the ground of a successful defeat of the German Army in Greece.

It was accepted that, by honouring our pledge to the Greek Government, our positive action would influence the attitude of other, as yet, uncommitted nations. Well, there was no effective resistance by the Yugoslav Army, not because they had no stomach for a fight, but were denied the opportunity by their own government. Hitler had issued a threat and the government signed a pact.

A revolution followed and the German Army moved in to quell it with Belgrade being heavily bombed as an act of punishment.

We, the Armoured Brigade, were dispersed in the low ground between Florina and Edessa, covering the road through the mountains at the Monastir Gap. Much of the area east of the position was bogland presenting a barrier to heavy vehicles and, with worn-out tracks and no spares, a severe restriction to Tank movement.

It was planned that, when the attack was imminent, infantry and A/Tank Guns would be dispersed on the northern slopes of the pass to detain the enemy as long as possible. Preparations for the defence of the Aliakmon line were in hand and our role in the event of a German invasion would be to inflict as much damage as possible on the enemy, carrying out demolition during a strategic withdrawal.

“Here it was I said good-bye to all and prayed hard as a bomb dropped four yds from myself and Cpl Walker but it failed to explode. However, we went back with many visits from the Stuka’s and the loss of all tanks of the 3rd Tank Regt through mostly track trouble. Our last bit of sport was blowing up the bridge in our area over the River Aliakmon with Capt Kennard, after doing out-post duties, for 24 hours without food and many scares at night…”

SSM Thomas Tasker, RAC (4th Hussars)

The defensive position would be manned by the Infantry Divisions and any remnants that survived the actions of withdrawal, an impossible task for such a meagre force.

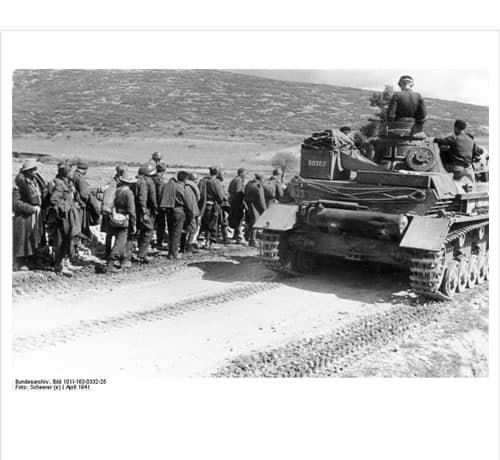

It was calculated that the invasion of Greece from Yugoslavia would start on April 5th and it was on the 6th that the first column of Infantry and Tanks approached the pass, herding before them a host of refugees and Yugoslav Soldiers. Our infantry and A/tank units inflicted heavy casualties on the enemy before withdrawing through the pass and we knew the battle had begun.

Although expected, the onslaught created considerable chaos, mostly the result of inadequate forces and a lack of essential supplies. Decisions of the movement were not strategically planned but imposed by the activities of the enemy and the confusion of countermanded orders. At one stage the tank supply control vehicles were ordered to observe wireless silence without informing the tanks. Contact was never again established until tank crews and drivers met again at Athens Airport.

A composite force of infantry, A/tank guns and artillery, supported by the Armoured. Bde., formed a rearguard to harass the enemy and destroy his forces at every defensible position. This action was remarkably successful in destroying the advanced units pushing south across the plains. By comparison, our casualties were light but the loss of our armoured vehicles was disastrous.

With what was left of the tanks, 3RTR was ordered to defend the road in the Grevena area. The position was overrun and requests to Brigade. for further orders went unheeded, the Brigade. Major had ordered wireless silence before moving to another location, we were left to our own devices without orders. Even a recce. Troop sent out to find Brigade. H.Q. failed to make contact.

Adding to the chaos was the restriction of movement across the front on mountain roads jammed with traffic held up by breakdowns and harassed by enemy aircraft.

We had an Airforce at the beginning of the campaign, Blenheim Bombers and fighters plus a few hurricanes and ancient Gladiators. A total of 80 Aircraft were limited to three or four serviceable airfields, prime targets of the Luftwaffe.

The enemy had 800 German Aircraft on the northern Greek front, 160 Italian aircraft in Albania, and another 160 operating from bases in Italy. Contrary to the feelings of most men on the ground, our pilots did a fantastic job. No praise could be adequately expressed for the Gladiator Pilots who fought the vastly superior M.E.109, preventing them from attacking the troops on the ground, until the last one was shot out of the skies.

Although our A10 Tanks inflicted heavy casualties on the enemy, a very large percentage of our vehicles were abandoned with broken tracks and no means of repair or replacement. The machine guns were removed and mounted in the rear of lorries for continued ground activities and harassment of enemy aircraft. A constant stream of tracer in the air helped to keep the aircraft at a less effective height.

Withdrawal south of the Aliakmon line continued amidst the chaos of blocked roads, burning vehicles, abandoned equipment and columns of sad expressionless refugees and unarmed Greek soldiers. As at Dunkirk, the stigma of defeat and fear showed on every face but, in contrast to Dunkirk, the higher command had given little thought to a probable evacuation. Like much of the planning throughout this campaign, activities were dictated by the enemy.

The Infantry Divisions continued to mount rearguard actions wherever the terrain permitted and without armoured support. The tank crews of the Armd Bde., without tanks were issued with MGs and other infantry equipment and formed up behind the rearguard in the role of anti-Para-troop defence.

Sadly, the transport carrying wireless sets removed from the tanks was blown up and communication was restricted to dispatch riders.

On 22nd. April, the Greek Army capitulated and the mad scramble south to each and every seaport began. All available transport was assembled to transport the troops with the Aussie and NZ. Divisions taking care of their own.

Left to their own devices were the attached personnel of the support services, the majority of which were eventually left stranded on the beach at Kalamata. Troops of 3 RTR were dispersed north of the Corinth canal to defend the bridge until all vehicles had crossed.

Unfortunately, enemy Para-troop activity caused the bridge to be blown before the allocated time, this left many troops stranded north of the canal, it was every man for himself.

A large percentage of the forces were evacuated by the navy from many ports during the hours of darkness but sadly, because of the loss of too many ships bombed by the Luftwaffe, the evacuation was halted before completion.

Later, the considered judgement by the German High Command was that, because of their involvement in the Greek Campaign, they lost the war. It delayed the programmed invasion of Russia by six weeks, forcing the German Army to battle for supremacy during the bitter winter months.