By Colonels Adrian Peck (visited Crete 1999) and Hugh Sandars (visited Crete 1998).

The Battle Honour ‘Crete’ awarded to the 3rd Hussars for the actions of ‘C’ Squadron was the only Battle Honour awarded below-formed unit, as an exception to the regulation that the minimum presence for a Battle Honour is HQ and two sub-units until the 2 troops of the Blues and Royals in the Falklands. Crete was also one of the first major airborne assaults in history.

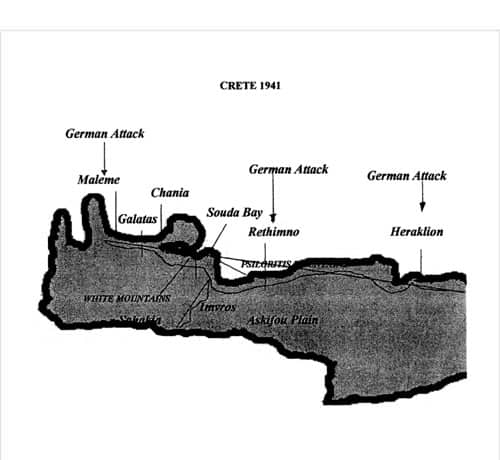

Crete, part of Greece, is an island about 160 miles long from west to east, and about 36 miles wide between north and south. Mountain ranges, with 21 peaks of over 2,000 metres, are dominant along the south. Consequently, harbours on the south coast are few and small; they are also exposed to southern winds of gale force and are of limited use because of the rapid increase in the depth of the shore.

The descent to the north coast is more gradual and there are strips of plain and the best harbours: Souda Bay, the largest in the eastern Aegean, Rethimno and Heraklion. Across the Akrotiri Peninsula from Souda Bay lies Chania, then the capital of Crete.

In 1941 there were two aerodromes, both under construction, Heraklion and Maleme, and a landing strip at Rethimno. They were all on the vulnerable north coast.

Roads were few and easily attacked by air. Even in the coastal plain, movement off tracks and roads is difficult – not good tank country. The weather in May is bright and clear, hot with cold nights.

Nowadays Crete is a popular holiday destination: the countryside is magnificent with many good beaches; the food is excellent; the people are friendly and very pro-British. There are major sites of the earliest civilisation in Europe, and the battlefields are easily made out in a short tour. Every map of Crete has different spellings – modern ones are used in this article.

In early 1941, following failure by the Italians, the Germans attacked Greece and drove the British and Commonwealth forces out, after gallant actions which included those of the 4th Hussars, ending in a very well-conducted evacuation by the Navy. It was decided to defend Crete to stop the Axis progress and to try to retain Souda Bay and the airfields to influence the Aegean.

The forces available were mainly Australians and New Zealanders evacuated from Greece and put under command of General Sir Bernard Freyberg VC DSO. They were short of artillery support and transport, even blankets and spades.

The RAF, under- strength in Egypt, could not spare any significant strength for Crete. The Germans had complete air superiority over the Aegean and Crete, with the result that the Navy could only get up to the north coast of Crete by night.

‘C’ Squadron 3rd Hussars had been withdrawn to refit after the early desert battles, whilst most of the Regiment was in Tobruk. They were sent to reinforce Crete with 16 light tanks which had been hastily repaired in the base workshops.

The tanks were drawn up in a hurry: the radios were not fitted in the tanks, and the water cooling attachments for the .50 and .303 Vickers machine guns, the armament of the Mark VI B, were not available. This led to many stoppages in action later as guns overheated.

The Squadron nearly lost all its tanks, and lost most of its transport and radios, when the freighter was sunk in Souda Bay by Stukas. The only other armour was six heavy I (infantry support) tanks of 7RTR.

The Squadron was led by Major Gilbert Peck (father of Lieutenant Colonel Adrian Peck), later killed in action at El Alamein. Captain Crewdson was Second in Command and the Squadron Sergeant Major was Mr Childs.

Troops were led by Second Lieutenant Roy Farran (later Major DSO MC, an early member of the SAS and author of ‘Winged Dagger’), Lieutenant Clarke, and Lieutenant Petherick. The medical officer was Captain Tom Somerville, who had volunteered to rejoin the army aged over 50, having won an MC and Bar and an OBE in the First World War, and a DSO at Buq Buq in 1940 (where he was originally cited for a VC).

‘C’ Squadron, less 6 tanks detached under Lt David Petherick and sent to Heraklion, came under 4 NZ Brigade, the Force Reserve, and were located near Galatas in the Maleme area.

On 20 May 1941, the German parachute invasion was launched against the airfields at Maleme, Rethimno, Heraklion, the Akritori area, and many other points. They suffered very serious casualties before and on landing.

They were contained at Rethimno and Heraklion, much due to the tanks of Lieutenant Petherick’s troop with machine guns, commanders’ revolvers, and running them over with their tracks as well. All movement and actions took place under constant German air attacks.

General Student, the Commander of the German airborne forces, realising that reinforcement at Rethimno and Heraklion was unlikely to succeed, turned the scale with a final fling of landing the 5th Mountain Division at Maleme regardless of cost. The 22nd NZ Battalion bore the brunt of the assault but was eventually forced to withdraw.

Unfortunately, the command and control systems broke down: the few radios seldom worked and any movement by day attracted close attention from the Luftwaffe. There is a report of one of the tanks ‘retiring down the road hotly pursued by a Messerschmidt 110’. Thus the New Zealand Division failed to counter-attack towards the airfield whilst the Germans were at their most vulnerable.

On 22 May, the New Zealanders did try a counterattack between the coast road and the sea into the Maleme area. Trooper Wilds was recommended for a VC and was awarded a posthumous Mention in Despatches, having died of wounds after he continued to knock out enemy anti-tank guns with one leg almost severed.

By the 23rd, they had to withdraw from the Maleme area, covered by the tanks of Farran and Childs, and the action centred around Galatas, a key ridge after which the Germans would have a clear run down to Souda Bay.

Galatas fell; Crewdson and Farran covered the routes out; and again Roy Farran and his troop led an armed reconnaissance and later counterattack, using two New Zealand infantrymen to replace two wounded crewmen.

In the words of a New Zealander in a later letter, ‘This one pipper bloke was a man of action’. His tank was finally knocked out in the main square of Galatas. As he lay wounded he was given a blanket and water by a local Greek lady. He was captured and evacuated to Greece where on recovery he escaped from the hospital and eventually reached Egypt.

By 26 May it was clear to General Freyberg that Crete could not be held and a withdrawal started by sea from Souda Bay and Heraklion. Lt David Petherick with his detachment, who had played a vital part in neutralising the German attack, destroyed their remaining tanks and were evacuated by the Royal Navy; and underwent severe air attacks before reaching Egypt.

A significant force withdrew towards the south coast to be taken off by the Navy at Sfakia.

‘C’ Squadron again distinguished itself, using the four remaining tanks in supporting the infantry rearguards, particularly in actions on the plateau of Askifou, and in the narrows between the mountains and a gorge at Imvros. These actions allowed a large part of the force to be evacuated by the Navy back to Egypt, with some of those who could not be evacuated taking to the hills with the resistance. A number were evacuated later.

As well as Farran, Captain Crewdson won an MC; and SSM Childs who ‘throughout the whole of the operations showed courage, resource and initiative and set a very fine example…’ an MM. Great credit is also given to Major Peck in New Zealand History.

Captain Somerville stayed to tend the wounded and then also took to the hills with his batman Fred Marlow. He lived for some time with the Resistance and eventually died of pneumonia. He is still remembered with admiration by the Cretans, as is Marlow who just before capture ate Somerville’s will because it mentioned the village that had sheltered them. Despite being taken to Berlin by the Gestapo, Fred Marlow never gave this name.

The present-day visitor can see much of interest. There is a good Naval Museum in Chania with a display of the Naval aspects of the Crete campaign.

The battlefield features, though much built over, are clear, especially Maleme and Point 107, the defensive feature that dominated it which now is the site of the German cemetery. This was tended until recently by George Psychoundakis, the author of The Cretan Runner. He initially baulked at the job but was told that he had dealt with plenty of Germans when they were alive so he could deal with them when they were dead. He later remarked that there was plenty of room for expansion in the cemetery!

The square in Galatas features a war memorial and a museum. The main pub ‘Uncle John’s’ has a Visitors Book featuring entries by numerous Commonwealth soldiers who had taken part, in revisiting the site.

There is an entry by Roy Farran dated 28 Jan 1989. Then there is an entry on 18 May 1989 by Bob Brice, the New Zealand soldier rescued by his tank from lying wounded in the olive groves; and, dated 15 April 1990, an entry by Bert Hamerton saying that he was the driver of the tank featured in the above entries. Derek Meakin, 3H, visited on 25 May 1994. Behind the pub, armour plates from the tank can still be seen in a garden gateway.

The British War Cemetery at Souda Bay is thought by many to have one of the finest settings of all war cemeteries. It is immaculately kept, with a view down the length of the bay. In it are the graves of Captain Somerville and Corporal Sprunt. Also striking is the number of graves of an ‘Unknown Soldier’: in the words of Rudyard Kipling ‘Known only to God’ – doubtless many Hussars among them. Their names are recorded on a wall in the Commonwealth War Graves Cemetery in Athens.

Unfortunately, the New Zealand and 3rd Hussars dead were buried in mass graves at the time of the battle. They could not be identified when reinterred at the end of the War. The UK/Crete Veterans Association still runs pilgrimages to Crete to coincide with the Greek celebration of the Battle of Crete.

From the military point of view, there are parallels with the Falklands, in the mirror image, with us defending rather than attacking. The fleet having to remain away from the enemy side of the island, the ‘bomb alley’ anchorage, the infantry with little transport and short of support weapons, the value of a few light tanks, the key role of air superiority.

Even in these circumstances, the German airborne forces took such casualties, and it was such a close-run thing, that they never again used a massed airborne attack.

It may be of interest to speculate on what might have happened if the New Zealand counterattack at Maleme had taken place earlier and had been successful. The Germans would have been defeated and the Allies left in occupation of Crete.

Although the German invasion of Russia took place shortly after the Battle of Crete ended, and the Luftwaffe diverted large resources to support this – would the Allies have sufficient ships, troops and equipment, and air power to divert from the hard-pressed forces in Egypt to garrison the island?

SOURCES ON THE BATTLE

Primary

- The Galloping Third by Hector Bolitho

- Official History of New Zealand in The Second World War – Crete – QOH698 – good coverage.

- Winged Dagger – Roy Farran – QOH Museum. In reprint – Cassell Military Classics, paperback, ISBN 0-304-35084-2.

- 3H Journal 1946. Article based on War Diary was almost certainly written by Major Peck when he got back to the Delta. NB there is a missing section/misprint: events given as 19 May must be about 22-24 as the Germans did not land until 20 May, and the next day covered in the article is 25 May.

- Tercentenary Edition – Roy Farran’s Article.

- Medal Citations.

More Recent

- In The Queen’s Own Hussars Museum, Warwick: cuttings about Capt Somerville (including his RAMC Journal Obituary and the transcript of a BBC broadcast about him); and about Tpr Marlow; and a letter, given to the author of this article by Chryssa Nimolaki, a tourist guide who had been one of the Cretan Runners (Resistance couriers) at the age of 14 with her aunt. She and her parents knew Capt Somerville well. Their translations into Greek of DSO, MC, Dingo, etc can be seen.

- The Cretan Runner – George Psychoundakis autobiography – translated by Patrick Leigh Fermor, who spent the War in occupied Crete as a Resistance leader including the ‘Ill Met by Moonlight’ action of the film, ISBN 0-14027322 -0: one of the sections is trying to get an ill MO in hiding to a doctor but he died en route – this was Tom Somerville.

- The Lost Battle – Crete 1941 – Callum MacDonald Professor of War History

University of Warwick, ISBN 0-333-61675-8 – good coverage of 3H – Chiyssa

Nimolaki is one of the sources/acknowledgements. - Crete – The Battle and the Resistance – Antony Beevor – Penguin.