Operation Granby was the name given to the British military operations during the 1991 Gulf War (United States coalition name Desert Storm) to Liberate Kuwait from The Iraqi Army.

Prior to the war the Queen’s Royal Irish Hussars had just arrived in Fallingbostel as part of the 7th Armoured Brigade (under the command of Brigadier Patrick Cordingley), part of 1st (UK) Armoured Division, and was engaged in training on the Soltau-Lüneburg Training Area known to all as Soltau.

The Commanding Officer, Lieutenant Colonel Arthur Denaro was recovering from a polo accident four weeks earlier when he had broken his skull in four places requiring a metal plate to be inset but was still taking part in the exercise. The other regiments in the Brigade had recently undergone intensive training at BATUS in Canada which the Hussars missed out on having just arrived with the British Army of the Rhine.

Due to additional workloads required by the QRIH troops, to make ready for deployment, other tank regiments were asked to help organise their training.

Troops from the Queen’s Own Hussars helped manage the ranges, providing range instruction and the ‘ammo bashing’ (unpacking the larger tank ammunition in preparation for firing).

Specialist training was provided in desert survival techniques, and a focus was given to NBC training (Nuclear, Biological and Chemical warfare), with an expectation that the Iraqi’s would use their stocks of chemical weapons if coalition forces attacked.

On the 26th October 1990, ‘C’ Squadron of the QRIH was the first to deploy British tanks into the Saudi Arabian desert since Operation Vantage in 1961.

The regiment trooped to the port city of Al Jubayl (scene of a later suspected chemical attack) and awaited the arrival of their 57 Challenger 1 tanks and other equipment.

The first phase; the arrival from mid-October 1990 of the troops to Saudi Arabia, acclimatisation and living inside hot and cramped port hangers under the care of the 1st Marines, themselves uncertain to their British coalition partners capabilities, was a poor experience for the QRIH and not one for which the soldiers were well prepared.

The second phase was their employment; following the arrival of their vehicles from late October, ‘desertising’ equipment not designed or in other cases just unsuitable for desert conditions, and training for their operational role in support of the 1st Marines.

Training for this desert deployment started in earnest with the arrival of the QRIH vehicles. New tactics were now necessary to fight a desert enemy.

In total four months in the desert was spent in preparation and training prior to the start of the ground war. This meant for the already desert trained soldiers of the QRIH there could be no possibility of a roulement of forces, they were there to stay.

The third phase was the arrival of the 4th Armoured Brigade; these additional British reinforcements arrived around December time, which together with the 7th Brigade already in theatre then formed the 1st Armoured Division.

The role of the QRIH was to block and repulse any Iraqi invasion of Saudi Arabia, reinforcing the 1st Marines Division with an armoured brigade.

7th Armoured Brigade’s role to defend Saudi Arabia against a possible Iraqi invasion was not dissimilar to the QRIH previous NATO defence role in northern Europe.

The most potent British military force to deploy since World War Two was sent to the immediate defence of Saudi Arabia.

Challenger 1 tanks were faster, more manoeuvrable, and had improved sighting systems over their accompanying reconnaissance vehicles.

The Combat Vehicle Reconnaissance (Tracked) or CVR(T)s were found to be too slow and not robust enough for travelling at speed over desert terrain. Their Image Intensifying target sighting systems in ideal conditions were effective to 2,000 metres but reduced to 300-500 metres in poorer weather conditions.

Challenger’s Thermal Observation and Gunnery System (TOGS), could pick out targets effective to 10,000 metres in ideal conditions and could also penetrate all weather conditions, smoke and darkness, although reduced again in the heavy rain and sandstorms of the desert battlefield.

The vehicles of the QRIH were not designed nor built with the potential for their deployment outside of 1 (BR) Corps European borders.

After the arrival of everything, the grease had to be cleaned off, sand filters etc. fitted before the regiment made its way by tank transporter into the desert. After which, training for the forthcoming combat began.

Consequently, initial adaptations to vehicles (sand filters etc.) were made at the Al Jubayl dockside as the vehicles arrived by roll-on-roll-off ferry following the end of their three-week sea voyages.

At the start of Operation Granby, the QRIH increased in size from their peacetime strength of 450 to 653 officers and men.

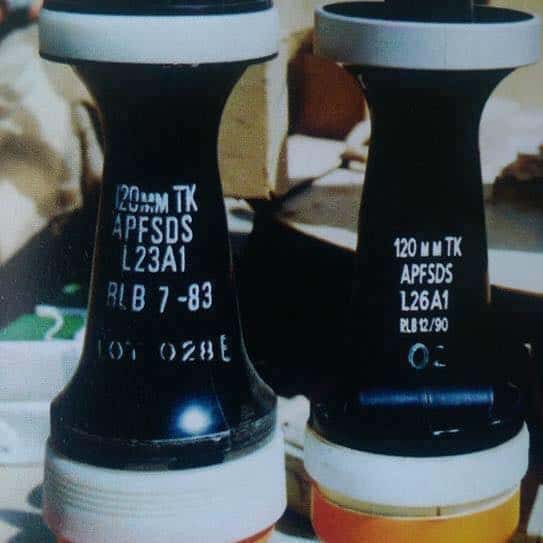

At one point depleted uranium ammunition was issued at the rate of five rounds per tank. During one training day, 14 of the 57 tanks broke down causing serious concerns for Colonel Denaro.

Tasked in September 1990 to defend Saudi Arabia from possible Iraqi invasion and deployed around six weeks later to work alongside the US 1st Marines, the QRIH re-deployed north-west to the Saudi/Iraqi border in January 1991, joining the US VII Corps, becoming part of an enlarged British force forming 1st Armoured Division and with the task of liberating Kuwait.

The Iraqi army knew the regiment was coming. Air bombardment and media interest ensured that they were well warned.

Iraqi Tanks and artillery were dug in across a wide front to provide a warm reception for the allies from the world’s fourth-largest army. Casualty figures were predicted to be as high as 15000 for the allies, even General Schwarzkopf, the allied commander of land forces, estimated 5000.

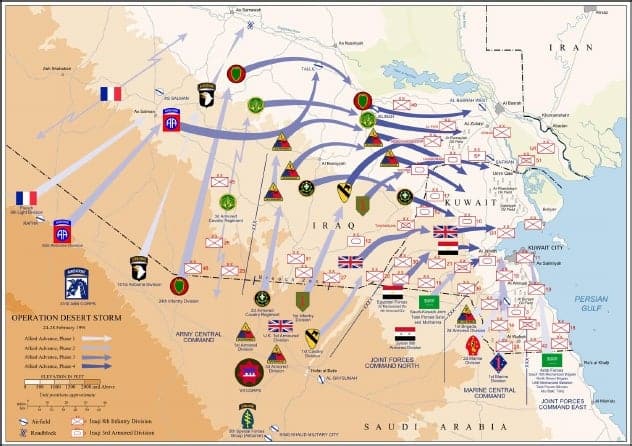

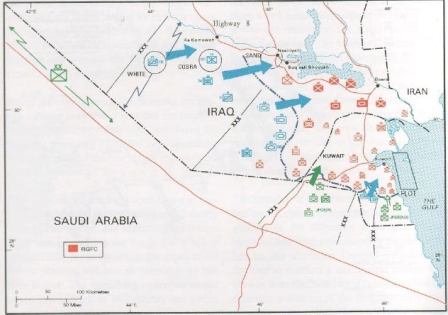

Operation Desert Sabre was the British code name given for the 1st Armoured Division’s attack into Iraq from the 24-28th of February, in order to liberate Kuwait.

Operation Desert Sabre followed the intense allied air bombing campaign of Iraq’s infrastructure and military ground forces, this aerial campaign has been described as providing a ‘contribution to the outcome of the Gulf War greater than in any past conflict’.

The air bombardment started on the 17th of January and lasted for over a month until the beginning of the ground war on the 24th of February.

The role of the QRIH was to act as flank protection for an American led force, shielding the VII Corps by protecting their southern (or right) flank from attack and defeating the enemy’s tactical reserve as the whole formation swung eastwards, advancing towards Kuwait whilst attempting to cut off and destroy the remaining Iraqi Republican Guard Divisions

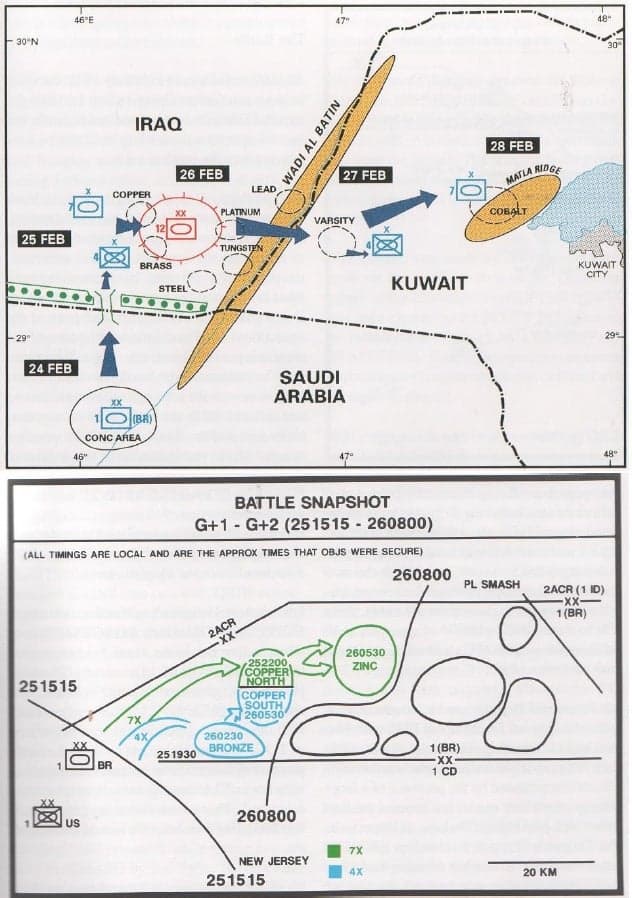

H Hour was at 0300hrs on 24 February 1991: (G Day). The regiment was given the order to cross the start line at 0315hrs.

The QRIH battlegroup consisted of ‘A’, ‘B’, and ‘D’ Squadrons whilst ‘C’ Squadron formed part of the Staffords battlegroup.

Although expecting to depart through the breach from 0830hrs on the morning of the 25th of February, the QRIH did not finally move off until around noon. Advancing American infantry had taken so many Iraqi prisoners, a halt was necessary to evacuate them back through the breach into Saudi Arabia

On the afternoon of the 25th of February, the Challenger 1 tanks of the QRIH advanced into Iraq leading the British force.

The Battle Group was led by Major Maddison’s D Squadron, spearheading the 7th Armoured Brigade’s breakout to the east.

The QRIH had trained as part of a strengthened 1st Armoured Division since December in the knowledge that should it become a ground war, they would be required to attack an enemy known to possess formidable military resources, including chemical and biological weapons.

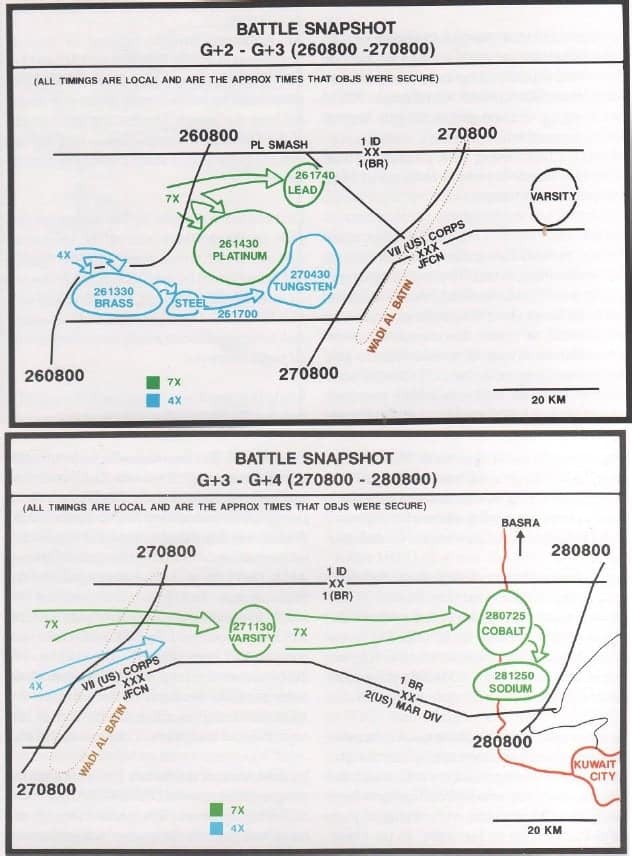

1st Armoured Division’s advance followed an initial attack by VII Corps into Iraq, moving north then swinging eastwards to engage Iraqi forward and armoured reserve divisions

The first contact was not until 1628hrs when an Iraqi trench position was engaged with machine-gun fire before surrendering.

On G+2 reports of a counterattack began to arrive at brigade headquarters. ‘D’ Squadron under Major Toby Madison picked up fourteen thermal image contacts at maximum range and engaged. The battle went on for 90 minutes.

Madison received the Military Cross for his command of the squadron in this action.

The Iraqis were at a severe disadvantage as they had no night vision capability and were out-ranged by the British tanks with their thermal gunnery sights and superior longer-range 120mm tank guns.

Captain Tim Purbrick commanding 4th Troop described firing an Armour Piercing Fin Stabilised Discarding Sabot round at an Iraqi T55 tank, “Our second round entered its glacis plate and exited through the gearbox at the rear, igniting its ammunition and destroying the tank at a range of three thousand six hundred metres.”

4th Troop Leader

‘D’ Squadron

The Queen’s Royal Irish Hussars

On 26 February 1991, a British Army Challenger 1 scored the longest tank-to-tank ‘kill’ in military history, when it destroyed an Iraqi T-55 at a range of 4.7 km (2.9 miles) with an Armour Piercing Fin Stabilised Discarding Sabot (APFSDS) round.

The regiment continued its advance, destroying all in its path until it arrived at the map line “Platinum” at which point a halt was called for sleep for the first time in 48 hours.

Large numbers of prisoners were now surrendering to the regiment.

They were passed rearwards to Regimental sergeant major Johnny Muir’s party who did their best to feed them and keep them safe.

Rations were limited; however as no one had considered that an armoured unit would have to deal with prisoners, often the food supplied was not as nourishing as that provided to the troops.

Items such as oatmeal biscuits, which were effectively leftovers from ration packs, were given along with water.

One Iraqi medical officer expressed concern that he and his fellow prisoners were going to be shot. The RSM assured him that “we are not barbarians”.

After fifteen kilometres of travel recce troop stopped to collect prisoners and were fired up by two U.S. Abrams tanks, wounding Corporal Lynch and Corporal Balmforth, following this up by engaging Command Troop as it passed by.

Following the blue, on blue incident, Brigadier Cordingly ordered all vehicles to fly flags, banners or anything they could lay their hands on to show they were friendly.

He felt the campaign was coming to a close that vehicles from all nationalities were roaming everywhere and that this would lead to more friendly fire incidents. The Irish Hussars did not disappoint.

Union flags and Ulster Banners quickly appeared. Colonel Denaro, a Roman Catholic from Donegal, led the advance into Kuwait from that point onwards with an Ulster flag supplied by his Northern Ireland Protestant crew fluttering from one of his tank’s antennae.

The regiment was then tasked on G+4 to take possession of the Basra to Kuwait City highway to prevent retreating Iraqi forces from escaping. This was done by 0800hrs. The ceasefire was then announced so the regiment went firm and started putting up bivouacs and tents.

As the regiment left the area heading back to Al Jubayl for “de-bombing” the Regimental Sergeant Major was stopped by some civilians who said, “Thank you for giving us back our country”, which seemed to him to be a fitting end to the deployment.

The regiment lost no casualties, no Challenger tanks were disabled or knocked out by enemy fire, and it took part in the destruction of over three hundred Iraqi tanks in a four-day period.

Colonel Denaro’s Challenger 1 tank named “Churchill” is now preserved at The Tank Museum, Bovington with the list of its crew, Lt Col Arthur Denaro, Corporal John Nutt, Corporal Gerry McKenna and Trooper Les Hawkes.