“Prevented by roadblocks from joining the Regiment a few kilometres to their north, the Reconnaissance Troop and ‘C’ Squadron 8th K R I Hussars, made a close laager together at dusk in a large field of roots to the south of Fallingbostel; breaking laager at first light on the 16th April. Somewhere to their east lay Stalag XIb.

The map showed a considerable area covered with regularly grouped blocks of buildings, any one of which might have been the camp. It also showed part of an Autobahn, which, with its mental picture of broad concrete roadways and flyover bridges, should prove an unmistakable landmark.

Nosing its way along sandy tracks that skirted or went through many pinewoods that were the main features of the country, the leading Honey started off slowly. Though there were no signs of any enemy, similar woods had produced quite a few the day before, and the leading tank occasionally raked the edges of the trees and the suspicious hollows or clumps of grass, to discourage any Panzerfaust expert that might be waiting hopefully for us to get within range of his very useful weapon.

The afternoon before, when he had been missed three times, the leading tank commander had confessed to feeling like a goalkeeper in a football match, but this particular sunny morning there was, much to our relief, no sign of them.

A wide clearing confronted us, obviously, man-made, out at right angles through the woods, its sandy surface covered with tufts of grass stretching straight to the right as far as we could see and to the left turning out of sight through two small mountains of earth, this must be the Autobahn, though scarcely what we had expected: the maps had given no hint of this rudimentary stage of construction.

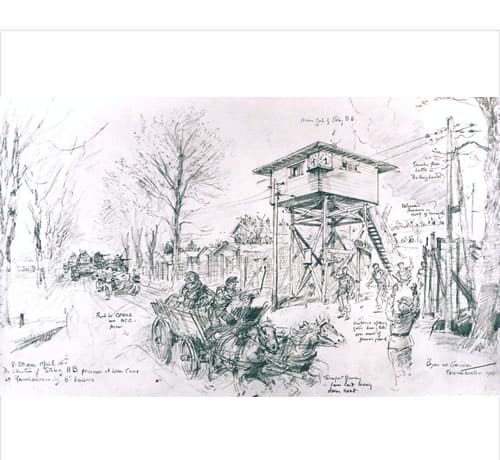

We turned left, came to the huge heaps of earth and halted while the leading commander, Cpl Spencer, dismounted to have a look at what lay around them out of sight. No more woods, but a flat open expanse of grass bounded some thousand yards away by a long uneven line of low buildings, out of which, further to our left rose what looked like half a dozen tall warehouses. Binoculars showed that the main mass of low buildings lay behind a high wire fence – and people. At first, we saw one or two moving about, then made out groups of a dozen, and finally realised that the thickening of the bottom half of the fence was in fact a solid mass of them. At this moment the leading tanks of ‘C’ Squadron approaching on a different route came up behind us, and without waiting to see any more we jumped into our tanks and shot out into the open.

In high spirits, we crossed the grass as quickly as the ground would allow, but as the distance between us and the fence grew less we noticed that the predominant colour of the mass that was now streaming out of the gates towards us was grey, dark grey. At the same moment we saw a French flag – or was it Dutch – which in our excitement we had not noticed before, fluttering behind the main gate.

Our hopes sank; these were not British Prisoners hut but another camp full of all nationalities of Europe that we had come across so many times before. Perhaps there were some British among them, then again perhaps there was no British Camp at all, and the Germans had moved Stalag XIb as they had moved so many others out of the way of the Armies advancing from east and west.

The leading tank came to a stop as the first of the breathless shouting stream of humanity surrounded it, and Cpl Spencer, till clinging to a faint hope, leaned down and yelled

“English Soldaten”? He repeated himself in a moment’s hush, and then a hundred hands pointed to his left, and the clamour of the excited crowd broke out with increased intensity. As he looked around for someone from whom he could get the sense it seemed that every nation was represented, women as well as men, the majority in civilian clothes, with but two things in common, they were all happy and indescribably dirty.

Noticing one persistent man who seemed to have a smattering English he hauled him up onto the tank and asked which way. The fellow pointed, and as the tank moved slowly forward the crowd melted away in front. He glanced over his shoulder and noticed that he was still leading; the Cromwells of ‘C’ Squadron were as uncertain as he had been over the route, but were now following hot on his heels; it was going to be a close thing as to who reached the camp first.

Parallel to the fence, which he had now reached, ran a concrete road and turn left along this, to the accompaniment of cheers from the waving smiling crowd of prisoners and displaced persons that thronged its entire length, he soon passed the tall warehouse that had first been noticed in the distance.

The fellow on the turret pointed excitedly forward but Cpl Spencer could see nothing except a road, tree-lined on both sides, that met ours at right angles. We halted at the junction; to our left, the road went under a stone bridge built to carry the Autobahn, but with no Autobahn to carry looking comically like a piece from a child’s set of toy bricks. A quick glance to the right revealed nothing more than an empty road.

But the guide was tugging at Spencer’s sleeve and jabbering away – and following with our eyes the direction of his pointing arm we saw across the road through a gap between two trees a khaki-clad figure wearing a maroon beret clinging to a wire fence beyond and jumping up and down, obviously shouting his head off, though not a word reached us over the noise of the engines and earphones.

And then all the way down to the right, we could see between the tree trunks more figures racing along the wire. We’d got there, and before the Cromwells, which came up behind just as we moved off down the road giving the glad news over the air. Three or four hundred yards down the road was the main gate to the camp and as we approached the sound of the welcome from the crowd that lined and covered the roofs of the camp buildings grew to a roar that penetrated our earphones above the noise of the engines.

Inside the main gate was an open space packed with British POWs and beyond another wire fence of what looked like an inner enclosure also black with figures.

Quite staggering was the contrast between this scene and that which we had seen at the other camps containing other Prisoners of the Allied Nations. Despite the enthusiasm of the men inside you could see at a glance that there was order and discipline. Camp Military Policemen each with a red armband policed the gates and as the crowd came out to meet us there was no ugly rush but a steady controlled stream that surrounded each tank as it stopped, a stream wearing the headgear of what looked like every unit of the Army.

The Airborne beret predominated – men of D-Day, Arnhem, even the Rhine crossing, who had only been inside a few weeks, but you could pick out the hats, caps, berets and bonnets of a score of others. And under each one was such a look of happiness and thankfulness that made us as happy to be the cause of it. It was a quiet crowd that thronged around us; they had had their cheer, and now when the moment came for words, few words came, mostly they were too moved to speak, men could only grin broadly and clasp your hand as the tears ran down their cheeks.

You couldn’t speak yourselves, only shake as many as possible of the hands stretched towards you and grin back, trying to take it all in and marvel. For these men didn’t look like prisoners, their battle dresses pressed and clean, here and there web belts scrubbed white and brasses gleaming, they might have been off duty in a town at home instead of just walking out from prison wire behind which they had been from anything from five weeks to five years.”

Memories of that scene leaves a picture of a healthy and if not overfed, certainly not starving crowd; of apologetic requests for cigarettes and one man turning green with his first puff, having given up the habit for his three years inside; of the creases in the tartan trews and the shining buttons on the jacket of a CSM in the 51st Highland Division who admitted having marched 500 to 600 kilometers from East Prussia and who didn’t look as if he had been more than 500 or 600 yards from his own front door: of the Camp Medical Officer indignantly denying any cases of Typhus; of the German Commandant and a few of the Camp guards standing apart in a small group watching unmoved the reversal of his role, and handing over his automatic with an offer to show us over the nearby storehouse; scraps of conversation “I’ve been waiting five years for this day” – “Three days ago we expected you” and in contrast “You’ve come too soon, my jacket’s still wet” this from one who had washed his battle dress especially for the occasion; and from one as impressed by our appearance (we hadn’t washed or shaved for nearly 48 hours) as were we by theirs ”You look like real soldiers”: several requests to see a Jeep, which we could not unfortunately produce at that moment; much signing of autographs on both sides and nearly always the first question “What’s your mob?” and finding several members of the Regiment in the camp, captured in the Desert battles, including RSM Hegarty taken at Sidi Rezegh in 1941; and finally, on asking news of their erstwhile captors, being told that they were not long gone and were carrying Panzerfausts.

This was more serious, with all these fellows about, and on asking the MPs to clear the road a bit we got the most startling proof of camp discipline. For at a word from a tall figure wearing an Airborne beret, RSM Lord, ex Coldstream Guards the camp MPs went round and in a very few moments and without a murmur those scores of men, some of whom were tasting freedom for the first time in more than five years, made their way back behind that same barbed wire and netting that to them must have been the symbol of all that was hateful and depressing in their lives.

We left as the vanguard of visitors were arriving, the VIPs and the not so VIPs, the Press and the frankly curious, all wishing to get a first-hand glimpse of the first large predominantly British camp to find itself in the path of the British Army of Liberation.

As we left, taking with us an impression that will never fade, of men whose courage and hope had been kept alive through long years of boredom and privation by their faith in their country, and whose behaviour in their moment of triumph when faith had been rewarded was an example of the highest traditions of the Army to which they belonged.

Troop Leader Tim Pierson 8th KRI Hussars