The 4th of January was the day of the battle — a battle where we had so many casualties.

The battle is virtually forgotten, but in that single action, the 8th King’s Royal Irish Hussars and Royal Ulster Rifles lost more men than 200 men captured or killed.

“I don’t know how the hell people can forget something like that — I feel a bit sad about it,” said Joe Farrell, a former Belfast boxer and veteran of the battle.

In December 1950, having been swept from North Korea by a shock Chinese offensive, defeated UN forces stood at bay in the South. On New Year’s Day, 1951, the Chinese stormed over the border and South Korean forces disintegrated. Britain’s crack 29th Infantry Brigade was thrust into the line near Koyang, 12 miles northwest of Seoul.

Amid blizzards, the brigade dug a shaky line over the hills. On the left flank, reinforced by ten 8th Hussars Cromwell tanks (Cooper Force), stood the RUR. By Jan 3 there was nothing between them and the onrushing Chinese.

Before dawn that day indistinct figures appeared in front of the RUR trenches. A patrol descended into the valley and men on the hills heard a staccato burst . . . then silence. The patrol had blundered into the main assault force and from nowhere the Chinese broke cover and charged. Two RUR platoons were overrun.

Galway native and acting battalion commander Major Tony Blake orchestrated the firepower of tanks, artillery and US jets in an immediate riposte. Second Lieutenant Mervyn McCord was part of a patrol that counter-attacked their old position after a napalm strike.

The men took the ridge without casualties and stood around congratulating themselves until a major arrived, roaring: “This is not a funfair!” Meanwhile, ‘B’ Company prepared to retake the other lost peak.

“We lined them up,” said Captain Robin Charley, a Belfast man who had volunteered for Korea. “That attack went in exactly by the book — just like at the School of Infantry!”

The Ulstermen were ecstatic at having beaten off the previously undefeated Chinese. To their right, the Royal Northumberland Fusiliers had also fought a bloody, but successful battle. Elsewhere, though, the front had buckled. UN forces were falling back. Seoul was to be abandoned.

The RUR would be the last UN unit to withdraw, the US division on its left had already departed.

Their flank exposed, the RUR retreat led down a valley overlooked by the enemy, what the regimental history calls “a death trap.”

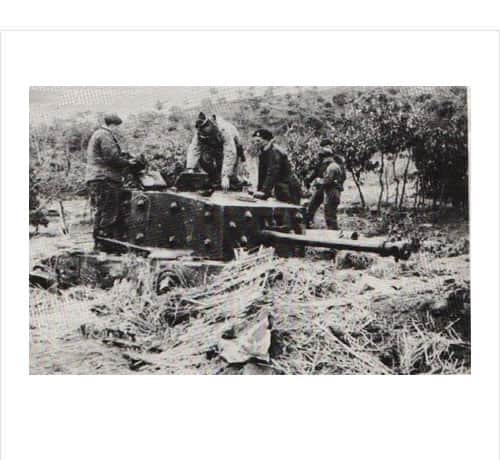

It was a frozen, moonless night and columns of soldiers, with vehicles in the centre, moved stealthily down the steel-hard track. The Cromwells of Cooper Force squeaked along at the rear, slipping and sliding.

Charley, leading with ‘B’ Company, met American trucks at the valley mouth. All was going to plan. Suddenly, fireworks burst overhead: US aircraft-dropped flares. The column was bathed in eerie white light. Men swore under their breaths. Officers hissed into radios, trying, unsuccessfully, to halt the flaring.

The enemy could not fail to spot the retreat. Mortars rocked the valley as streaking tracers raked the column. Then came hundreds of shadowy Chinese pelting down into the valley to seize a village on the southern track, blocking the route.

Lance Corporal Joe Farrell was lying in cover when an enemy squad charged over his back. Grabbing a wounded sergeant, Farrell clambered onto a passing vehicle that ran the gauntlet. Those behind were less lucky.

The tanks were dismembered with pole charges. The last radio signal from Hussar Captain Donald Astley-Cooper, the armoured group’s commander was: “It’s bloody rough!” He was never heard from again.

McCord, in the rearguard, was loading dead onto a carrier when someone said: “You’re missing something.” He looked down and recoiled. The corpse was headless.

Beneath a railway bridge, the Chinese had placed a machine gun. There was only one possible action. McCord and Sergeant Campbell assaulted through the position, knocking out the gun and clearing the route (both were subsequently decorated).

Out of the flashing darkness Support Company Commander Major John Shaw appeared. After yelling at McCord for smoking his pipe in combat, Shaw regrouped the survivors and led a charge through the blazing village and into the hills.

At dawn, Shaw’s men crossed the Han River bridges just before they were blown. The burning capital was abandoned.

Early on January 4 US Forces Korea commander, General Matthew Ridgway had raged at his subordinates for leaving the British.

The RUR lost 157 men captured or killed. The 8th Hussars lost 42 men and 10 tanks. The unit commanders, Blake and Astley-Cooper, were among the dead. All in one night.

Memories of the losses linger. “There was one chap I was at school with, a gunner officer, and when we were ordered to withdraw he had to stay on, and sadly, he was killed,” said Col Charley.